17.3 Common Resources

A common resource is nonexcludable and rival in consumption: you can’t stop me from consuming the good, and more consumption by me means less of the good available for you.

A common resource is a good that is nonexcludable but is rival in consumption. An example is the stock of salmon in a limited fishing area, like the fisheries off the coast of British Columbia. Traditionally, anyone who had a boat could go out to sea and catch salmon—

Other examples of common resources are clean air and water as well as the diversity of animal and plant species on the planet (biodiversity). In each of these cases the fact that the good, though rival in consumption, is nonexcludable poses a serious problem.

The Problem of Overuse

Common resources left to the market suffer from overuse: individuals ignore the fact that their use depletes the amount of the resource remaining for others.

Because common resources are nonexcludable, individuals cannot be charged for their use. Yet because they are rival in consumption, an individual who uses a unit depletes the resource by making that unit unavailable to others. As a result, a common resource is subject to overuse: an individual will continue to use it until his or her marginal benefit of its use is equal to his or her own individual marginal cost, ignoring the cost that this action inflicts on society as a whole. As we will see shortly, the problem of overuse of a common resource is similar to a problem we studied in Chapter 16: the problem of a good that generates a negative externality, such as pollution-

Fishing is a classic example of a common resource. In heavily fished waters, fishing by one person—

In the case of a common resource, the marginal social cost of an individual’s use of that resource is higher than his or her individual marginal cost, the cost of using an additional unit of the good.

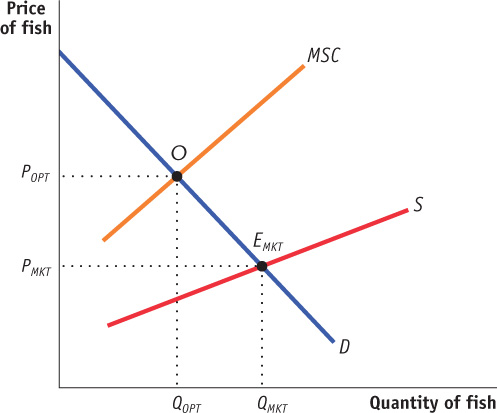

Figure 17-3 illustrates the point. It shows the demand curve for fish, which measures the marginal benefit of fish—

PUTTING A CAP ON BOTTLED WATER

British Columbians are fiercely proud of the pristine beauty and clean environment of their province. But like the rest of Canada, they are somewhat addicted to consuming bottled water. In 2012, retail sales of bottled water reached 2.3 billion litres, generating revenue of $2.3 billion. According to Statistics Canada’s 2011 Households and the Environment Survey, about 22% of Canadian households claimed they primarily drank bottled water at home.2 According to the Canadian Bottled Water Association, more than 95% of bottled water sold in Canada is from a natural source (spring or mineral water), with the remaining originating from a municipal source (i.e., filtered tap water).

Spring water used as drinking water is a valuable commodity; but having private companies extract this valuable resource at little or no cost has Canadians concerned that the bottled water industry is “privatizing” water at the expense of the public. Could companies be overdrawing the groundwater, leaving too little water for future generations? To address these and other concerns, the bottled water industry is subject to both federal and provincial regulations.

The federal government treats bottled water as a food product and regulates bottled water under the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations, which set the requirements on quality, composition, and labelling of the product. Provincial governments are responsible for approving water sources, granting permits, and setting fees, rates of production, watershed protection, and drilling practices. All of these measures are aimed at making the use of this common resource safe and sustainable.

Over the past twenty years many Canadians have petitioned the government to either start imposing royalties for the extraction of groundwater or to raise existing royalty rates—

To put this into perspective, consider the Nestlé Canada plant in Hope, B.C. that bottles an estimated 320 million litres of groundwater per year. If the groundwater fees are set equal to the 2013 royalty rate of $0.85 per 1000 cubic metres that industrial users are charged for surface water, after the one-

As we noted, there is a close parallel between the problem of managing a common resource and the problem posed by negative externalities. In the case of an activity that generates a negative externality, the marginal social cost of production is greater than the industry’s marginal cost of production, the difference being the marginal external cost imposed on society. Here, the loss to society arising from a fisher’s depletion of the common resource plays the same role as the external cost plays when there is a negative externality. In fact, many negative externalities (such as pollution) can be thought of as involving common resources (such as clean air).

The Efficient Use and Maintenance of a Common Resource

Because common resources pose problems similar to those created by negative externalities, the solutions are also similar. To ensure efficient use of a common resource, society must find a way of getting individual users of the resource to take into account the costs they impose on other users. This is basically the same principle as that of getting individuals to internalize a negative externality that arises from their actions.

There are three fundamental ways to induce people who use common resources to internalize the costs they impose on others.

Tax or otherwise regulate the use of the common resource

Create a system of tradable licences for the right to use the common resource

Make the common resource excludable and assign property rights to some individuals

Like activities that generate negative externalities, use of a common resource can be reduced to the efficient quantity by imposing a Pigouvian tax. For example, some countries have imposed “congestion charges” on those who drive during rush hour, in effect charging them for use of the common resource of highway space. Likewise, visitors to national and provincial parks must pay a fee, and the number of visitors to any one park is restricted.

A second way to correct the problem of overuse is to create a system of tradable licences for the use of the common resource much like the systems designed to address negative externalities. The policy-maker issues the number of licences that corresponds to the efficient level of use of the good. Making the licences tradable ensures that the right to use the good is allocated efficiently—that is, those who end up using the good (those willing to pay the most for a licence) are those who gain the most from its use.

But when it comes to common resources, often the most natural solution is simply to assign property rights. At a fundamental level, common resources are subject to overuse because nobody owns them. The essence of ownership of a good—the property right over the good—is that you can limit who can and cannot use the good as well as how much of it can be used. When a good is nonexcludable, in a very real sense no one owns it because a property right cannot be enforced—and consequently no one has an incentive to use it efficiently. So one way to correct the problem of overuse is to make the good excludable and assign property rights over it to someone. The good now has an owner who has an incentive to protect the value of the good—to use it efficiently rather than overuse it.

As the upcoming Economics in Action shows, a system of tradable licences, called individual transferable quotas or ITQs, has been a successful strategy in some fisheries.

A TALE OF TWO FISHERIES

When John Cabot reached Newfoundland in 1497 the seas were so teeming with cod that they impeded the passage of his ship. And for centuries in Newfoundland and Labrador, “cod was king,” providing tens of thousands of jobs and feeding the world. But all this came to an end in 1992 when the federal government declared a moratorium on all commercial cod fishing in Atlantic Canada because of overfishing (cod had been overfished almost to the point of extinction). The government hoped that, by shutting down the industry, cod stocks would be able to eventually recover. More than 20 years later, the people of Newfoundland and Labrador are still waiting for the moratorium to be lifted.

Sadly, overfishing is not unique to the cod fishery and because of it the world’s oceans are in serious trouble. According to a 2013 report by the International Program on the State of the Oceans, there is an imminent risk of widespread extinctions of multiple species of fish. In Europe, 30% of the fish stocks are in danger of collapse. In the North Sea, 93% of cod are fished before they can breed. And bluefin tuna, a favourite in Japanese sushi, are in danger of imminent extinction.

The decline of fishing stocks has worsened as fishers trawl in deeper waters with their very large nets to catch the remaining fish, unintentionally killing many other marine animals in the process.

The fishing industry is in crisis, too, as fishers’ incomes decline and they are compelled to fish for longer periods of time and in more dangerous waters in order to make a living.

But there is hope that individual transferable quotas, or ITQs, may provide a solution to both crises. Under an ITQ scheme, a fisher receives a licence entitling him or her to catch an annual quota within a given fishing ground. The ITQ is given for a long period of time, sometimes indefinitely. Because it is transferable, the owner can sell or lease it.

Researchers who analyzed 121 established ITQ schemes around the world concluded that ITQs can help reverse the collapse of fisheries because each ITQ holder now has a financial interest in the long-term maintenance of his or her particular fishery.

ITQ schemes (also called catch-share schemes) are common in New Zealand, Australia, Iceland, and increasingly in Canada and the United States. Fortunately for Canada’s East Coast, thanks to a successful ITQ scheme, there remains a profitable and vibrant lobster fishery that provides direct employment for 30 000 to 35 000 people with annual exports of more than $1 billion. In an attempt to protect the industry, a tradable licence system was established in 1967. To legally set a lobster trap, you must have a licence and only a limited number of licences have been issued. A licence could easily cost more than $200 000 (plus annual government charges). At first Atlantic lobster fishers were skeptical of a system that limited their fishing. But they now support the system because it sustains the value of their licences and protects their livelihood by attempting to limit overfishing. Without a system in place to limit how much lobster can be caught, the Atlantic lobster fishery could have gone the way of the cod fishery.

Quick Review

A common resource is rival in consumption but nonexcludable.

The problem with common resources is overuse: a user depletes the amount of the common resource available to others but does not take this cost into account when deciding how much to use the common resource.

Like negative externalities, a common resource can be efficiently managed by Pigouvian taxes, by the creation of a system of tradable licences for its use, or by making it excludable and assigning property rights.

Check Your Understanding 17-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 17-3

Question 17.4

Rocky Mountain Forest is Crown land (government-owned) from which private citizens were allowed in the past to harvest as much timber as they wanted free of charge. State in economic terms why this is problematic from society’s point of view.

When individuals are allowed to harvest freely, Crown land becomes a common resource, and individuals will overuse it—they will harvest more trees than is efficient. In economic terms, the marginal social cost of harvesting a tree is greater than a private logger’s individual marginal cost.

Question 17.5

You are an advisor to the Minister of Natural Resources and have been instructed to come up with ways to preserve the forest for the general public. Name three different methods you could use to maintain the efficient level of tree harvesting and explain how each would work. For each method, what information would you need to know in order to achieve an efficient outcome?

The three methods consistent with economic theory are (i) Pigouvian taxes, (ii) a system of tradable licences, and (iii) allocation of property rights.

Pigouvian taxes. You would enforce a tax on loggers that equals the difference between the marginal social cost and the individual marginal cost of logging a tree at the socially efficient harvest amount. In order to do this, you must know the marginal social cost schedule and the individual marginal cost schedule.

System of tradable licences. You would issue tradable licences, setting the total number of trees harvested equal to the socially efficient harvest number. The market that arises in these licences will allocate the right to log efficiently when loggers differ in their costs of logging: licences will be purchased by those who have a relatively lower cost of logging. The market price of a licence will be equal to the difference between the marginal social cost and the individual marginal cost of logging a tree at the socially efficient harvest amount. In order to implement this level, you need to know the socially efficient harvest amount.

Allocation of property rights. Here you would sell or give the forest to a private party. This party will have the right to exclude others from harvesting trees. Harvesting is now a private good—it is excludable and rival in consumption. As a result, there is no longer any divergence between social and private costs, and the private party will harvest the efficient level of trees. You need no additional information to use this method.