18.3 The Economics of Health Care

Alarge part of the welfare state, in Canada and in other wealthy countries, is devoted to paying for health care. In most wealthy countries, the government pays between 70% and 80% of all medical costs of its citizens and permanent residents. In Canada the public sector picks up 70% of all health care costs—

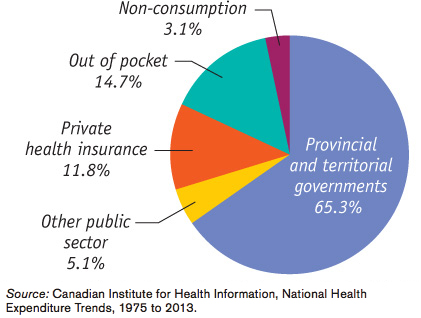

Figure 18-5 shows who paid for Canadian health care in 2011. Only 14.7% of health care spending was expenses “out of pocket”—that is, paid directly by individuals. Most health care spending, 70.4%, was paid for by the public sector—

Insurance of some form or another paid for the majority of all Canadian health care costs. To understand why, we need to examine the special economics of health care.

The Need for Health Insurance

In 2013, Canadian personal health care expenses were about $6000 per person—

Is it possible to predict who will have high medical costs? To a limited extent, yes: there are broad patterns to illness. For example, the elderly are more likely to need expensive surgery and/or drugs than the young. But the fact is that anyone can suddenly find himself or herself needing very expensive medical treatment, costing many thousands of dollars in a very short time—

Under private health insurance, each member of a large pool of individuals pays a fixed amount annually to a private company that agrees to pay most of the medical expenses of the pool’s members.

Private Health Insurance Market economies have an answer to this problem: health insurance. Under private health insurance, each member of a large pool of individuals agrees to pay a fixed amount annually (called a premium) into a common fund (or pool) that is managed by a private company, which then pays most of the medical expenses of the pool’s members. Although members must pay fees even in years in which they don’t have large medical expenses, they benefit from the reduction in risk: if they do turn out to have high medical costs, the pool will take care of those expenses.

There are, however, inherent problems with the market for private health insurance. These problems arise from the fact that medical expenses, although basically unpredictable, aren’t completely unpredictable. That is, people often have some idea whether or not they are likely to face large medical bills over the next few years. This creates a serious problem for private health insurance companies.

Suppose that an insurance company offers a “one-

If all potential customers had an equal risk of incurring high medical expenses for the year, this might be a workable business proposition. In reality, however, people often have very different risks of facing high medical expenses—

As a result, some healthy people are likely to take their chances and go without insurance. This would make the insurance company’s average customer less healthy than the average Canadian. This raises the medical bills the company will have to pay and raises the company’s costs per customer. That is, the insurance company would face a problem called adverse selection, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 20. Because of adverse selection, a company that offers health insurance to everyone at a price reflecting average medical costs of the general population, and that gives people the freedom to decline coverage, would find itself losing a lot of money.

A CALIFORNIA DEATH SPIRAL

At the beginning of 2006, 116 000 workers at more than 6000 California small businesses received health coverage from PacAdvantage, a “purchasing pool” that offered employees at member businesses a choice of insurance plans. The idea behind PacAdvantage, which was founded in 1992, was that by banding together, small businesses could get better deals on employee health insurance.

But only a few months later, in August 2006, PacAdvantage announced that it was closing up shop because it could no longer find insurance companies willing to offer plans to its members.

What happened? It was the adverse selection death spiral. PacAdvantage offered the same policies to everyone, regardless of their prior health history. But employees didn’t have to get insurance from PacAdvantage—

The insurance company could respond by charging more—

This description of the problems with health insurance might lead you to believe that private health insurance can’t work. In fact, however, most working Canadians do have some private health insurance that supplements the public coverage available to all. Insurance companies are able, to some extent, to overcome the problem of adverse selection two ways: by carefully screening people who apply for coverage and through employment-

Employment-

There’s another reason employment-

In spite of this subsidy, however, many working Canadians don’t receive employment-

Government Health Insurance

Canada operates a publicly funded, privately provided, universal, comprehensive, accessible and portable, single-

A single-payer system is a health care system in which the government is the principal payer of medical bills funded through taxes.

Under public health insurance, sometimes called publicly funded health insurance, each member of the public (citizens and permanent residents) qualifies for free access to certain health care services, which are paid for by the government. Canada’s public health care system is a single-payer system with the government acting as the single insurer and paying the entire cost of all medically insured health care services. Although the public does not directly face any payment, this health care spending is financed through taxes, in some cases including special levies geared toward collecting funding specifically for health care.

Canada’s health care system is administered by the provinces and territories according to the constitution. Nevertheless, the federal government plays a key role in the public provision of health care: it sends transfer payments to provinces to help cover health care costs. The Canada Health Act, which was unanimously enacted by Parliament in 1984, established five national principles as to how the provision of public health care should operate (otherwise federal transfer payments may be withheld).5 As described by Parliament these five national principles are:

Universality, meaning the public health care insurance must be provided to all Canadians.

Comprehensiveness, meaning that all medically necessary hospital and doctor services are covered by public health insurance.

Accessibility, meaning that financial or other barriers to the provision of publicly funded health services are discouraged, so that health services are available to all Canadians when they need them.

Portability, meaning that all Canadians are covered under public health care insurance, even when they travel internationally or move within Canada.

Public administration, which requires provincial and territorial health care insurance plans be managed by a public agency on a not-

for- profit basis.

According to the federal government, there are two overarching objectives of federal health care policy: (1) to ensure that every Canadian has timely access to all medically necessary health services regardless of their ability to pay for those services; and (2) to ensure that no Canadian suffers undue financial hardship as a result of having to pay health care bills.

While publicly funded, Canada’s health care is largely provided by private doctors and not-

For decades, Canada’s health care was privately funded, resulting in access to care based on ability to pay. But in 1947 Saskatchewan introduced Canada’s first publicly funded health insurance plan covering hospital services. In 1956 the federal government offered to share the costs with any province setting up a provincially funded health insurance plan. By 1961, all provinces and territories had signed agreements with the federal government and had set up provincial health insurance plans covering hospital care that qualified for federal cost sharing. The public health care system has since evolved into a provincial or territorial provision of many doctor and hospital health care services to all Canadians, plus a prescription drug benefit. These drug benefit plans are generally targeted to seniors, recipients of social assistance, and individuals with illnesses or conditions that are associated with high drug costs. All other Canadians have to pay for prescription drugs either out of their own pockets or via private supplemental health insurance. The same goes for any non-

Health Care in Other Countries

Health care is one area in which Canada is very different from the United States. In fact, when it comes to health care the United States is very different from most other wealthy countries in three distinct ways. First, the United States relies much more on private health insurance than any other wealthy country does. Second, they spend much more on health care per person. Third, they’re the only wealthy nation in which large numbers of people lack health insurance.

The United States government runs three health insurance programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and military health care. Medicare covers hospitalizations and some other medical costs. It is financed by payroll taxes and is available to all Americans 65 and older, regardless of their income and wealth. Medicaid is a means-

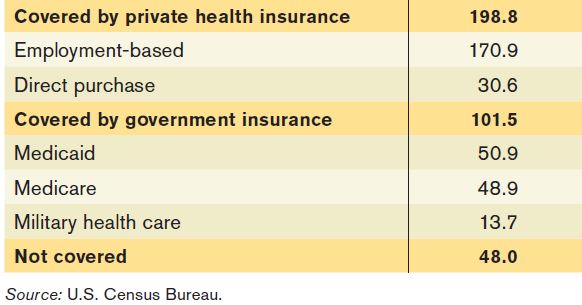

Table 18-5 shows the breakdown of health insurance coverage across the U.S. population in 2012. A majority of Americans—

So the U.S. health care system offers a mix of private insurance, mainly from employers, and public insurance of various forms. Most Americans have health insurance either from private insurance companies or through various forms of government insurance. However, in 2012 almost 48 million Americans, 15.4% of the population, had no health insurance at all.

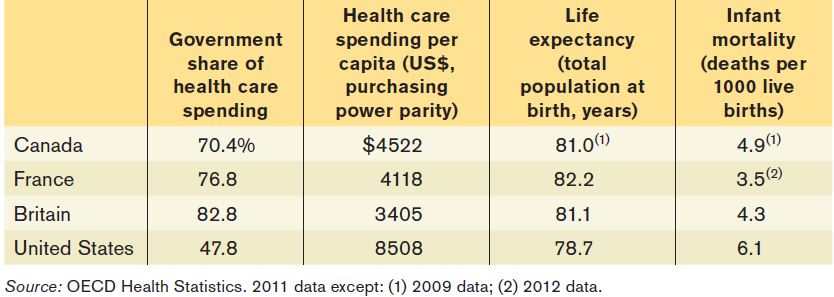

Table 18-6 compares four wealthy countries: Canada, France, Britain, and the United States. The United States is the only one of the four countries that relies on private health insurance to cover most people; as a result, it’s the only one in which private spending on health care is (slightly) larger than public spending on health care.

As previously mentioned, Canadian doctors are generally not employed directly by the government, and hospitals, although they are not-

All three non-

Surveys of patients seem to suggest that there are no significant differences in the quality of care received by patients in Canada, Europe, and the United States. And as Table 18-6 shows, the United States does considerably worse than other advanced countries in terms of basic measures such as life expectancy and infant mortality, although their poor performance on these measures may have causes other than the quality of medical care—

So why does the United States spend so much more on health care than other wealthy countries do? Some of the disparity is the result of higher doctors’ salaries, but most studies suggest that this is a secondary factor. Another possibility is that Americans are getting better care than their counterparts abroad, but statistics don’t back up this claim.

However, the most likely explanation is that the U.S. system suffers from serious inefficiencies that other countries manage to avoid. Critics of the U.S. system emphasize the system’s reliance on private insurance companies, which expend resources on such activities as marketing and trying to identify and weed out high-

The 2010 U.S. Health Care Reform (“ObamaCare”)

However one rates the past performance of the U.S. health care system, by 2009 it was clearly in trouble. The root of the problem was the rising cost of health insurance, both private and public.

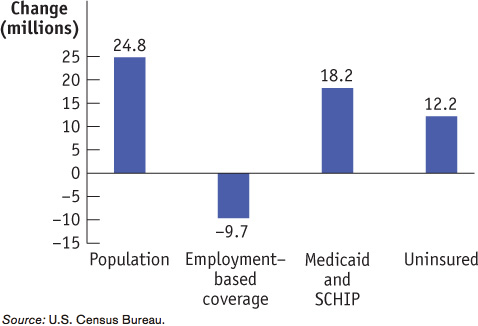

An immediate problem was that the cost of private insurance had been rising much faster than incomes. From 1999 to 2009, the average premiums for employment-

As a result of these rising costs, employment-

At the same time, as U.S. private health insurance was faltering and the ranks of the uninsured increased, American public health insurance was coming under increasing financial strain. Partly this was because Medicaid and other U.S. government programs covered more people than in the past. Mainly, however, it was because the cost per beneficiary of government health insurance, like the cost per beneficiary of private insurance, had been rising rapidly.

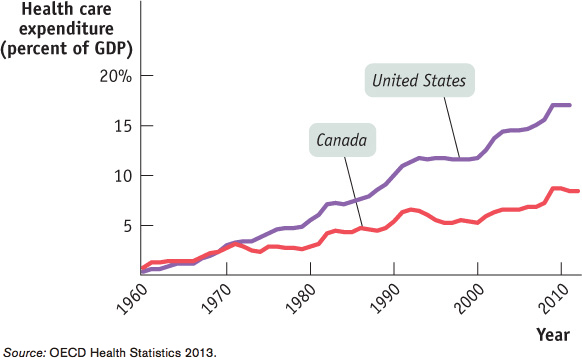

What’s behind these rising costs? Figure 18-7 shows overall Canadian and U.S. spending on health care as a percentage of GDP, a measure of the nation’s total income, since the 1960s. As you can see, U.S. health spending as a share of income rose about 350% between 1960 and 2011; this increase in spending explains why health insurance became more expensive in the United States. While similar trends can be observed in other countries, in Canada health care spending as a percentage of GDP rose by just over 200% during this same period.

The consensus of health experts is that the increase in health spending is a result of medical progress. As medical science progresses, conditions that could not be treated in the past become treatable, but often only at great expense. Both private insurers and government programs feel compelled to cover the new procedures—

In the United States, the combination of a rising number of uninsured and rising costs led to many calls for health care reform. And in 2010 the U.S. Congress passed comprehensive health care reform legislation, officially known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, or ACA for short), but often simply referred to as “ObamaCare.”

ACA, which took full effect in 2014, is the largest expansion of the American welfare state since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. It has two major objectives: covering the uninsured and cost control. Let’s look at each in turn.

Covering the Uninsured On the coverage side, ACA was modelled closely on a similar plan that had been introduced in Massachusetts in 2006. To understand the logic of both the Massachusetts plan and ACA, consider the problem facing one major category of uninsured Americans: the many people who seek coverage in the individual insurance market but are turned down because they have pre-

One answer would be regulations requiring that insurance companies offer the same policies to everyone, regardless of medical history—

To make community rating work, it’s necessary to supplement it with other policies. Both the Massachusetts reform and ACA add two key features. First is the requirement that everyone purchase health insurance—

It’s important to realize that this system is like a three-

Will this act, once fully integrated, succeed in covering more or less everyone? The Massachusetts precedent is encouraging on that front: after four years, more than 98% of the state’s residents had health insurance and virtually all children were covered. Since the ACA is very similar in structure, it ought to produce similar results.

Cost Control But how does ACA control costs? In itself, the expansion of coverage raises U.S. health care spending, although not by as much as you might think. The uninsured are by and large relatively young, and the young have relatively low health care costs. (The elderly are already covered by Medicare.) The question is whether ACA can succeed in “bending the curve”: reducing the rate of growth of health costs over time.

ACA’s promise to control costs starts from the premise that the U.S. medical system had skewed incentives that wasted resources. Because most care in the United States is paid for by insurance, neither doctors nor patients have an incentive to worry about costs. In fact, because health care providers are generally paid for each procedure they perform, there’s a financial incentive to provide additional care—

The act attempts to correct these skewed incentives in a variety of ways, from stricter oversight of reimbursements, to linking payments to a procedure’s medical value, to paying health care providers for improved health outcomes rather than the number of procedures, and by limiting the tax deductibility of employment-

Is Canadian Health Care Spending Sustainable?

The Canadian health care system is a key part of Canada’s welfare state. A 2011 Nanos Research poll found that 94% of Canadians were in favour of preserving public health care. In fact, health care is often cited as the biggest issue for voters, beating out issues like taxes, job creation, retirement security, and the environment. But as Figure 18-7 clearly shows, Canadian health care spending as a percentage of total income has been rising. Canadians are right to be concerned about whether the public health care system is sustainable. Can the system survive? In what form? And what, if anything, can Canadians do to help keep the system running?

Between 1960 and 2011 health care costs rose about 350% in the United States and just over 200% in Canada. Canada’s public system experienced much smaller cost increases than the United States system with its dependence on for-profit health insurance and health care providers.

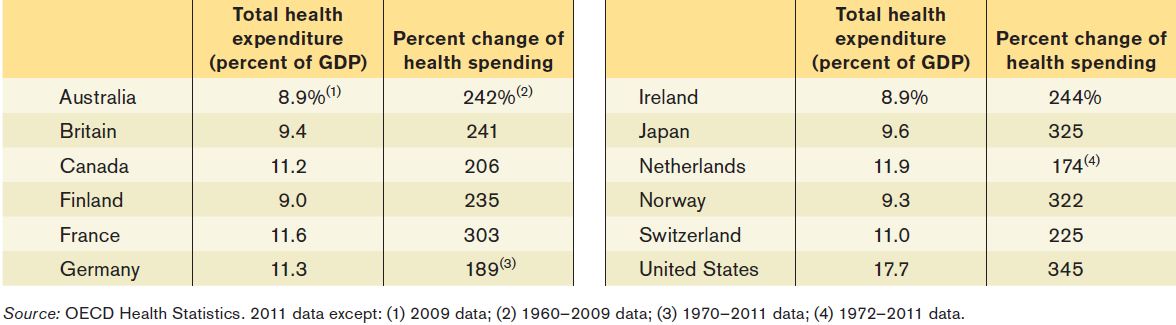

But you might ask if this is a fair comparison—what about other industrialized nations? As it turns out, health care costs are rising throughout the developed world. Table 18-7 shows total health care spending as a percentage of total income and the percentage growth of this amount between 1960 and 2011 for a number of major OECD countries. Canada’s total health care spending, at 11.2% of total income in 2011, is by no means on the low end for these countries. But at the same time it is not the highest either, nor has it grown any faster than health care costs in these other nations. According to the 2001 Romanov Commission report on the future of health care in Canada, publicly funded health care is both feasible and efficient. The much-publicized problems of Canada’s health care system stem from the fact that it is chronically underfunded.

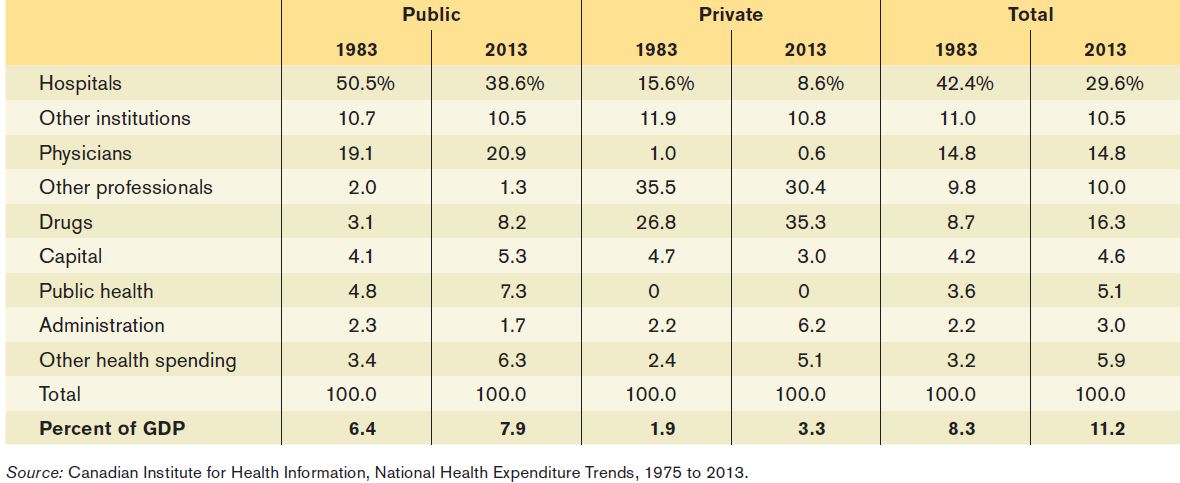

Table 18-8 attempts to address what exactly is driving health care costs up. This table compares Canadian health care spending in 1983 and 2013. It tabulates spending over major categories and shows the percentage of public, private, and total health care spending in each category. For example, in 1983, 19.1% of public health care spending went to physicians and rose slightly to 20.9% in 2013. In 1983, 1.0% of all private health care spending went to physicians and this share declined to 0.6% of all private health care spending. The table also presents the health care spending as a percentage of GDP, showing that health care costs rose from 8.3% of GDP in 1983 to 11.3% in 2013.

Interestingly, while health care costs now represent a larger share of GDP, the total share spent on hospitals has shrunk. The shares spent on doctors and other professionals have remained stable. What we see instead is that the greatest cost pressures are coming from prescription drugs (both publicly and private funded), public health, and rising administration costs in the private sector.

The reason spending on drugs rose so quickly lies in two related areas. Medical progress offers new drugs for previously untreatable conditions, though often at great expense. Also, the aging population drives up drug costs since older citizens are much more likely to need prescription drugs than younger, healthier patients. This is exactly why some have called on the federal government to take the lead in negotiating with brand name pharmaceutical companies for price concessions, either in return for longer patent protection or through the bulk buying of drugs at the national scale. If this can be achieved, the health care system costs should be more sustainable for the long run. But is this feasible and will it be enough? Sadly, there are no easy answers to these questions.

In 2014, the health care accord that set the funding and health care service delivery agreements between the federal, provincial, and territorial governments expired and was being renegotiated. Unfortunately, at the time of writing, the federal government was ignoring the calls of the provinces and territories to come together and work on a deal, and instead unilaterally announced tens of billions worth of cuts to health care that will come into effect after the next federal election. Supporters of public not-for-profit health care were left scrambling to fight against what they saw as the next big threat to Canadian health care and another push toward the end of a single-payer system with for-profit health care.

TOMMY DOUGLAS, THE GREATEST CANADIAN

Tommy Douglas is one the most prominent Canadians of the past century. In 1935, Douglas was elected to Parliament as a member of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), Canada’s first national social democratic party. In 1944, Douglas’ CCF won a huge majority in the Saskatchewan provincial election. So Douglas became not only the premier of Saskatchewan (a post he held for 17 years), but also leader of the first socialist government in North America. Douglas introduced many measures geared toward improving the welfare of society. Some of the most lasting measures were in the field of health care services.

Starting in 1944, free medical, hospital, and dental services were introduced for pensioners. Treatment of severe diseases such as cancer, tuberculosis, and STIs was made free for all.

In 1947, Douglas introduced a universal hospitalization insurance plan paid for by the provincial treasury and with a $5 levy per person. In 1959, Douglas announced plans to introduce Medicare: a universal, prepaid, publicly administered medical insurance plan to cover hospital and doctors services, including preventative care. His proposal was aided by Prime Minister Diefenbaker’s 1958 promise that the federal government would pay 50% of the cost of any provincial hospital plan. In 1961, after 17 years in the office, he resigned from his position as premier to become the leader of the federal New Democratic Party. The next year, Saskatchewan’s Medicare plan came into force on July 1, 1962. Within the next decade, all the provinces had adopted their own provincial plans similar in design to Saskatchewan’s Medicare and half paid for by the federal government.

For his contributions as the father of universal health care in Canada and for his other works, Tommy Douglas was voted the greatest Canadian of all time in a CBC survey in 2004.

Quick Review

Canada has a universal health care system that is available to all for free. The provincial, territorial, and federal governments operate a single-payer system, funding 100% of the costs of all covered medical services.

In the United States, health insurance satisfies an important need because expensive medical treatment is unaffordable for most families. Private health insurance has an inherent problem: the adverse selection death spiral. Screening by insurance companies reduces the problem, and employment-based health insurance, the way most Americans are covered, avoids it altogether.

The majority of Americans not covered by private insurance are covered by Medicare, which is a non-means-tested single-payer system for those over 65, and Medicaid, which is available based on income.

Compared to other wealthy countries, the United States depends more heavily on private health insurance, has higher health care spending per person, higher administrative costs, and higher drug prices, but without clear evidence of better health outcomes.

Health care costs everywhere are increasing rapidly due to scientific progress and an aging population.

Check Your Understanding 18-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 18-3

Question 18.7

Jiro is an international student enrolled in a four-year degree program. He is required to enroll in a health insurance program run by his school.

Explain how Jiro and his parents benefit from this health insurance program even though, given his age, it is unlikely that he will need expensive medical treatment.

Explain how his school’s health insurance program avoids the adverse selection death spiral.

The program benefits Jiro and his parents because the pool of all international students contains a representative mix of healthy and less healthy people, rather than a selected group of people who want insurance because they expect to pay high medical bills. In that respect, this insurance is like employment-based health insurance. Because no student can opt out, the school can offer health insurance based on the health care costs of its average student. If each student had to buy his or her own health insurance, some students would not be able to obtain any insurance and many would pay more than they do to the school’s insurance program.

Since all international students are required to enrol in its health insurance program, even the healthiest students cannot leave the program in an effort to obtain cheaper insurance tailored specifically to healthy people. If this were to happen, the school’s insurance program would be left with an adverse selection of less healthy students and so would have to raise premiums, beginning the adverse selection death spiral. But since no student can leave the insurance program, the school’s program can continue to base its premiums on the average student’s probability of requiring health care, avoiding the adverse selection death spiral.

Question 18.8

According to its critics, what accounts for the higher costs of the U.S. health care system compared to those of other wealthy countries?

According to critics, part of the reason the U.S. health care system is so much more expensive than those of other countries is its fragmented nature. Since each of the many insurance companies has significant administrative (overhead) costs—in part because each insurance company incurs marketing costs and exerts significant effort in weeding out high-risk insureds—the system tends to be more expensive than one in which there is only a single medical insurer. Another part of the explanation is that U.S. medical care includes many more expensive treatments than found in other wealthy countries, pays higher physician salaries, and has higher drug prices.