15.3 Understanding Monopolistic Competition

Suppose an industry is monopolistically competitive: it consists of many producers, all competing for the same consumers but offering differentiated products. How does such an industry behave?

As the term monopolistic competition suggests, this market structure combines some features typical of monopoly with others typical of perfect competition. Because each firm is offering a distinct product, it is in a way like a monopolist: it faces a downward-

The same, of course, is true of an oligopoly. In a monopolistically competitive industry, however, there are many producers, as opposed to the small number that defines an oligopoly. This means that the “puzzle” of oligopoly—

Monopolistic Competition in the Short Run

We introduced the distinction between short-

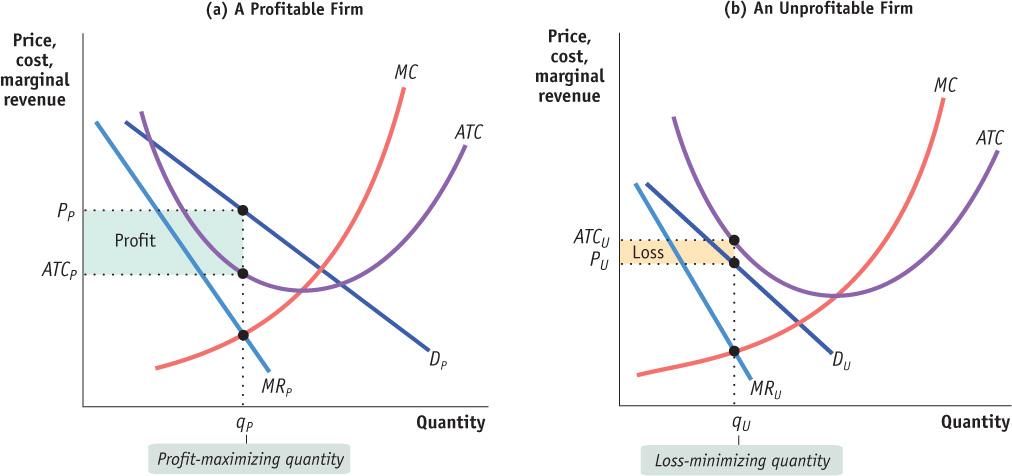

Panels (a) and (b) of Figure 15-1 show two possible situations that a typical firm in a monopolistically competitive industry might face in the short run. In each case, the firm looks like any monopolist: it faces a downward-

We assume that every firm has an upward-

In each case the firm, in order to maximize profit, sets marginal revenue equal to marginal cost. So how do these two figures differ? In panel (a) the firm is profitable; in panel (b) it is unprofitable. (Recall that we are referring always to economic profit, not accounting profit—

In panel (a) the firm faces the demand curve DP and the marginal revenue curve MRP. It produces the profit-

In panel (b) the firm faces the demand curve DU and the marginal revenue curve MRU. It chooses the quantity qU at which marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. However, in this case the price PU is below the average total cost ATCU; so at this quantity the firm loses money. Its loss is equal to the area of the shaded rectangle. Since qU is the profit-

As this comparison suggests, the key to whether a firm with market power is profitable or unprofitable in the short run lies in the relationship between its demand curve and its average total cost curve. In panel (a) the demand curve DP crosses the average total cost curve, meaning that some of the demand curve lies above the average total cost curve. So there are some price–

In panel (b), by contrast, the demand curve DU does not cross the average total cost curve—

These figures, showing firms facing downward-

Monopolistic Competition in the Long Run

Obviously, an industry in which existing firms are losing money, like the one in panel (b) of Figure 15-1, is not in long-run equilibrium. When existing firms are losing money, some firms will exit the industry. The industry will not be in long-run equilibrium until the persistent losses have been eliminated by the exit of some firms.

It may be less obvious that an industry in which existing firms are earning profits, like the one in panel (a) of Figure 15-1, is also not in long-run equilibrium. Given that there is free entry into the industry, persistent profits earned by the existing firms will lead to the entry of additional producers. The industry will not be in long-run equilibrium until the persistent profits have been eliminated by the entry of new producers.

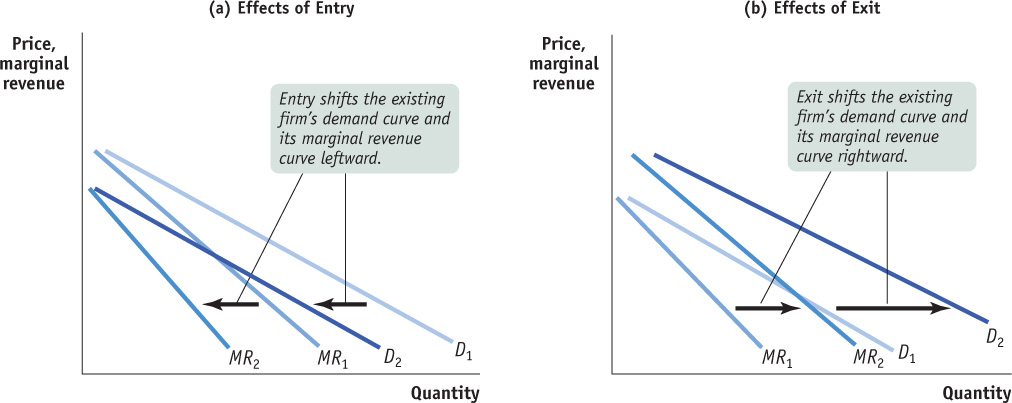

How will entry or exit by other firms affect the profits of a typical existing firm? Because the differentiated products offered by firms in a monopolistically competitive industry compete for the same set of customers, entry or exit by other firms will affect the demand curve facing every existing producer. If new gas stations open along a highway, each of the existing gas stations will no longer be able to sell as much gas as before at any given price. So, as illustrated in panel (a) of Figure 15-2, entry of additional producers into a monopolistically competitive industry will lead to a leftward shift of the demand curve and the marginal revenue curve facing a typical existing producer.

Conversely, suppose that some of the gas stations along the highway close. Then each of the remaining stations will be able to sell more gasoline at any given price. So, as illustrated in panel (b), exit of firms from an industry will lead to a rightward shift of the demand curve and marginal revenue curve facing a typical remaining producer.

The industry will be in long-run equilibrium when there is neither entry nor exit. This will occur only when every firm earns zero profit. So in the long run, a monopolistically competitive industry will end up in zero-profit equilibrium, in which firms just manage to cover their costs at their profit-maximizing output quantities.

In the long run, a monopolistically competitive industry ends up in zero-profit equilibrium: each firm makes zero profit at its profit-maximizing quantity.

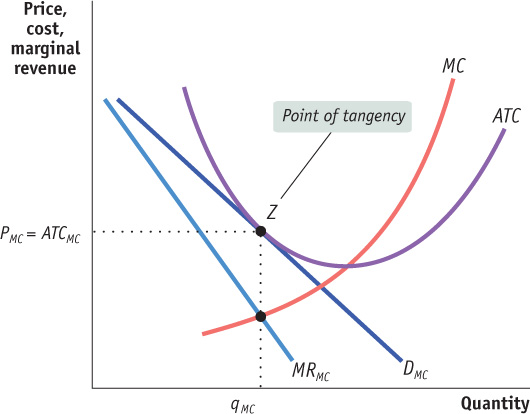

We have seen that a firm facing a downward-sloping demand curve will earn positive profits if any part of that demand curve lies above its average total cost curve; it will incur a loss if its demand curve lies everywhere below its average total cost curve. So in zero-profit equilibrium, the firm must be in a borderline position between these two cases; its demand curve must just touch its average total cost curve. That is, it must be just tangent to it at the firm’s profit-maximizing output quantity—the output quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

If this is not the case, the firm operating at its profit-maximizing quantity will find itself making either a profit or loss, as illustrated in the panels of Figure 15-1. But we also know that free entry and exit means that this cannot be a long-run equilibrium. Why? In the case of a profit, new firms will enter the industry, shifting the demand curve of every existing firm leftward until all profits are extinguished. In the case of a loss, some existing firms will exit and so shift the demand curve of every remaining firm to the right until all losses are extinguished. All entry and exit ceases only when every existing firm makes zero profit at its profit-maximizing quantity of output.

HITS AND FLOPS

On the face of it, the movie business seems to meet the criteria for monopolistic competition. Movies compete for the same consumers; each movie is different from the others; new companies can and do enter the business. But where’s the zero-profit equilibrium? After all, some movies are enormously profitable.

The key is to realize that for every successful blockbuster, there are several flops—and that the movie studios don’t know in advance which will be which. (One observer of Hollywood summed up his conclusions as follows: “Nobody knows anything.”) And by the time it becomes clear that a movie will be a flop, it’s too late to cancel it.

The difference between movie-making and the type of monopolistic competition we model in this chapter is that the fixed costs of making a movie are also sunk costs—once they’ve been incurred, they can’t be recovered.

Yet there is still, in a way, a zero-profit equilibrium. If movies on average were highly profitable, more studios would enter the industry and more movies would be made. If movies on average lost money, fewer movies would be made. In fact, as you might expect, the movie industry on average earns just about enough to cover the cost of production—that is, it earns roughly zero economic profit.

This kind of situation—in which firms earn zero profit on average but have a mixture of highly profitable hits and money-losing flops—can be found in other industries characterized by high up-front sunk costs. A notable example is the pharmaceutical industry, where many research projects lead nowhere but a few lead to highly profitable drugs.

Figure 15-3 shows a typical monopolistically competitive firm in such a zero-profit equilibrium. The firm produces qMC, the output at which MRMC = MC, and charges price PMC. At this price and quantity, represented by point Z, the demand curve is just tangent to its average total cost curve. The firm earns zero profit because price, PMC, is equal to average total cost, ATCMC.

The normal long-run condition of a monopolistically competitive industry, then, is that each producer is in the situation shown in Figure 15-3. Each producer acts like a monopolist, facing a downward-sloping demand curve and setting marginal cost equal to marginal revenue so as to maximize profits. But this is just enough to achieve zero economic profit. The producers in the industry are like monopolists without monopoly profits.

A REALTY CHECK

The vast majority of home sales in Canada are transacted with real estate agents. A homeowner looking to sell hires an agent, who lists the home for sale and shows it to interested buyers. Correspondingly, prospective homebuyers hire their own agents to arrange inspections of available homes. Traditionally, agents were paid, by the seller, a commission equal to a certain percentage of the sale price of the home, which the seller’s agent and the buyer’s agent would split equally. In Canada, there isn’t a set or standard commission percentage; the commission rate a seller pays depends on where the real estate is located. According to the Real Estate Council of Ontario, home sellers can choose from three different commission arrangements: a lump-sum amount, a fixed percentage of the sales price, or a combination of the two. While the commission rate is negotiable, the standard commission rate is 5%. Sellers in Alberta and British Columbia face a two-tiered rate system. For example, sellers in Vancouver pay 7% on the first $100 000 and 3 to 3.5 percent on the remaining balance of the real estate sale price. (Strictly speaking, the commission rate is negotiable between the seller and their agent. We are quoting the usual rates here.)

The real estate brokerage industry is a huge industry; based on an average 5% commission, real estate agents took in more than $8 billion in commission revenue across Canada in 2012. The industry fits the model of monopolistic competition quite well: in any given local market, there are many real estate agents, all competing with one another, but the agents are differentiated by location and personality as well as by the type of home they sell (some focus on condominiums, others on rural homes, and so on). And the industry has free entry.

But for a long time there was one feature that didn’t fit the model of monopolistic competition: the standard commission that had not changed over time and was unaffected by the ups and downs of the housing market. For example, in Toronto, where house prices doubled over a period of 12 years, agents received double the compensation on an average transaction as they had 12 years earlier even though the work was no harder.

You may wonder how agents were able to maintain a standard commission. Why didn’t new agents enter the market and drive the commission down to the zero-profit level? One tactic used by agents was their control of the Multiple Listing Service, or MLS, which lists nearly all the homes for sale in a community. Traditionally, only sellers who agreed to that fixed rate commission were allowed to list their homes on the MLS.

But protecting standard commissions was always an iffy endeavour because any action by the brokerage industry to fix the commission rate at a given percentage would run afoul of Canada’s competition laws. Indeed, changes are coming. In 2010, after an investigation by the Competition Bureau, the Canadian Real Estate Association, which represents all real estate agents in the country and owns MLS and realtor.ca, allowed brokers to post a listing on their sites for a flat fee. The Competition Bureau continues to investigate, negotiate, and litigate with Canada’s large realtor bodies in an attempt to get them to change their practices to allow greater entry and competition by other realtors—including those who offer much lower fees.

Quick Review

Like a monopolist, each firm in a monopolistically competitive industry faces a downward-sloping demand curve and marginal revenue curve. In the short run, it may earn a profit or incur a loss at its profit-maximizing quantity.

If the typical firm earns positive profit, new firms will enter the industry in the long run, shifting each existing firm’s demand curve to the left. If the typical firm incurs a loss, some existing firms will exit the industry in the long run, shifting the demand curve of each remaining firm to the right.

The long-run equilibrium of a monopolistically competitive industry is a zero-profit equilibrium in which firms just break even. The typical firm’s demand curve is tangent to its average total cost curve at its profit-maximizing quantity.

Check Your Understanding 15-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15-2

Question 15.3

Currently a monopolistically competitive industry, composed of firms with U-shaped average total cost curves, is in long-run equilibrium. Describe how the industry adjusts, in both the short and long run, in each of the following situations.

A technological change increases fixed cost for every firm in the industry.

A technological change decreases marginal cost for every firm in the industry.

An increase in fixed cost raises average total cost and shifts the average total cost curve upward. In the short run, firms incur losses. In the long run, some will exit the industry, resulting in a rightward shift of the demand curves for those firms that remain in the industry, since each one now serves a larger share of the market. Long-run equilibrium is reestablished when the demand curve for each remaining firm has shifted rightward to the point where it is tangent to the firm’s new, higher average total cost curve. At this point each firm’s price just equals its average total cost, and each firm makes zero profit.

A decrease in marginal cost lowers average total cost and shifts the average total cost curve and the marginal cost curve downward. Because existing firms now make profits, in the long run new entrants are attracted into the industry. In the long run, this results in a leftward shift of each existing firm’s demand curve since each firm now has a smaller share of the market. Long-run equilibrium is reestablished when each firm’s demand curve has shifted leftward to the point where it is tangent to the new, lower average total cost curve. At this point each firm’s price just equals average total cost, and each firm makes zero profit.

Question 15.4

Why, in the long run, is it impossible for firms in a monopolistically competitive industry to create a monopoly by joining together to form a single firm?

If all the existing firms in the industry joined together to create a monopoly, they would achieve monopoly profits. But this would induce new firms to create new, differentiated products and then enter the industry and capture some of the monopoly profits. So in the long run it would be impossible to maintain a monopoly. The problem arises from the fact that because free entry means new firms can create new products, there is no barrier to entry that can maintain a monopoly.