18.2 The Welfare State in Canada

The welfare state in Canada consists of three huge programs (health care, social security/old age security, and child care benefits) and a number of smaller programs. Table 18-3 shows one useful way to categorize the major welfare state programs in Canada.

The spending on these welfare state programs varies and comes from different levels of governments. For example, in the 2012–2013 fiscal year, governments in Canada spent $40.255 billion on Old Age Security benefits, $12.975 billion on family allowance/children’s benefits, and $17.099 billion on Employment Insurance benefits. In 2012, pension benefits payments from the CPP/QPP reached $46.22 billion, bringing total government spending on social benefits to more than $140 billion. Last but not least, the largest component in Canada’s welfare state program is the provision of health care services; doctors, hospitals,prescription medicine, and other specialized services, which cost $221.2 billion in 2013 for all levels of government.4

Table 18-3 distinguishes between programs that are means-

A means-tested program is a program available only to individuals or families whose incomes fall below a certain level.

An in-kind benefit is a benefit given in the form of goods or services.

Table 18-3 also distinguishes between programs that provide monetary transfers that beneficiaries can spend as they choose and those that provide in-kind benefits, which are given in the form of goods or services rather than money. The largest in-

Means-Tested Programs

When people speak of welfare, they are often referring to monetary aid to poor families. The main source of such monetary aid in Canada is social services. Social services programs include social assistance, workers’ compensation benefits, veterans’ benefits, and other social services. These programs are exclusively for low-

Old Age Security (OAS) is a major part of Canada’s public pension system. The OAS has two parts: the OAS pension, which is a monthly payment to Canadians who are 65 or above; and the OAS benefits (Guarantee Income Supplement, Allowance, and Allowance for the Survivor, which are additional payments to low-

A negative income tax is a program that supplements the income of low-

Economists use the term negative income tax for a program that supplements the earnings of low-

Non-Means-Tested Programs

Non-

The CPP was established in 1965 by the Pearson government with the goal of providing financial security in the case of retirement, disability, or death. Quebec is the only province to have opted out of the CPP and instead has its own public pension (QPP). CPP/QPP was made mandatory to force workers to save some of their current income for retirement. The goal is to overcome the shortsightedness of workers, especially younger Canadians, who do not save enough money to support themselves after retirement.

CPP/QPP initially had a “pay-

Like CPP/QPP, the provision of free (and mandatory) education up to Grade 12 in Canada also helps to alleviate the problem of shortsightedness—

Employment Insurance (EI), although normally a smaller portion of government transfers than social pensions, is another key social insurance program. EI provides qualifying workers who lose their jobs with up to 55% of their insured income up to a yearly maximum insurable amount—

The Effects of the Welfare State on Poverty and Inequality

Because the people who receive government transfers tend to be different from those who are taxed to pay for those transfers, the welfare state in Canada has the effect of redistributing income from some people to others. Each year Statistics Canada computes the amount and share of government transfers provided to the Canadians.

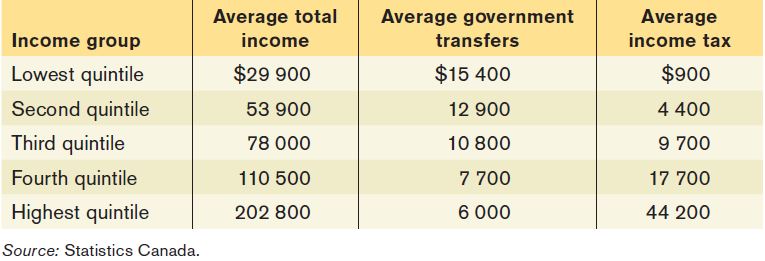

Table 18-4 shows the average total income, average government transfers received, and average income tax paid by families in different income groups in 2011. It is not surprising that there is an inverse relationship between income and average government transfers received. As a household’s income rises, it will be less reliant on government assistance, so the amount of government transfers received falls. Given the progressive tax system in Canada, as income rises, tax liabilities also increase because the ability to pay increases.

According to Table 18-4, the poorest 20% of Canadian households receive about 30% of the total government transfers and only pay about 1% of the total income tax. On the other hand, the richest 20% of Canadian households receive the smallest share of government transfers and pay more than 57% of the total income tax. This is a clear indication that the design of the welfare state programs and tax system in Canada is aimed at helping the poor and redistributing income from the rich to the poor.

LULA LESSENS INEQUALITY

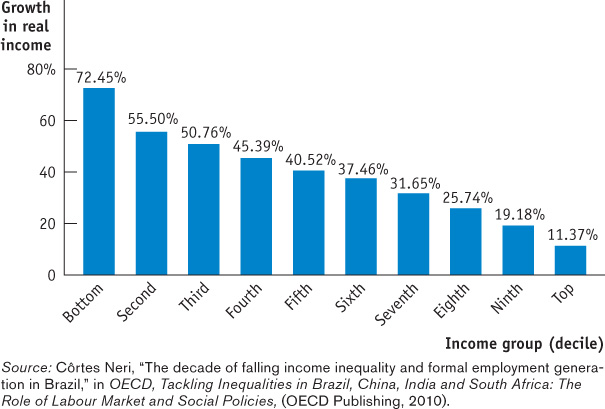

Brazil was one of the world’s most unequal societies in 2002, the year Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, universally known simply as Lula, was elected president. It was still one of the world’s most unequal societies in 2010, when he handed the reins over to Dilma Roussef, his successor. But by 2010 Brazil was less unequal, and poverty was sharply lower. And Brazil’s fight against poverty and inequality has become an international role model.

The numbers are striking. Figure 18-4 shows percentage changes in real income for different deciles (tenths) of the Brazilian population from 2001 to 2008. As you can see, there were huge gains for the poorest 10%, and the overall movement was clearly toward greater equality.

How did the Brazilians do it? One key factor was a new program known as Bolsa Familia (family grant). This program—modelled on a similar program in Mexico, but carried out on an even larger scale—offers what are known as “conditional cash transfers”: payments that are available to poor families provided they meet certain requirements designed to help break the cycle of poverty. In particular, to get their allowances, families must keep their children in school and go for regular medical checkups, and mothers must attend workshops on subjects such as nutrition and disease prevention. The payments go to women rather than men because they are the most likely to spend the money on their families.

As of 2010, Bolsa Familia covered 50 million Brazilians, a quarter of the population. The payments don’t sound like much by Canadian standards: a monthly stipend of about $13 to poor families for each child age 15 or younger attending school, slightly higher payments for older children still in school, and a basic benefit of about $40 for families in extreme poverty. But Brazil’s poor are very poor indeed, and these sums were enough to make a huge difference in their incomes.

The success of Bolsa Familia has led to the establishment of similar programs in many countries, including the United States: a small pilot program along similar lines has been established in New York City.

Quick Review

Means-tested programs are designed to reduce poverty, but non-means-tested programs do so as well. Programs are classified according to whether they provide monetary or in-kind benefits.

A negative income tax is a program that supplements the earnings of low-income working families. Though several countries use a negative income tax program, Canada does not.

Check Your Understanding 18-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 18-2

Question 18.5

Explain how the negative income tax avoids the disincentive to work that characterizes social welfare programs that simply give benefits based on low income.

A negative income tax applies only to those workers who earn income; over a certain range of incomes, the more a worker earns, the higher the credit received. A person who earns no income receives no income tax credit. By contrast, social welfare programs that pay individuals based solely on low income still make those payments even if the individual does not work at all; once the individual earns a certain amount of income, these programs discontinue payments. As a result, such programs contain an incentive not to work and earn income, since earning more than a certain amount makes individuals ineligible for their benefits. The negative income tax, however, provides an incentive to work and earn income because its payments increase the more an individual works.

Question 18.6

According to Table 18-4, what effect does the Canadian welfare state have on the overall poverty rate?

According to the data in Table 18-4, the Canadian welfare state reduces the poverty rate. It does so by sending significantly more transfers to low-income families than it takes via income taxes. Families in the first three quintiles receive more transfer than they pay in income taxes. The poorest 20% of Canadian households receive about 30% of total government transfers and only pay about 1% of the total income tax.