15.5 Controversies About Product Differentiation

Up to this point, we have assumed that products are differentiated in a way that corresponds to some real desire of consumers. There is real convenience in having a gas station in your neighbourhood; Chinese food and Mexican food are really different from each other.

In the real world, however, some instances of product differentiation can seem puzzling if you think about them. What is the real difference between Crest and Colgate toothpaste? Between Energizer and Duracell batteries? Or a Marriott and a Hilton hotel room? Most people would be hard-

No discussion of product differentiation is complete without spending at least a bit of time on the two related issues—

The Role of Advertising

Wheat farmers don’t advertise their wares on TV, but car dealers do. That’s not because farmers are shy and car dealers are outgoing; it’s because advertising is worthwhile only in industries in which firms have at least some market power.

The purpose of advertisements is to convince people to buy more of a seller’s product at the going price. A perfectly competitive firm, which can sell as much as it likes at the going market price, has no incentive to spend money convincing consumers to buy more. Only a firm that has some market power, and that therefore charges a price above marginal cost, can gain from advertising. (Industries that are more or less perfectly competitive, like the milk industry, do advertise—

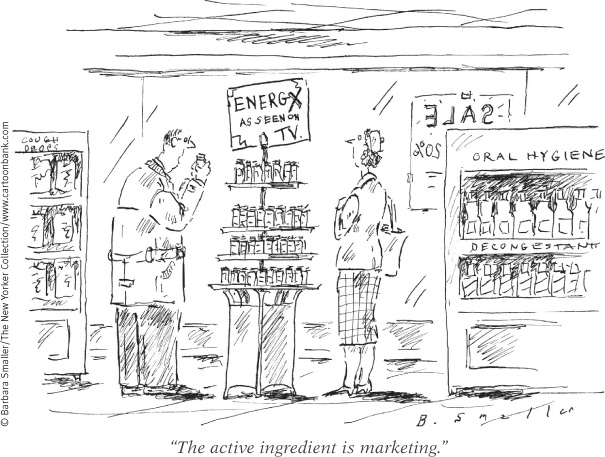

Given that advertising “works,” it’s not hard to see why firms with market power would spend money on it. But the big question about advertising is why it works. A related question is whether advertising is, from society’s point of view, a waste of resources.

Not all advertising poses a puzzle. Much of it is straightforward: it’s a way for sellers to inform potential buyers about what they have to offer (or, occasionally, for buyers to inform potential sellers about what they want). Nor is there much controversy about the economic usefulness of ads that provide information: the real estate ad that declares “sunny, charming, 2 br, 1 ba, a/c” tells you things you need to know (even if a few euphemisms are involved—

Fortunately, someone is looking out for consumers: providing misleading information in ads violates the Competition Act. For example, in 2012 the Competition Bureau sued Bell Canada, Rogers, Telus, and the Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association (CWTA) for misleading advertising. The investigation concluded that customers were given the false impression that certain texts and apps were free of charge, but these services were later charged to them. The Competition Bureau sought full refunds for customers and imposed $31 million in penalties ($10 million for each of the telecommunication companies involved and $1 million for the CWTA).

But if ads must be honest, what information is being conveyed when a TV actress proclaims the virtues of one or another toothpaste or a sports hero declares that some company’s batteries are better than those inside that pink mechanical rabbit? Surely nobody believes that the sports star is an expert on batteries—

Why are consumers influenced by ads that do not really provide any information about the product? One answer is that consumers are not as rational as economists typically assume. Perhaps consumers’ judgments, or even their tastes, can be influenced by things that economists think ought to be irrelevant, such as which company has hired the most charismatic celebrity to endorse its product. And there is surely some truth to this. As we learned in Chapter 9, consumer rationality is a useful working assumption; it is not an absolute truth.

However, another answer is that consumer response to advertising is not entirely irrational because ads can serve as indirect “signals” in a world where consumers don’t have good information about products. Suppose, to take a common example, that you need to avail yourself of some local service that you don’t use regularly—

The same principle may partly explain why ads feature celebrities. You don’t really believe that the supermodel prefers that watch; but the fact that the watch manufacturer is willing and able to pay her fee tells you that it is a major company that is likely to stand behind its product. According to this reasoning, an expensive advertisement serves to establish the quality of a firm’s products in the eyes of consumers.

The possibility that it is rational for consumers to respond to advertising also has some bearing on the question of whether advertising is a waste of resources. If ads only work by manipulating the weak-

Brand Names

You’ve been driving all day, and you decide that it’s time to find a place to sleep. On your right, you see a sign for the Bates Motel; on your left, you see a sign for a Travelodge, or a Best Western, or some other national chain. Which one do you choose?

Unless they were familiar with the area, most people would head for the chain. In fact, most motels in Canada are members of major chains; the same is true of most fast-food restaurants and many, if not most, stores in shopping malls.

Motel chains and fast-food restaurants are only one aspect of a broader phenomenon: the role of brand names, names owned by particular companies that differentiate their products in the minds of consumers. In many cases, a company’s brand name is the most important asset it possesses: clearly, Tim Hortons is worth far more than the sum of the coffee and baking equipment the company owns.

A brand name is a name owned by a particular firm that distinguishes its products from those of other firms.

In fact, companies often go to considerable lengths to defend their brand names, suing anyone else who uses them without permission. You may talk about blowing your nose on a kleenex or googling a person, but legally only Kleenex can call its facial tissue “Kleenex” and only Google can call its search engine “Google.”

As with advertising, with which they are closely linked, the social usefulness of brand names is a source of dispute. Does the preference of consumers for known brands reflect consumer irrationality? Or do brand names convey real information? That is, do brand names create unnecessary market power, or do they serve a real purpose?

As in the case of advertising, the answer is probably some of both. On one side, brand names often do create unjustified market power. Many consumers will pay more for brand-name goods in the supermarket even though consumer experts assure us that the cheaper store brands are equally good. Similarly, many common medicines, like acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, the key ingredient in Aspirin), are cheaper—with no loss of quality—in their generic form.

On the other side, for many products the brand name does convey information. A traveller arriving in a strange town can be sure of what awaits in a Holiday Inn or a Tim Hortons; a tired and hungry traveller may find these standardized products preferable to trying an independent hotel or restaurant that might be better—but might be worse.

In addition, brand names offer some assurance that the seller is engaged in repeated interaction with its customers and so has a reputation to protect. If a traveller eats a bad meal at a restaurant in a tourist trap and vows never to eat there again, the restaurant owner may not care, since the chance is small that the traveller will be in the same area again in the future. But if that traveller eats a bad meal at Tim Hortons and vows never to eat at a Tim Hortons again, that matters to the company. This gives Tim Hortons an incentive to provide consistent quality, thereby assuring travellers that quality controls are in place.

CAN ADVERTISING FOSTER IRRATIONALITY?

Advertising often serves a useful function. Among other things, it can make consumers aware of a wider range of alternatives, which leads to increased competition and lower prices. Indeed, in some cases the courts have viewed industry agreements not to advertise as violations of competition law. For example, in 2003 the RE/MAX family of real estate agents was found to be in violation of the Competition Act by prohibiting its agents from advertising and setting their own commission rates. RE/MAX settled the case with the Competition Bureau and agreed to allow its sales associates to set their commission rates independently and to advertise their rates.

Conversely, advertising sometimes creates product differentiation and market power where there is no real difference in the product. Consider, in particular, the spectacularly successful advertising campaign of Absolut vodka.

In Twenty Ads That Shook the World, James B. Twitchell puts it this way: “The pull of Absolut’s magnetic advertising is curious because the product itself is so bland. Vodka is aquavit, and aquavit is the most unsophisticated of alcohols. … No taste, no smell. … In fact, the Swedes, who make the stuff, rarely drink Absolut. They prefer cheaper brands such as Explorer, Renat Brannwinn, or Skane. That’s because Absolut can’t advertise in Sweden, where alcohol advertising is against the law.”

But here’s a metaphysical question: if Absolut doesn’t really taste any different from other brands, but advertising convinces consumers that they are getting a distinctive product, who are we to say that they aren’t? Isn’t distinctiveness in the mind of the beholder?

Quick Review

In industries with product differentiation, firms advertise in order to increase the demand for their products.

Advertising is not a waste of resources when it gives consumers useful information about products.

Advertising that simply touts a product is harder to explain. Either consumers are irrational, or expensive advertising communicates that the firm’s products are of high quality.

Some firms create brand names. As with advertising, the economic value of brand names can be ambiguous. They convey real information when they assure consumers of the quality of a product.

Check Your Understanding 15-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15-4

Question 15.6

In which of the following cases is advertising likely to be economically useful? Economically wasteful? Explain your answer.

Advertisements on the benefits of ASA

Advertisements for Bayer Aspirin, which is made with ASA

Advertisements on the benefits of drinking orange juice

Advertisements for Tropicana orange juice

Advertisements that state how long a plumber or an electrician has been in business

This is economically useful because such advertisements are likely to focus on the medical benefits of ASA.

This is economically wasteful because such advertisements are likely to focus on promoting Bayer Aspirin versus a rival’s ASA product. The two products are medically indistinguishable.

This is economically useful because such advertisements are likely to focus on the health and enjoyment benefits of orange juice.

This is economically wasteful because such advertisements are likely to focus on promoting Tropicana orange juice versus a rival’s product. The two are likely to be indistinguishable by consumers.

This is economically useful because the longevity of a business gives a potential customer information about its quality.

Question 15.7

Some industry analysts have stated that a successful brand name is like a barrier to entry. Explain the reasoning behind this statement.

A successful brand name indicates a desirable attribute, such as quality, to a potential buyer. So, other things equal—such as price—a firm with a successful brand name will achieve higher sales than a rival with a comparable product but without a successful brand name. This is likely to deter new firms from entering an industry in which an existing firm has a successful brand name.

Gillette Versus Schick: A Case of Razor Burn?

In early 2010, Schick introduced the Hydro system, its latest and most advanced razor, two months before the introduction of Gillette’s Pro-Glide, the latest upgrade in its Fusion line. According to reports at the time, Schick and Gillette would jointly spend over $250 million in international advertising for the two systems. It’s the latest round in a century-long rivalry between the two razor makers. Despite the rivalry, the razor business has been a profitable one; it has long been one of the priciest and highest profit margin sectors of nonfood packaged goods.

Schick and Gillette clearly hoped that the sophistication and features of their new shavers would appeal to customers. Hydro came with a lubricating gel dispenser and blade guards for smoother shaving, and a five-blade version came with a trimming blade. Schick considered the two versions of Hydro to offer both an upgrade and a value play to its existing product, the four-blade Quattro introduced in 2003. (A value play is an item that appeals to customers who are shopping on the basis of price.) And both versions of Hydro were priced below comparable versions of Gillette’s five-bladed Fusion and three-bladed Mach razors, as well as the Pro-Glide, which Gillette planned to price at 10 to 15 percent above its existing Fusion line.

This was not the first instance of a competitive razor launch. Back in 2003, Gillette and Schick went head-to-head when Gillette introduced its Mach 3 Turbo (an upgrade to its existing three-blade Mach 3), which delivered battery-powered pulses that Gillette said caused hair follicles to stand up, facilitating a closer shave. In 2003 Schick introduced the Quattro, the world’s first four-blade razor, which it called “unlike any other razor.”

Gillette is by far the larger company of the two, capturing about 70% of the Canadian razor market. Although Schick has a much smaller market share, many analysts believe it is the leader in innovation. “Schick appears to be grabbing the innovation lead and putting Gillette on the defensive,” says William Peoriello, an analyst at investment bank Morgan Stanley. “The roster of new razors from Schick is forcing Gillette to change the pace of its new product launches and appears likely to give Gillette its strongest competition ever.”

Some customers, though, are unimpressed with both companies’ offerings. In July 2010, the Wall Street Journal cited the example of Jeff Hagan, an investment banker, who searches out and stockpiles discontinued versions of Gillette’s Mach 3 razors and blades. It also profiled Steven Schimmel, the owner of an upscale pharmacy, who does a brisk business in old-fashioned, double-edge Gillette blades imported from a dealer in India. One disgruntled customer, Nick Meyers, gave up his four-blade Quattro because he got tired of trying to find drug store employees to unlock the blade case when he needed refills. “It’s easier to buy uranium,” said Meyers. “They’re so expensive, they have to keep them locked up, and that’s when I realized what a gimmick all of it is.”

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 15.8

What explains the complexity of today’s razors and the pace of innovation in their features?

What explains the complexity of today’s razors and the pace of innovation in their features?

Question 15.9

Why is the razor business so profitable? What explains the size of the advertising budgets of Schick and Gillette?

Why is the razor business so profitable? What explains the size of the advertising budgets of Schick and Gillette?

Question 15.10

What explains the reaction of customers like Hagan and Meyers? What dilemma do Schick and Gillette face in their decisions about whether to maintain their older, simpler razor models? What does this indicate about the value of the innovation in razors?

What explains the reaction of customers like Hagan and Meyers? What dilemma do Schick and Gillette face in their decisions about whether to maintain their older, simpler razor models? What does this indicate about the value of the innovation in razors?