17.1 Private Goods—And Others

What’s the difference between installing a new bathroom in a house and building a municipal sewage system? What’s the difference between growing wheat and fishing in the open ocean?

These aren’t trick questions. In each case there is a basic difference in the characteristics of the goods involved. Bathroom fixtures and wheat have the characteristics necessary to allow markets to work efficiently. Public sewage systems and fish in the sea do not.

Let’s look at these crucial characteristics and why they matter.

Characteristics of Goods

Goods like bathroom fixtures or wheat have two characteristics that, as we’ll soon see, are essential if a good is to be efficiently provided by a market economy.

A good is excludable if the supplier of that good can prevent people who do not pay from consuming it.

They are excludable: suppliers and owners of the good can prevent people who don’t pay from consuming it.

A good is rival in consumption if the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

They are rival in consumption: the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

A good that is both excludable and rival in consumption is a private good.

When a good is both excludable and rival in consumption, it is called a private good. Wheat is an example of a private good. It is excludable: the farmer can sell a bushel to one consumer without having to provide wheat to everyone in the county. And it is rival in consumption: if I eat bread baked with a farmer’s wheat, that wheat cannot be consumed by someone else.

When a good is nonexcludable, the supplier cannot prevent consumption by people who do not pay for it.

But not all goods possess these two characteristics. Some goods are nonexcludable—the supplier cannot prevent consumption of the good by people who do not pay for it. Fire protection is one example: a fire department that puts out fires before they spread protects the whole city, not just people who have made contributions to the Firefighters’ Benevolent Fund. An improved environment is another: the city of London couldn’t have ended the Great Stink for some residents while leaving the river Thames foul for others.

A good is nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time.

Nor are all goods rival in consumption. Goods are nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time. TV programs are nonrival in consumption: your decision to watch a show does not prevent other people from watching the same show.

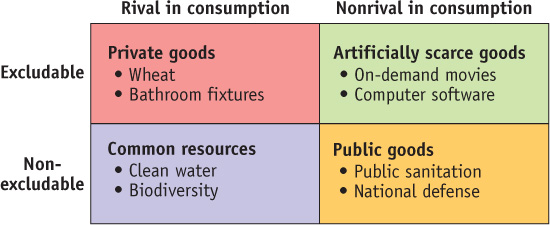

Because goods can be either excludable or nonexcludable, rival or nonrival in consumption, there are four types of goods, illustrated by the matrix in Figure 17-1:

Private goods, which are excludable and rival in consumption, like wheat

Public goods, which are nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption, like a public sewer system

Common resources, which are nonexcludable but rival in consumption, like clean water in a river

Artificially scarce goods, which are excludable but nonrival in consumption, like on-

demand movies on CinemaNow

There are, of course, many other characteristics that distinguish between types of goods—

Why Markets Can Supply Only Private Goods Efficiently

As we learned in earlier chapters, markets are typically the best means for a society to deliver goods and services to its members; that is, markets are efficient except in the case of the well-defined problems of market power, externalities, or other instances of market failure. But there is yet another condition that must be met, one rooted in the nature of the good itself: markets cannot supply goods and services efficiently unless they are private goods—excludable and rival in consumption.

To see why excludability is crucial, suppose that a farmer had only two choices: either produce no wheat or provide a bushel of wheat to every resident of the county who wants it, whether or not that resident pays for it. It seems unlikely that anyone would grow wheat under those conditions.

Yet the operator of a municipal sewage system faces pretty much the same problem as our hypothetical farmer. A sewage system makes the whole city cleaner and healthier—but that benefit accrues to all the city’s residents, whether or not they pay the system operator. That’s why no private entrepreneur came forward with a plan to end London’s Great Stink.

The general point is that if a good is nonexcludable, self-interested consumers won’t be willing to pay for it—they will take a “free ride” on anyone who does pay. So there is a free-rider problem. Examples of the free-rider problem are familiar from daily life. One example you may have encountered happens when students are required to do a group project. There is often a tendency of some group members to shirk, relying on others in the group to get the work done. The shirkers free-ride on someone else’s effort.

Goods that are nonexcludable suffer from the free-rider problem: many individuals are unwilling to pay for their own consumption and instead will take a “free ride” on anyone who does pay.

Because of the free-rider problem, the forces of self-interest alone do not lead to an efficient level of production for a nonexcludable good. Even though consumers would benefit from increased production of the good, no one individual is willing to pay for more, and so no producer is willing to supply it. The result is that nonexcludable goods suffer from inefficiently low production in a market economy. In fact, in the face of the free-rider problem, self-interest may not ensure that any amount of the good—let alone the efficient quantity—is produced.

MARGINAL COST OF WHAT EXACTLY?

In the case of a good that is nonrival in consumption, it’s easy to confuse the marginal cost of producing a unit of the good with the marginal cost of allowing a unit of the good to be consumed. For example, CinemaNow incurs a marginal cost in making a movie available to its subscribers that is equal to the cost of the resources it uses to produce and broadcast that movie. However, once that movie is being broadcast, no marginal cost is incurred by letting an additional family watch it. In other words, no costly resources are “used up” when one more family consumes a movie that has already been produced and is being broadcast.

This complication does not arise, however, when a good is rival in consumption. In that case, the resources used to produce a unit of the good are “used up” by a person’s consumption of it—they are no longer available to satisfy someone else’s consumption. So when a good is rival in consumption, the marginal cost to society of allowing an individual to consume a unit is equal to the resource cost of producing that unit—that is, equal to the marginal cost of producing it.

Goods that are excludable and nonrival in consumption, like on-demand movies, suffer from a different kind of inefficiency. As long as a good is excludable, it is possible to earn a profit by making it available only to those who pay. Therefore, producers are willing to supply an excludable good. But the marginal cost of letting an additional viewer watch an on-demand movie is zero because it is nonrival in consumption. So the efficient price to the consumer is also zero—or, to put it another way, individuals should watch movies up to the point where their marginal benefit is zero.

But if CinemaNow actually charges viewers $4, viewers will consume the good only up to the point where their marginal benefit is $4. When consumers must pay a price greater than zero for a good that is nonrival in consumption, the price they pay is higher than the marginal cost of allowing them to consume that good, which is zero. So in a market economy goods that are nonrival in consumption suffer from inefficiently low consumption.

Now we can see why private goods are the only goods that can be efficiently produced and consumed in a competitive market. (That is, a private good will be efficiently produced and consumed in a market free of market power, externalities, or other instances of market failure.) Because private goods are excludable, producers can charge for them and so have an incentive to produce them. And because they are also rival in consumption, it is efficient for consumers to pay a positive price—a price equal to the marginal cost of production. If one or both of these characteristics are lacking, a market economy will not lead to efficient production and consumption of the good.

Fortunately for the market system, most goods are private goods. Food, clothing, shelter, and most other desirable things in life are excludable and rival in consumption, so markets can provide us with most things. Yet there are crucial goods that don’t meet these criteria—and in most cases, that means that the government must step in.

FROM MAYHEM TO RENAISSANCE

Life during the European Middle Ages—from approximately 1100 to 1500—was difficult and dangerous, with high rates of violent crime, banditry, and war casualties. According to researchers, murder rates in Europe in 1200 were 30 to 40 per 100 000 people. But by 1500 the rate had been halved to around 20 per 100 000; today, it is less than 1 per 100 000. What accounts for the sharp decrease in mayhem over the last 900 years?

Think public goods, as the history of medieval Italian city-states illustrates.

Starting around the year 900 in Venice and 1100 in other city-states like Milan and Florence, citizens began to organize and create institutions for protection. In Venice, citizens built a defensive fleet to battle the pirates and other marauders who regularly attacked them. Other city-states built strong defensive walls to encircle their cities and also paid defensive militias. Institutions were created to maintain law and order: cadres of guards, watchmen, and magistrates were hired; courthouses and jails were built.

As a result, trade, commerce, and banking were able to flourish, as well as literacy, numeracy, and the arts. By 1300, the leading cities of Venice, Milan, and Florence had each grown to over 100 000 people. As resources and the standard of living increased, the rate of violent deaths diminished.

For example, the Republic of Venice was known as La Serenissima—the most serene one—because of its enlightened governance, overseen by a council of leading citizens. Owing to its stability, diplomatic prowess, and prodigious fleet of vessels, Venice became enormously wealthy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Also through stability, high literacy, and numeracy, Florence became the banking centre of Italy. During the fifteenth century it was ruled by the Medici, an immensely wealthy banking family. And it was the patronage of the Medici to artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo that ushered in the Renaissance.

So Western Europe was able to move from mayhem to Renaissance through the creation of public goods like good governance and defence—goods that benefitted everyone and could not be diminished by any one person’s use.

Quick Review

Goods can be classified according to two attributes: whether they are excludable and whether they are rival in consumption.

Goods that are both excludable and rival in consumption are private goods. Private goods can be efficiently produced and consumed in a competitive market.

When goods are nonexcludable, there is a free-rider problem: consumers will not pay producers, leading to inefficiently low production.

When goods are nonrival in consumption, the efficient price for consumption is zero. But if a positive price is charged to compensate producers for the cost of production, the result is inefficiently low consumption.

Check Your Understanding 17-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 17-1

Question 17.1

Classify each of the following goods according to whether they are excludable and whether they are rival in consumption. What kind of good is each?

Use of a public space such as a park

A cheese burrito

Information from a website that is password-protected

Publicly announced information on the path of an incoming hurricane

Use of a public park is nonexcludable, but it may or may not be rival in consumption, depending on the circumstances. For example, if both you and I use the park for jogging, then your use will not prevent my use—use of the park is nonrival in consumption. In this case the public park is a public good. But use of the park is rival in consumption if there are many people trying to use the jogging path at the same time or when my use of the public tennis court prevents your use of the same court. In this case the public park is a common resource.

A cheese burrito is both excludable and rival in consumption. Hence it is a private good.

Information from a password-protected website is excludable but nonrival in consumption (if we assume the website servers are uncongested). So it is an artificially scarce good.

Publicly announced information on the path of an incoming hurricane is nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption. So it is a public good.

Question 17.2

Which of the goods in Question 1 will be provided by a competitive market? Which will not be? Explain your answer.

A private producer will supply only a good that is excludable; otherwise, the producer won’t be able to charge a price for it that covers the costs of production. So a private producer would be willing to supply a cheese burrito and information from a password-protected website but unwilling to supply a public park or publicly announced information about an incoming hurricane.