15.4 Monopolistic Competition versus Perfect Competition

In a way, long-

However, the two versions of long-

Price, Marginal Cost, and Average Total Cost

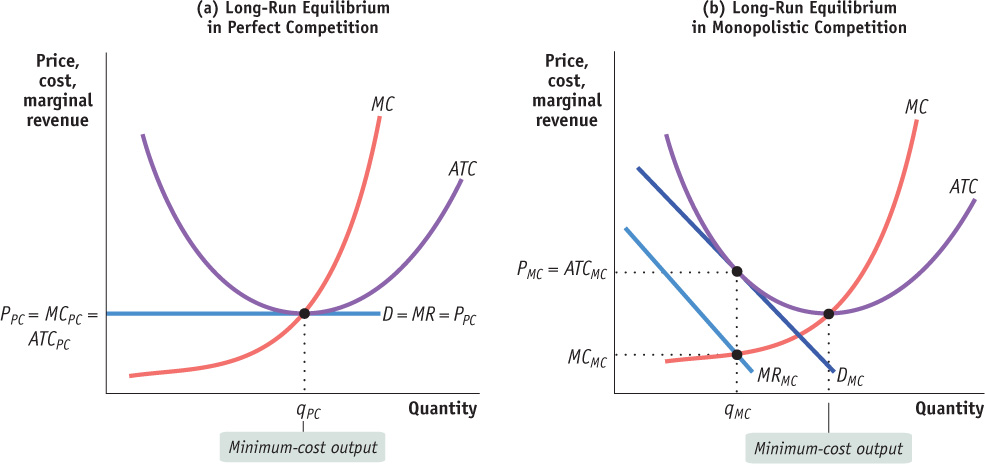

Figure 15-4 compares the long-

First, in the case of the perfectly competitive firm shown in panel (a), the price, PPC, received by the firm at the profit-

This difference translates into a difference in the attitude of firms toward consumers. A wheat farmer, who can sell as much wheat as he likes at the going market price, would not get particularly excited if you offered to buy some more wheat at the market price. Since he has no desire to produce more at that price and can sell the wheat to someone else, you are not doing him a favour.

But if you decide to fill up your tank at Jamil’s gas station rather than at Katy’s, you are doing Jamil a favour. He is not willing to cut his price to get more customers—

The fact that monopolistic competitors, unlike perfect competitors, want to sell more at the going price is crucial to understanding why they engage in activities like advertising that help increase sales.

The other difference between monopolistic competition and perfect competition that is visible in Figure 15-4 involves the position of each firm on its average total cost curve. In panel (a), the perfectly competitive firm produces at point qPC, at the bottom of the U-

Firms in a monopolistically competitive industry have excess capacity: they produce less than the output at which average total cost is minimized.

Under monopolistic competition, in panel (b), the firm produces at qMC, on the downward-

Some people have argued that, because every monopolistic competitor has excess capacity, monopolistically competitive industries are inefficient. But the issue of efficiency under monopolistic competition turns out to be a subtle one that does not have a clear answer.

Is Monopolistic Competition Inefficient?

A monopolistic competitor, like a monopolist, charges a price that is above marginal cost. As a result, some people who are willing to pay at least as much for an egg roll at Wonderful Wok as it costs to produce it are deterred from doing so. In monopolistic competition, some mutually beneficial transactions go unexploited.

Furthermore, it is often argued that monopolistic competition is subject to a further kind of inefficiency: that the excess capacity of every monopolistic competitor implies wasteful duplication because monopolistically competitive industries offer too many varieties. According to this argument, it would be better if there were only two or three vendors in the food court, not six or seven. If there were fewer vendors, they would each have lower average total costs and so could offer food more cheaply.

Is this argument against monopolistic competition right—that it lowers total surplus by causing inefficiency? Not necessarily. It’s true that if there were fewer gas stations along a highway, each gas station would sell more gasoline and so would have lower costs per litre. But there is a drawback: drivers would be inconvenienced because gas stations would be farther apart. The point is that the diversity of products offered in a monopolistically competitive industry is beneficial to consumers. So the higher price consumers pay because of excess capacity is offset to some extent by the value they receive from greater diversity.

There is, in other words, a trade-off: more producers means higher average total costs but also greater product diversity. Does a monopolistically competitive industry arrive at the socially optimal point on this trade-off? Probably not—but it is hard to say whether there are too many firms or too few! Most economists now believe that duplication of effort and excess capacity in monopolistically competitive industries are not important issues in practice.

Quick Review

In the long-run equilibrium of a monopolistically competitive industry, there are many firms, each earning zero profit.

Price exceeds marginal cost, so some mutually beneficial trades are unexploited.

Monopolistically competitive firms have excess capacity because they do not minimize average total cost. But it is not clear that this is actually a source of inefficiency since consumers gain from product diversity.

Check Your Understanding 15-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15-3

Question 15.5

True or false? Explain your answers.

Like a firm in a perfectly competitive industry, a firm in a monopolistically competitive industry is willing to sell a good at any price that equals or exceeds marginal cost.

Suppose there is a monopolistically competitive industry in long-run equilibrium that possesses excess capacity. All the firms in the industry would be better off if they merged into a single firm and produced a single product, but whether consumers are made better off by this is ambiguous.

Fads and fashions are more likely to arise in monopolistic competition or oligopoly than in monopoly or perfect competition.

False. As can be seen from panel (b) of Figure 15-4, a monopolistically competitive firm produces at a point where price exceeds marginal cost—unlike a perfectly competitive firm, which produces where price equals marginal cost (at the point of minimum average total cost). A monopolistically competitive firm will refuse to sell at marginal cost. This would be below average total cost and the firm would incur a loss.

True. Firms in a monopolistically competitive industry could achieve higher profits (monopoly profits) if they all joined together and produced a single product. In addition, since the industry possesses excess capacity, producing a larger quantity of output would lower the firm’s average total cost. The effect on consumers, however, is ambiguous. They would experience less choice. But if consolidation substantially reduces industry-wide average total cost and therefore substantially increases industry-wide output, consumers may experience lower prices under monopoly.

True. Fads and fashions are created and promulgated by advertising, which is found in oligopolies and monopolistically competitive industries but not in monopolies or perfectly competitive industries.