13.2 The Meaning of Monopoly

The De Beers monopoly of South Africa was created in the 1880s by Cecil Rhodes, a British businessman. By 1880 mines in South Africa already dominated the world’s supply of diamonds. There were, however, many mining companies, all competing with each other. During the 1880s Rhodes bought the great majority of those mines and consolidated them into a single company, De Beers. By 1889 De Beers controlled almost all of the world’s diamond production.

A monopolist is a firm that is the only producer of a good that has no close substitutes. An industry controlled by a monopolist is known as a monopoly.

De Beers, in other words, became a monopolist. A producer is a monopolist if it is the sole supplier of a good that has no close substitutes. When a firm is a monopolist, the industry is a monopoly.

Monopoly: Our First Departure from Perfect Competition

As we saw in the Chapter 12 section “Defining Perfect Competition,” the supply and demand model of a market is not universally valid. Instead, it’s a model of perfect competition, which is only one of several different types of market structure. Back in Chapter 12 we learned that a market will be perfectly competitive only if there are many producers, all of whom produce the same good. Monopoly is the most extreme departure from perfect competition.

In practice, true monopolies are hard to find in the modern Canadian economy, partly because of legal obstacles. A contemporary entrepreneur who tried to consolidate all the firms in an industry the way that Rhodes did would soon find himself in court, accused of breaking the Competition Act, Canada’s antitrust law, which is intended to prevent monopolies from emerging. Oligopoly, a market structure in which there is a small number of large producers, is much more common. In fact, most of the goods you buy, from autos to airline tickets, are supplied by oligopolies, which we will examine in detail in Chapter 14.

Monopolies do, however, play an important role in some sectors of the economy, such as pharmaceuticals. Furthermore, our analysis of monopoly will provide a foundation for our later analysis of other departures from perfect competition, such as oligopoly and monopolistic competition.

What Monopolists Do

Why did Rhodes want to consolidate South African diamond producers into a single company? What difference did it make to the world diamond market?

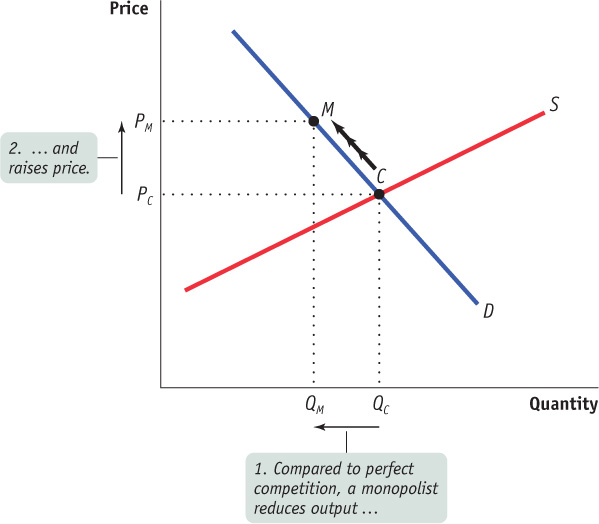

Figure 13-2 offers a preliminary view of the effects of monopoly. It shows an industry in which the supply curve under perfect competition intersects the demand curve at C, leading to the price PC and the output QC.

Suppose that this industry is consolidated into a monopoly. The monopolist moves up the demand curve by reducing quantity supplied to a point like M, at which the quantity produced, QM, is lower and the price, PM, is higher than under perfect competition.

Market power is the ability of a firm to raise prices.

The ability of a monopolist to raise its price above the competitive level by reducing output is known as market power. And market power is what monopoly is all about. A wheat farmer who is one of 10 000 wheat farmers has no market power: he or she must sell wheat at the going market price. Your local water utility company, though, does have market power: it can raise prices and still keep many (though not all) of its customers, because they have nowhere else to go. In short, it’s a monopolist.

The reason a monopolist reduces output and raises price compared to the perfectly competitive industry levels is to increase profit. Cecil Rhodes consolidated the diamond producers into De Beers because he realized that the whole would be worth more than the sum of its parts—

In fact, monopolists are not the only types of firms that possess market power. In the next chapter we will study oligopolists, firms that can have market power as well. Under certain conditions, oligopolists can earn positive economic profits in the long run by restricting output like monopolists do.

But why don’t profits get competed away? What allows monopolists to be monopolists?

Why Do Monopolies Exist?

A monopolist making profits will not go unnoticed by others. (Recall that this is “economic profit,” revenue over and above the opportunity costs of the firm’s resources.) But won’t other firms crash the party, grab a piece of the action, and drive down prices and profits in the long run? For a profitable monopoly to persist, something must keep others from going into the same business; that “something” is known as a barrier to entry. There are five principal types of barriers to entry: control of a scarce resource or input, increasing returns to scale, technological superiority, a network externality, and a government-created barrier to entry.

To earn economic profits, a monopolist must be protected by a barrier to entry—something that prevents other firms from entering the industry.

1. Control of a Scarce Resource or Input A monopolist that controls a resource or input crucial to an industry can prevent other firms from entering its market. Cecil Rhodes created the De Beers monopoly by establishing control over the mines that produced the great bulk of the world’s diamonds.

2. Increasing Returns to Scale Many Canadians have natural gas piped into their homes, for cooking and heating. Invariably, the local gas company is a monopolist. But why don’t rival companies compete to provide gas?

In the early nineteenth century, when the gas industry was just starting up, companies did compete for local customers. But this competition didn’t last long; soon local gas supply became a monopoly in almost every town because of the large fixed costs involved in providing a town with gas lines. The cost of laying gas lines didn’t depend on how much gas a company sold, so a firm with a larger volume of sales had a cost advantage: because it was able to spread the fixed costs over a larger volume, it had lower average total costs than smaller firms.

Local gas supply is an industry in which average total cost falls as output increases. As we learned in Chapter 11, this phenomenon is called increasing returns to scale. There we learned that when average total cost falls as output increases, firms tend to grow larger. In an industry characterized by increasing returns to scale, larger companies are more profitable and drive out smaller ones. For the same reason, established companies have a cost advantage over any potential entrant—a potent barrier to entry. So increasing returns to scale can both give rise to and sustain monopoly. For instance, when wet natural gas was discovered in Alberta’s Turner Valley in 1914, many investors formed “oil companies” in the region. But according to the Calgary City Directory, the number of “oil mining companies” fell from 226 in 1914 to 21 in 1917. The reduction in the number of firms was due partly to the lower than expected flow of liquid gas from wells and partly to the relatively high cost of extraction.

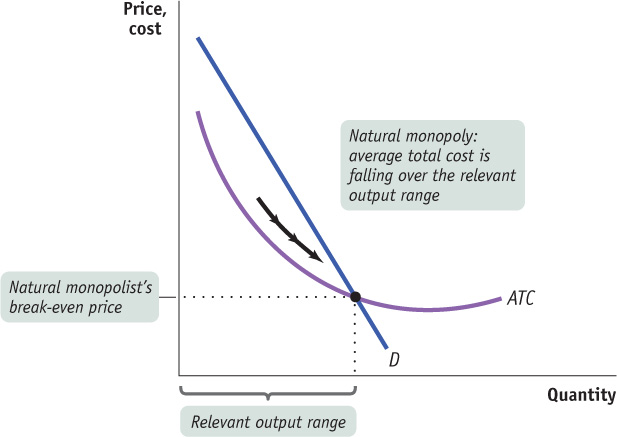

A monopoly created and sustained by increasing returns to scale is called a natural monopoly. The defining characteristic of a natural monopoly is that it possesses increasing returns to scale over the range of output that is relevant for the industry. This is illustrated in Figure 13-3, showing the firm’s average total cost curve, ATC, and the market demand curve, D. Here we can see that the natural monopolist’s ATC curve declines over the output levels at which price is greater than or equal to average total cost. So the natural monopolist has increasing returns to scale over the entire range of output for which any firm would want to remain in the industry—the range of output at which the firm would at least break even in the long run. The source of this condition is large fixed costs: when large fixed costs are required to operate, a given quantity of output is produced at lower average total cost by one large firm than by two or more smaller firms.

A natural monopoly exists when increasing returns to scale provide a large cost advantage to a single firm that produces all of an industry’s output.

The most visible natural monopolies in the modern economy are local utilities—water, gas, and sometimes electricity. As we’ll see later in this chapter, natural monopolies pose a special challenge to public policy.

3. Technological Superiority A firm that maintains a consistent technological advantage over potential competitors can establish itself as a monopolist. For example, from the 1970s through the 1990s the chip manufacturer Intel was able to maintain a consistent advantage over potential competitors in both the design and production of microprocessors, the chips that run computers. But technological superiority is typically not a barrier to entry over the longer term: over time competitors will invest in upgrading their technology to match that of the technology leader. In fact, in the last few years Intel found its technological superiority eroded by a competitor, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), which now produces chips approximately as fast and as powerful as Intel chips.

We should note, however, that in certain high-tech industries, technological superiority is not a guarantee of success against competitors because of network externalities.

4. Network Externality If you were the only person in the world with an Internet connection, what would that connection be worth to you? The answer, of course, is nothing. Your Internet connection is valuable only because other people are also connected. And, in general, the more people who are connected, the more valuable your connection is. This phenomenon, whereby the value of a good or service to an individual is greater when many others use the same good or service, is called a network externality—its value derives from enabling its users to participate in a network of other users.

A network externality exists when the value of a good or service to an individual is greater when many other people use the good or service as well.

The earliest form of network externalities arose in transportation, where the value of a road or airport increased as the number of people who had access to it rose. But network externalities are especially prevalent in the technology and communications sectors of the economy. The classic case is computer operating systems. Worldwide, most personal computers run on Microsoft Windows. Although many believe that Apple has a superior operating system, the wider use of Windows in the early days of personal computers attracted more software development and technical support, giving it a lasting dominance.

When a network externality exists, the firm with the largest network of customers using its product has an advantage in attracting new customers, one that may allow it to become a monopolist. At a minimum, the dominant firm can charge a higher price and so earn higher profits than competitors. Moreover, a network externality gives an advantage to the firm with the “deepest pockets.” Companies with the most money on hand can sell the most goods at a loss with the expectation that doing so will give it the largest customer base.

5. Government-Created Barrier In 1999 the pharmaceutical company Merck Canada Inc. introduced Propecia, a drug effective against baldness. Despite the fact that Propecia was very profitable and other drug companies had the know-how to produce it, no other firms challenged Merck’s monopoly. That’s because in March 1999 the Canadian government had given Merck a patent for this drug. The patent gave Merck the sole legal right to produce the drug in Canada until the patent expired in 2014. Propecia is an example of a monopoly protected by government-created barriers.

The most important legally created monopolies today arise from patents and copyrights. A patent gives an inventor the sole right to make, use, or sell that invention for a period that in most countries lasts between 16 and 20 years. Patents are given to the creators of new products, such as drugs or devices. In Canada, the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO), a federal agency under Industry Canada, is responsible for the administration of intellectual property in Canada, including granting and registering patents, trademarks, copyright, and industrial designs. Currently, a Canadian patent grants an inventor the exclusive right to make, use, and sell his or her invention for up to 20 years from the day of filing a patent application. Similarly, a copyright gives the creator of a literary or artistic work the sole rights to profit from that work, usually for a period equal to the creator’s lifetime plus 50 years.

A patent gives an inventor a temporary monopoly in the use or sale of an invention.

A copyright gives the creator of a literary or artistic work sole rights to profit from that work.

THE PRICE WE PAY

Although providing cheap patent-protected drugs to patients in poor countries is a new phenomenon, charging different prices to consumers in different countries is not: it’s an example of price discrimination.

A monopolist will maximize profits by charging a higher price in the country with a lower price elasticity (the rich country) and a lower price in the country with a higher price elasticity (the poor country). Interestingly, however, drug prices can differ substantially even among countries with comparable income levels. How do we explain this?

The answer is differences in regulation.

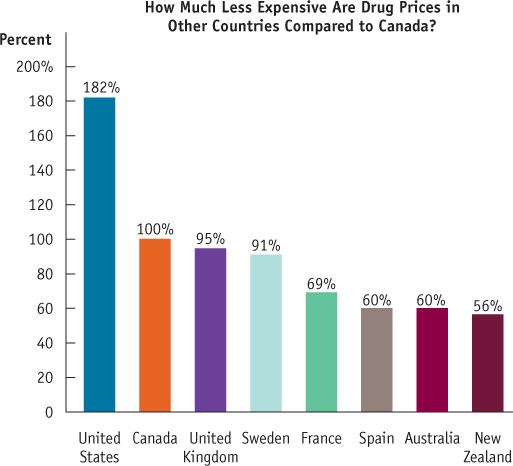

This graph compares the prices paid by residents of various wealthy countries for a given basket of drugs. It shows that American consumers pay much more for their drugs than residents of other wealthy countries. And while Canadians only pay 55% of what the Americans pay for drugs, the cost of drugs in Canada is nonetheless higher than in other countries such as France, Spain, and Australia. For example, Spaniards and Australians pay approximately 60% of what Canadians pay for drugs and only about one-third of what Americans pay. The reason: governments in these countries more actively regulate drug prices than Canada and the United States do, helping to keep drug prices affordable for their citizens.

To save money, it’s not surprising that Americans travel to Canada and Mexico to purchase their drugs, or buy them from abroad over the Internet.

Yet, American drug-makers contend that higher drug prices are necessary to cover the the high cost of research and development, which can run into the tens of millions of dollars over several years for successful drugs. Critics of the drug companies counter that American drug prices are in excess of what is needed for a socially desirable level of drug innovation. Instead, they say that drug companies are too often focused on developing drugs that generate high profits rather than those that improve health or save lives. What’s indisputable is that some level of profit is necessary to fund innovation.

Sources: U.S. Energy Information Administration; Natural Resources Canada, 2010.

The justification for patents and copyrights is a matter of incentives. If inventors are not protected by patents, they would gain little reward from their efforts: as soon as a valuable invention was made public, others would copy it and sell products based on it. And if inventors could not expect to profit from their inventions, then there would be no incentive to incur the costs of invention in the first place. Likewise for the creators of literary or artistic works. So the law gives a temporary monopoly that encourages invention and creation by imposing temporary property rights.

Patents and copyrights are temporary because the law strikes a compromise. The higher price for the good that holds while the legal protection is in effect compensates inventors for the cost of invention; conversely, the lower price that results once the legal protection lapses and competition emerges benefits consumers and increases economic efficiency.

Because the length of the temporary monopoly cannot be tailored to specific cases, this system is imperfect and leads to some missed opportunities. In some cases there can be significant welfare issues. For example, the violation of drug patents by pharmaceutical companies in poor countries has been a major source of controversy, pitting the needs of poor patients who cannot afford retail drug prices against the interests of drug manufacturers that have incurred high research costs to discover these drugs. To solve this problem, some drug companies and poor countries have negotiated deals in which the patents are honoured but the companies sell their drugs at deeply discounted prices. For example, GlaxoSmithKline, Canada’s leading flu vaccine manufacturer, has adopted a policy to not charge the least developed countries more than 25% of the price charged in the developed world for their patented medicines. (This is an example of price discrimination, which we’ll learn more about later in this chapter.)

NEWLY EMERGING MARKETS: A DIAMOND MONOPOLIST’S BEST FRIEND

When Cecil Rhodes created the De Beers monopoly, it was a particularly opportune moment. The new diamond mines in South Africa dwarfed all previous sources, so almost all of the world’s diamond production was concentrated in a few square kilometres.

Until recently, De Beers was able to extend its control of resources even as new mines opened. De Beers either bought out new producers or entered into agreements with local governments that controlled some of the new mines, effectively making them part of the De Beers monopoly. The most remarkable of these was an agreement with the former Soviet Union, which ensured that Russian diamonds would be marketed through De Beers, preserving its ability to control retail prices. De Beers also went so far as to stockpile a year’s supply of diamonds in its London vaults so that when demand dropped, newly mined stones would be stored rather than sold, restricting retail supply until demand and prices recovered.

However, over the past few years the De Beers monopoly has been under assault. Government regulators have forced De Beers to loosen its control of the market. For the first time, De Beers has competition: a number of independent companies have begun mining for diamonds in other African countries. In addition, high-quality, inexpensive synthetic dia monds have become an alternative to real gems, eating into De Beers’s profits. So does this mean an end to high diamond prices and De Beers’s high profits?

Not really. Although today’s De Beers is more of a “near-monopolist” than a true monopolist, it still mines more of the world’s supply of diamonds than any other single producer. And it has been benefitting from newly emerging markets. Consumer demand for diamonds has soared in countries like China and India, leading to price increases.

Nevertheless, the economic crisis of 2009 put a serious dent in worldwide demand for diamonds. De Beers responded by cutting 2011 production by 20% (compared to 2008). But affluent Chinese continue to be heavy buyers of diamonds, and De Beers anticipates that Asian demand will accelerate the depletion of the world’s existing diamond mines. As a result, diamond analysts predict rough diamond prices to rise by at least 5% per year for the next five years.

In the end, although a diamond monopoly may not be forever, a near-monopoly with rising demand in newly emerging markets may be just as profitable.

Quick Review

In a monopoly, a single firm uses its market power to charge higher prices and produce less output than a competitive industry, generating profits in the short and long run.

Profits will not persist in the long run unless there is a barrier to entry such as control of natural resources, increasing returns to scale, technological superiority, network externalities, or legal restrictions imposed by governments.

A natural monopoly arises when average total cost is declining over the output range relevant for the industry. This creates a barrier to entry because an established monopolist has lower average total cost than an entrant.

In certain technology and communications sectors of the economy, a network externality enables a firm with the largest number of customers to become a monopolist.

Patents and copyrights, government-created barriers, are a source of temporary monopoly that attempt to balance the need for higher prices as compensation to an inventor for the cost of invention against the increase in consumer surplus from lower prices and greater efficiency.

Check Your Understanding 13-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13-1

Question 13.1

Suppose Lamplighter New Brunswick is the only natural gas distributor in the province of New Brunswick. Last winter residents were shocked that the price of natural gas had increased drastically and believed that they were the victims of market power. Explain which of the following pieces of evidence support or contradict that conclusion.

There is a national shortage of natural gas, and Lamplighter New Brunswick could procure only a limited amount.

Last year, Lamplighter New Brunswick and several other competing local natural gas distributing firms merged into a single firm.

The cost to Lamplighter New Brunswick of purchasing natural gas from a natural gas processing plant has gone up significantly.

Recently, some nonlocal firms have begun to offer natural gas to Lamplighter New Brunswick’s regular customers at a price much lower than Lamplighter New Brunswick’s.

Lamplighter New Brunswick has acquired an exclusive government licence to draw natural gas from the only natural gas pipeline in the province.

This does not support the conclusion. Lamplighter New Brunswick has a limited amount of natural gas, and the price has risen in order to equalize supply and demand.

This supports the conclusion because the market for natural gas has become monopolized, and a monopolist will reduce the quantity supplied and raise price to generate profit.

This does not support the conclusion. Lamplighter New Brunswick has raised its price to consumers because the price of its input, natural gas, has increased.

This supports the conclusion. The fact that other firms have begun to supply natural gas at a lower price implies that Lamplighter New Brunswick must have earned sufficient profits to attract the other firms to New Brunswick.

This supports the conclusion. It indicates that Lamplighter New Brunswick enjoys a barrier to entry because it controls access to the only natural gas pipeline.

Question 13.2

Suppose the government is considering extending the length of a patent from 20 years to 30 years. How would this change each of the following?

The incentive to invent new products

The length of time during which consumers have to pay higher prices

Extending the length of a patent increases the length of time during which the inventor can reduce the quantity supplied and increase the market price. Since this increases the period of time during which the inventor can earn economic profits from the invention, it increases the incentive to invent new products.

Extending the length of a patent also increases the period of time during which consumers have to pay higher prices. So determining the appropriate length of a patent involves making a trade-off between the desirable incentive for invention and the undesirable high price to consumers.

Question 13.3

Explain the nature of the network externality in each of the following cases.

A new type of credit card, called Passport

A new type of car engine, which runs on solar cells

A website for trading locally provided goods and services

When a large number of other people use Passport credit cards, then any one merchant is more likely to accept the card. So the larger the customer base, the more likely a Passport card will be accepted for payment.

When a large number of people own a car with a new type of engine, it will be easier to find a knowledgeable mechanic who can repair it.

When a large number of people use such a website, the more likely it is that you will be able to find a buyer for something you want to sell or a seller for something you want to buy.