13.5 Price Discrimination

A single-price monopolist offers its product to all consumers at the same price.

Up to this point, we have considered only the case of a single-price monopolist, one that charges all consumers the same price. As the term suggests, not all monopolists do this. In fact, many if not most monopolists find that they can increase their profits by charging different customers different prices for the same good: they engage in price discrimination. There are three degrees of price discriminations: first-

Sellers engage in price discrimination when they charge different prices to different consumers for the same good.

The most striking example of price discrimination many of us encounter regularly involves airline tickets. Although there are a number of Canadian airlines (with Air Canada being the dominant firm), most domestic routes are serviced by only one or two carriers, which, as a result, have market power and can set prices. So any regular airline passenger quickly becomes aware that the question “How much will it cost me to fly there?” rarely has a simple answer.

If you are willing to buy a nonrefundable ticket a month in advance and stay over a Saturday night, a round trip between Toronto and Montreal, for example, may only cost you $250 or less (including taxes, fees, and surcharges). But if you have to go on a business trip tomorrow, which happens to be Tuesday, and come back on Wednesday, the same round trip might cost $550. Yet the business traveller and the tourist receive the same product—

You might object that airlines are not usually monopolists—

The Logic of Price Discrimination

To get a preliminary view of why price discrimination might be more profitable than charging all consumers the same price, imagine that Maple Sky offers the only nonstop flights between Toronto and Montreal. Assume that there are no capacity problems—

Further assume that the airline knows there are two kinds of potential passengers. First, there are business travellers, 2000 of whom want to travel between the destinations each week. Second, there are students, 2000 of whom also want to travel each week.

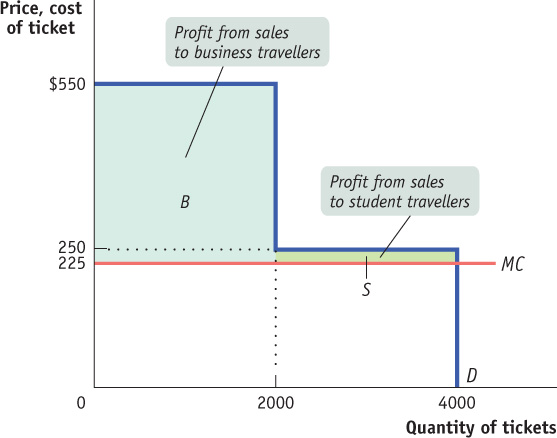

Will potential passengers take the flight? It depends on the price. The business travellers, it turns out, really need to fly; they will take the plane as long as the price is no more than $550. Since they are flying purely for business, we assume that cutting the price below $550 will not lead to any increase in business travel. The students, however, have less money and more time; if the price goes above $250, they will take the bus. The implied demand curve is shown in Figure 13-10.

So what should the airline do? If it has to charge everyone the same price, its options are limited. It could charge $550; that way it would get as much as possible out of the business travellers but lose the student market. Or it could charge only $250; that way it would get both types of travellers but would make significantly less money from sales to business travellers.

We can quickly calculate the profits from each of these alternatives. If the airline charged $550, it would sell 2000 tickets to the business travellers, earning total revenue of 2000 × $550 = $1.1 million and incurring costs of 2000 × $125 = $250 000; so its profit would be $850 000, illustrated by the shaded area B in Figure 13-10. If the airline charged only $250, it would sell 4000 tickets to the business travellers and students, receiving revenue of 4000 × $250 = $1 000 000 and incurring costs of 4000 × $225 = $900 000; so its profit would be $100 000. If the airline must charge everyone the same price, charging the higher price and forgoing sales to students is clearly more profitable.

What the airline would really like to do, however, is charge the business travellers the full $550 but offer $250 tickets to the students. That’s a lot less than the price paid by business travellers, but it’s still above marginal cost; so if the airline could sell those extra 2000 tickets to students, it would make an additional $50 000 in profit. That is, it would make a profit equal to the areas B plus S in Figure 13-10.

It would be more realistic to suppose that there is some “give” in the demand of each group: at a price below $550, there would be some increase in business travel; and at a price above $250, some students would still purchase tickets. But this, it turns out, does not do away with the argument for price discrimination. The important point is that the two groups of consumers differ in their sensitivity to price—that a high price has a larger effect in discouraging purchases by students than by business travellers. As long as different groups of customers respond differently to the price, a monopolist will find that it can capture more consumer surplus and increase its profit by charging them different prices. (Here we have assumed the monopolist can easily distinguish the two groups of customers and reselling from one group to the other is not possible.)

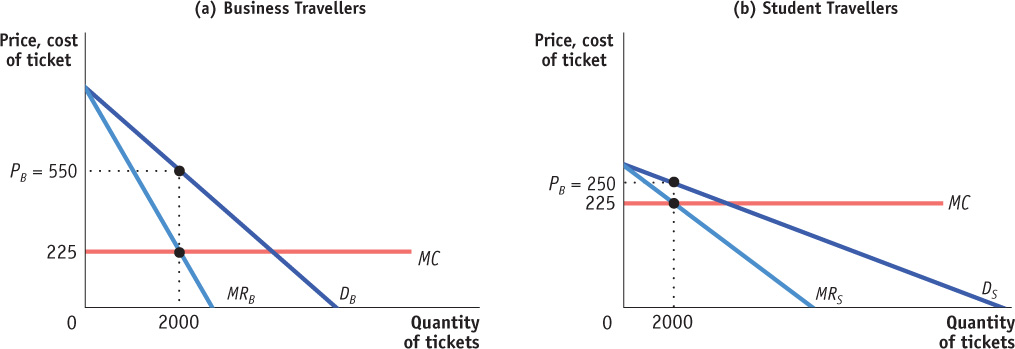

According to Figure 13-10, Maple Sky would maximize its profit by charging different airfares to different groups of travellers and in that figure the demand curve looks like a stepped function. The same logic applies when a firm faces downward sloping demand curves. Figure 13-11 shows how Maple Sky could maximize its profits for two groups of travellers with typical demand curves. When Maple Sky is able to charge different airfares, it will treat the market for student travellers separately from the market for business travellers. In each respective market, Maple Sky chooses the number of tickets sold such that marginal cost is equal to the marginal revenue (setting MC = MR in each market). This is considered third-

You may have noticed that, like the airline industry, attractions such as zoos, science centres, museums, and art galleries often offer different prices to different groups of customers, namely children, students, and seniors. How can these places offer admission discounts to these customers? Usually, seniors and children can be distinguished by their appearance. As for students, colleges and universities issue student ID cards, and student just need to show their valid ID to receive lower prices. Many Canadian schools take part in the International Student Identity Card (ISIC), which grants discounts on a range of activities from shopping at local retail stores to travelling abroad.

Price Discrimination and Elasticity

A more realistic description of the demand that airlines face would not specify particular prices at which different types of travellers would choose to fly. Instead, it would distinguish between the groups on the basis of their sensitivity to the price—

Suppose that a company sells its product to two easily identifiable groups of people—

The answer is the one already suggested by our simplified example: the company should charge business travellers, with their low price elasticity of demand, a higher price than it charges students, with their high price elasticity of demand. To achieve this price difference, several airlines and travel agencies offer discounts to students with valid identification, such as the ISIC card.

The actual situation of the airlines is very much like this hypothetical example. Business travellers typically place a high priority on being at the right place at the right time and are not very sensitive to the price. But nonbusiness travellers are fairly sensitive to the price: faced with a high price, they might take the bus, drive to another airport to get a lower fare, or skip the trip altogether.

So why doesn’t an airline simply announce different prices for business and nonbusiness customers? First, this would probably be illegal (the Competition Act places limits on the ability of companies to practise open price discrimination). Second, even if it were legal, it would be a hard policy to enforce: business travellers might be willing to wear casual clothing and claim they were visiting family in Montreal in order to save $300.

So what the airlines do—

Because customers must show their ID at check-

Perfect Price Discrimination

Let’s return to the example of business travellers and students travelling between Toronto and Montreal, illustrated in Figure 13-10, and ask what would happen if the airline could distinguish between the two groups of customers in order to charge each a different price.

Clearly, the airline would charge each group its willingness to pay—that is, as we learned in Chapter 4, the maximum that each group is willing to pay. For business travellers, the willingness to pay is $550; for students, it is $250. As we have assumed, the marginal cost is $225 and does not depend on output, making the marginal cost curve a horizontal line. As we noted earlier, we can easily determine the airline’s profit: it is the sum of the areas of the rectangle B and the rectangle S.

In this case, the consumers do not get any consumer surplus! The entire surplus is captured by the monopolist in the form of profit. When a monopolist is able to capture the entire surplus in this way, we say that it achieves perfect price discrimination (also called first-degree price discrimination).

Perfect price discrimination takes place when a monopolist charges each consumer his or her willingness to pay—the maximum that the consumer is willing to pay.

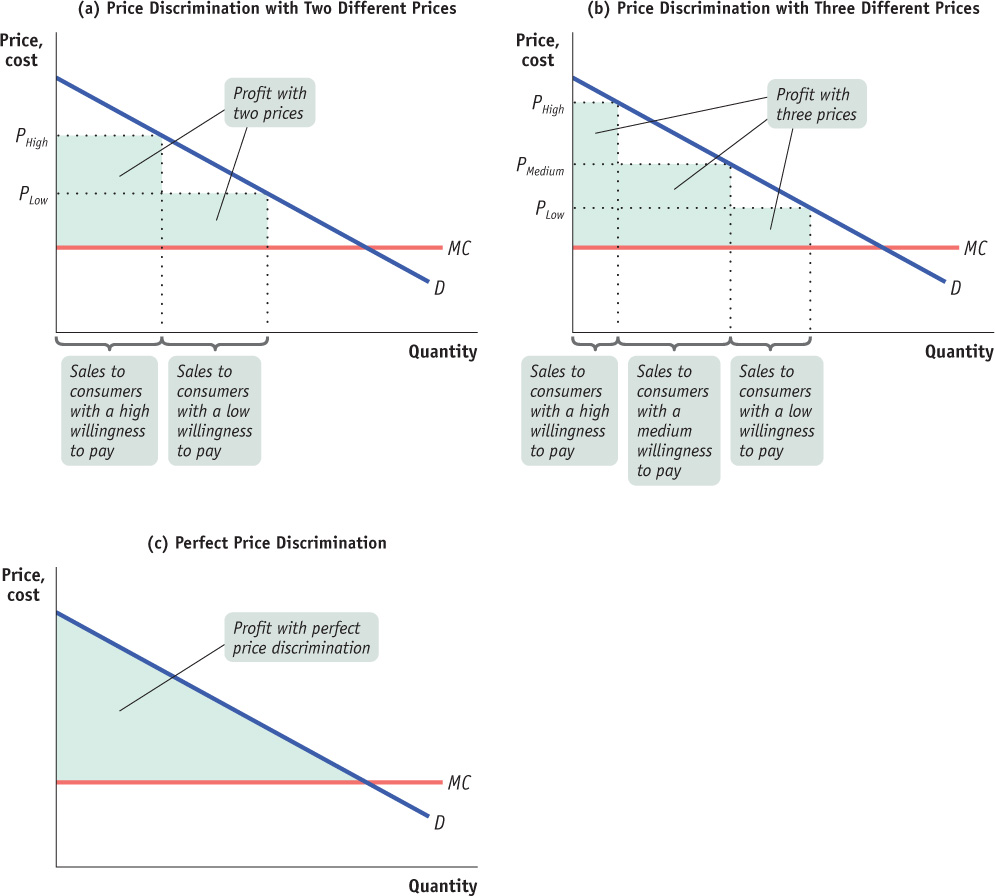

In general, the greater the number of different prices a monopolist is able to charge, the closer it can get to perfect price discrimination. Figure 13-12 shows a monopolist facing a downward-sloping demand curve, a monopolist who we assume is able to charge different prices to different groups of consumers, with the consumers who are willing to pay the most being charged the most. In panel (a) the monopolist charges two different prices; in panel (b) the monopolist charges three different prices. Two things are apparent:

The greater the number of prices the monopolist charges, the lower the lowest price—that is, some consumers will pay prices that approach marginal cost.

The greater the number of prices the monopolist charges, the more money it extracts from consumers.

With a very large number of different prices, the picture would look like panel (c), a case of perfect price discrimination. Here, consumers least willing to buy the good pay marginal cost, and the entire consumer surplus is extracted as profit.

Both our airline example and the example in Figure 13-12 can be used to make another point: a monopolist that can engage in perfect price discrimination doesn’t cause any inefficiency! The reason is that the source of inefficiency is eliminated: all potential consumers who are willing to purchase the good at a price equal to or above marginal cost are able to do so. The perfectly price-discriminating monopolist manages to “scoop up” all consumers by offering some of them lower prices than it charges others. The entire surplus is captured by producer surplus, and the deadweight loss is zero.

Perfect price discrimination is almost never possible in practice. At a fundamental level, the inability to achieve perfect price discrimination is a problem of prices as economic signals, a phenomenon we noted in Chapter 4. When prices work as economic signals, they convey the information needed to ensure that all mutually beneficial transactions will indeed occur: the market price signals the seller’s cost, and a consumer signals willingness to pay by purchasing the good whenever that willingness to pay is at least as high as the market price.

The problem in reality, however, is that prices are often not perfect signals: a consumer’s true willingness to pay can be disguised, as by a business traveller who claims to be a student when buying a ticket in order to obtain a lower fare. When such disguises work, a monopolist cannot achieve perfect price discrimination.

However, monopolists do try to move in the direction of perfect price discrimination through a variety of pricing strategies. Common techniques for price discrimination include the following:

Advance purchase restrictions. Prices are lower for those who purchase well in advance (or in some cases for those who purchase at the last minute). This separates those who are likely to shop for better prices from those who won’t.

Volume discounts. Often the price is lower if you buy a large quantity. For a consumer who plans to consume a lot of a good, the cost of the last unit—the marginal cost to the consumer—is considerably less than the average price. This separates those who plan to buy a lot and so are likely to be more sensitive to price from those who don’t.

Two-part tariffs. With a two-part tariff, a customer plays a flat fee upfront and then a per-unit fee on each item purchased. So in a discount club like Costco or Sam’s Club (which are not monopolists but monopolistic competitors), you pay an annual fee in addition to the cost of the items you purchase. So the cost of the first item you buy is in effect much higher than that of subsequent items, making the two-part tariff behave like a volume discount.

Volume discounts and two-part tariffs are second-degree price discriminations. In these cases, the monopolist charges different prices based on the quantity purchased by its customers because the monopolist knows it has different groups of customers but is unable to differentiate them easily. By charging different prices based on the quantity purchased the monopolist is making its customers reveal their own preference by choosing the packages offered.

Our discussion also helps explain why government policies on monopoly typically focus on preventing deadweight losses, rather than preventing price discrimination—unless it causes serious issues of equity. The Competition Bureau, the federal agency responsible for Canada’s competition policy, focuses on price discrimination for sales in input or wholesale markets rather than in retail markets. Doing so ensures that firms are charged the same input prices, so no supplier can affect competition at the retail level. Compared to a single-price monopolist, price discrimination—even when it is not perfect—can increase the efficiency of the market. If sales to consumers formerly priced out of the market but now able to purchase the good at a lower price generate enough surplus to offset the loss in surplus to those now facing a higher price and no longer buying the good, then total surplus increases when price discrimination is introduced.

An example of this might be a drug that is disproportionately prescribed to senior citizens, who are often on fixed incomes and so are very sensitive to price. A policy that allows a drug company to charge senior citizens a low price and everyone else a high price may indeed increase total surplus compared to a situation in which everyone is charged the same price. But price discrimination that creates serious concerns about equity is likely to be prohibited—for example, an ambulance service that charges patients based on the severity of their emergency.

SALES, FACTORY OUTLETS, AND GHOST CITIES

Have you ever wondered why department stores occasionally hold sales, offering their merchandise for considerably less than the usual prices? Or why, driving along Canadian highways, you sometimes encounter clusters of “factory outlet” stores, often a couple of hours’ drive from the nearest city?

These familiar features of the economic landscape are actually rather peculiar if you think about them: why should sheets and towels be suddenly cheaper for a week each winter, or raincoats be offered for less in Halton Hills, just west of Toronto, than in Toronto itself? In each case the answer is that the sellers—who are often oligopolists or monopolistic competitors—are engaged in a subtle form of price discrimination.

Why hold regular sales of sheets and towels? Stores are aware that some consumers buy these goods only when they discover that they need them; they are not likely to put a lot of effort into searching for the best price and so have a relatively low price elasticity of demand. So the store wants to charge high prices for customers who come in on an ordinary day. But shoppers who plan ahead, looking for the lowest price, will wait until there is a sale. By scheduling such sales only now and then, the store is in effect able to price-discriminate between high-elasticity and low-elasticity customers.

An outlet store serves the same purpose: by offering merchandise for low prices, but only at a considerable distance away, a seller is able to establish a separate market for those customers who are willing to make a significant effort to search out lower prices—and who therefore have a relatively high price elasticity of demand.

Finally, let’s return to airline tickets to mention one of the truly odd features of their prices. Often a flight from one major destination to another—say, from Vancouver to Montreal—is slightly cheaper than a shorter flight to a smaller city—say, from Vancouver to Ottawa. Again, the reason is a difference in the price elasticity of demand: customers have a choice of many airlines between Vancouver and Montreal, so the demand for any one flight is quite elastic; customers have very little choice in flights to a smaller city, so the demand is much less elastic.

But often there is a flight between two major destinations that makes a stop along the way—say, a flight from Vancouver to Montreal with a stop in Ottawa. In these cases, it is sometimes cheaper to fly to the more distant city than to the city that is a stop along the way. For example, it may be cheaper to purchase a ticket to Montreal and get off in Ottawa than to purchase a ticket to Ottawa! It sounds ridiculous but makes perfect sense given the logic of monopoly pricing.

So why don’t passengers simply buy a ticket from Vancouver to Montreal, but get off at Ottawa? Well, some do—but the airlines, understandably, make it difficult for customers to find out about such “ghost cities.” In addition, the airline will not allow you to check baggage only part of the way if you have a ticket for the final destination. And airlines refuse to honour tickets for return flights when a passenger has not completed all the legs of the outbound flight. All these restrictions are meant to enforce the separation of markets necessary to allow price discrimination.

Quick Review

Not every monopolist is a single-price monopolist. Many monopolists, as well as oligopolists and monopolistic competitors, engage in price discrimination.

Price discrimination is profitable when consumers differ in their sensitivity to the price. A monopolist charging higher prices to low-elasticity consumers and lower prices to high-elasticity ones.

A monopolist able to charge each consumer his or her willingness to pay for the good achieves perfect price discrimination and does not cause inefficiency because all mutually beneficial transactions are exploited.

Check Your Understanding 13-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13-4

Question 13.9

True or false? Explain your answer.

A single-price monopolist sells to some customers that a price-discriminating monopolist refuses to.

A price-discriminating monopolist creates more inefficiency than a single-price monopolist because it captures more of the consumer surplus.

Under price discrimination, a customer with highly elastic demand will pay a lower price than a customer with inelastic demand.

False. A price-discriminating monopolist will sell to some customers that a single-price monopolist will refuse to—namely, customers with a high price elasticity of demand who are willing to pay only a relatively low price for the good.

False. Although a price-discriminating monopolist does indeed capture more of the consumer surplus, inefficiency is lower: more mutually beneficial transactions occur because the monopolist makes more sales to customers with a low willingness to pay for the good.

True. Under price discrimination consumers are charged prices that depend on their price elasticity of demand. A consumer with highly elastic demand will pay a lower price than a consumer with inelastic demand.

Question 13.10

Which of the following are cases of price discrimination and which are not? In the cases of price discrimination, identify the consumers with high and those with low price elasticity of demand.

Damaged merchandise is marked down.

Restaurants have senior citizen discounts.

Food manufacturers place discount coupons for their merchandise in newspapers.

Airline tickets cost more during the summer peak flying season.

This is not a case of price discrimination because all consumers, regardless of their price elasticities of demand, value the damaged merchandise less than undamaged merchandise. So the price must be lowered to sell the merchandise.

This is a case of price discrimination. Senior citizens have a higher price elasticity of demand for restaurant meals (their demand for restaurant meals is more responsive to price changes) than other patrons. Restaurants lower the price to high-elasticity consumers (senior citizens). Consumers with low price elasticity of demand will pay the full price.

This is a case of price discrimination. Consumers with a high price elasticity of demand will pay a lower price by collecting and using discount coupons. Consumers with a low price elasticity of demand will not use coupons.

This is not a case of price discrimination; it is simply a case of supply and demand.

Macmillan Stares Down Amazon

The normally genteel world of book publishing was anything but in early 2010. War had broken out between Macmillan, a large book publisher, and Amazon.com, the giant Internet book retailer. As one industry insider commented, “everyone thought they were witnessing a knife fight.”

In early 2010, Amazon.com dominated the market for ebooks because it owned the best technology platform for distribution at the time: the Kindle, which lets users download books directly from Amazon.com’s website. Although some publishers worried that readers’ switch from paper books to ebooks would hurt sales, it seemed equally plausible that e-readers would actually increase them. Why? Because e-readers are so convenient to use and ebooks can’t be turned into second-hand bargains. Yet book publishers were not at all happy with Amazon’s behaviour in the ebook market.

What had spoiled their relationship was Amazon’s policy of pricing every ebook at $9.99, a price at which it incurred a loss once it had paid the publisher for the book’s copyright. Amazon argued that publishers should welcome its pricing because it would encourage more people to buy ebooks. Publishers, though, worried that the $9.99 price would cut into their sales of printed books. Moreover, Amazon didn’t set a higher retail price for ebooks by premium authors, thereby undermining their special status. Perhaps most worrying was the prospect that Amazon would come to permanently dominate the ebook market, becoming the gatekeeper between publishers and readers.

Despite publishers’ protests, Amazon refused to budge on its pricing. Matters came to a head in early February 2010, just as Apple was getting ready to launch its iPad, which has an ebook application. After John Sargent, the CEO of Macmillan, was unable to come to an agreement with Amazon, during a tense face-to-face meeting, the retailer removed all Macmillan books—paper and ebooks, even bestsellers—from its website (except for those purchased through third-party sellers).

After a barrage of bad press, Amazon backed down and agreed to allow Macmillan to set the retail price for its books, with Amazon receiving a 30% commission for each book sold, rather than the more common difference between the retail price and the wholesale price. Those terms closely replicated the terms agreed to by the largest publishers and Apple a week earlier.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 13.11

What accounts for Amazon’s willingness to incur a loss on its ebook sales? Relate its actions to a concept discussed in this chapter.

What accounts for Amazon’s willingness to incur a loss on its ebook sales? Relate its actions to a concept discussed in this chapter.

Question 13.12

Were publishers right to be fearful of Amazon’s pricing policy despite the fact that it probably generated higher ebook sales?

Were publishers right to be fearful of Amazon’s pricing policy despite the fact that it probably generated higher ebook sales?

Question 13.13

How do you think the entry of the Apple iPad into the e-reader market affected the dynamics between publishers and Amazon.com? Why do you think a major publisher like Macmillan was able to force Amazon to retreat from its pricing policy?

How do you think the entry of the Apple iPad into the e-reader market affected the dynamics between publishers and Amazon.com? Why do you think a major publisher like Macmillan was able to force Amazon to retreat from its pricing policy?