18.4 The Debate over the Welfare State

The goals of the welfare state seem laudable: to help the poor, to protect against severe economic hardship, and to ensure access to essential health care. But good intentions don’t always make for good policy. There is an intense debate about how large the welfare state should be, a debate that partly reflects differences in philosophy but also reflects concern about the possibly counterproductive effects on incentives of welfare state programs. Disputes about the size of the welfare state are also one of the defining issues of modern Canadian politics.

Problems with the Welfare State

There are two different arguments against the welfare state. One, which we described earlier in this chapter, is based on philosophical concerns about the proper role of government. As we learned, some political theorists believe that redistributing income is not a legitimate role of government. Rather, they believe that government’s role should be limited to maintaining the rule of law, providing public goods, and managing externalities.

The more conventional argument against the welfare state involves the trade-

But this must be balanced against the efficiency costs of high marginal tax rates. Consider an extremely progressive tax system that imposes a marginal rate of 90% on very high incomes. The problem is that such a high marginal rate reduces the incentive to increase a family’s income by working hard or making risky investments. As a result, an extremely progressive tax system tends to make society as a whole poorer, which could hurt even those the system was intended to benefit. That’s why even economists who strongly favour progressive taxation don’t support a return to the extremely progressive system that prevailed in 1948, when the top Canadian marginal income tax rate was 80%. So, the design of the tax system involves a trade-

A similar trade-

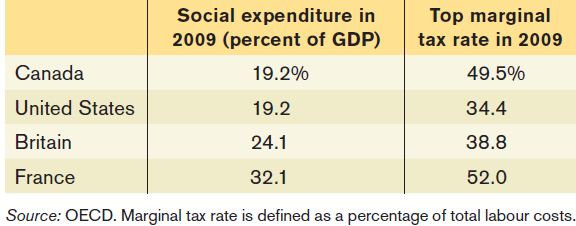

Table 18-9 shows “social expenditure,” a measure that roughly corresponds to total welfare state spending, as a percentage of GDP in Canada, the United States, Britain, and France. It also compares this with an estimate of the top marginal tax rate faced by an average single wage-

One way to hold down the costs of the welfare state is to means-

This feature of means-

OCCUPY WALL STREET

In the fall of 2011, Zuccotti Park, a small open space in Manhattan’s financial district, was taken over by protestors, part of a movement known as “Occupy Wall Street.” The protestors had a number of grievances, but the most pressing were their complaints about Wall Street and its perceived contribution to growing inequality. The Occupy Wall Street takeover and protests inspired similar protests in hundreds of cities in dozens of countries around the entire world, including every province in Canada. “We are the 99 percent!” became the movement’s favourite slogan, a reference to the large increase in share of income going to the top 1 percent of the population. Wall Street, they charged, contributed to growing inequality by paying its bankers huge salaries and bonuses, while engaging in overly risky behaviour that led to the U.S. housing boom and bust of 2007–2009 that decimated the global economy. Was this a reasonable charge?

Those who found it unreasonable pointed to the contributions that Wall Street, and the American finance industry in general, have made to the U.S. economy. Compared to other countries, the United States is a leader in financial services and innovation, generating billions annually in revenues, and attracting trillions of dollars of investment from abroad. High salaries on Wall Street, they contend, are simply the rewards to skill and hard work in the competitive market for talent on Wall Street.

What is incontrovertible, however, are the data that show that incomes in the finance industry have contributed to growing inequality in the United States. This is especially clear when you look not at the top percentile of the income distribution, but an even smaller group, the top 0.1 percent—

Although financial industry people are a minority (18%), within this income elite—

Even so, the combined effect of the major means-

The Politics of the Welfare State

In 1791, in the early phase of the French Revolution, French citizens convened a congress, the Legislative Assembly, in which representatives were seated according to social class: the upper classes, who pretty much liked the way things were, sat on the right; commoners, who wanted big changes, sat on the left. Ever since, political commentators refer to politicians as being on the “right” (more conservative) or on the “left” (more liberal).

But what do modern politicians on the left and right disagree about? In Canada, besides concerns over the environment and globalization, they mainly disagree about the appropriate size of the welfare state. The debate over the need for a national child care program is a case in point, with support split almost entirely according to party lines—Liberals and NDP (on the left) in favour of a national program and Conservatives (on the right) opposed.

You might think that saying that political debate is really about just one thing—how big to make the welfare state—is a huge oversimplification. But anyone can see that most MPs and MPPs vote along party lines. Politicians on the left tend to favour a larger welfare state and those on the right to oppose it. This left–right distinction is central to today’s politics. In recent decades, it has become much clearer where the members of the major federal political parties stand on the left–right spectrum.

Can economic analysis help resolve this political conflict? Only up to a point.

Some of the political controversy over the welfare state involves differences in opinion about the trade-offs we have just discussed: if you believe that the disincentive effects of generous benefits and high taxes are very large, you’re likely to look less favourably on welfare state programs than if you believe they’re fairly small. Economic analysis, by improving our knowledge of the facts, can help resolve some of these differences.

To an important extent, however, differences of opinion on the welfare state reflect differences in values and philosophy. And those are differences economics can’t resolve.

FRENCH FAMILY VALUES

France has one of the largest welfare states of any major advanced economy. As we’ve already described, France has much higher social spending than found in North America as a percentage of total national income, and French citizens face much higher tax rates than North Americans. One argument against a large welfare state is that it has negative effects on efficiency. Does French experience support this argument?

On the face of it, the answer would seem to be a clear yes. French GDP per capita—the total value of the economy’s output, divided by the total population—is only about 80% of the Canadian and U.S. levels. This reflects the fact that the French work less: French workers and North American workers have almost exactly the same productivity per hour, but a smaller fraction of the French population is employed, and the average French employee works substantially fewer hours over the course of a year than his or her North American counterpart. Some economists have argued that high tax rates in France explain this difference: the incentives to work are weaker in France than in North America because the government takes away so much of what you earn from an additional hour of work.

A closer examination, however, reveals that the story is more complicated than that. The low level of employment in France is entirely the result of low rates of employment among the young and the old; 80% of French residents of prime working age, 25–54, are employed, exactly the same percentage as in Canada and the United States. So high tax rates don’t seem to discourage the French from working in the prime of their lives. But only about 30% of 15- to 24-year-olds are employed in France, compared with more than half of 15- to 24-year-olds in Canada and the United States. And young people in France don’t work in part because they don’t have to: college education is generally free, and students receive financial support, so French students rarely work while attending school. The French will tell you that that’s a virtue of their system, not a problem.

Shorter working hours also reflect factors besides tax rates. French law requires employers to offer at least a month of paid vacation, but Canadian workers are guaranteed only 10 paid days off. Most U.S. workers get less than two weeks off and have no guaranteed number of paid vacation days. Here, too, the French will tell you that their policy is better than ours because it helps families spend time together.

The aspect of French policy even the French agree is a big problem is that their retirement system allows workers to collect generous pensions even if they retire very early. As a result, only 40% of French residents between the ages of 55 and 64 are employed, compared with more than 60% of North Americans. The cost of supporting all those early retirees is a major burden on the French welfare state—and getting worse as the French population ages.

Quick Review

Intense debate on the size of the welfare state centres on philosophy and on equity-versus-efficiency concerns. The high marginal tax rates needed to finance an extensive welfare state can reduce the incentive to work. Holding down the cost of the welfare state by means-testing can also cause inefficiency through notches that create high effective marginal tax rates for benefit recipients.

Politics is often depicted as an opposition between left and right; in modern-day Canada, that division mainly involves disagreement over the appropriate size of the welfare state.

Check Your Understanding 18-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 18-4

Question 18.9

Explain how each of the following policies creates a disincentive to work or undertake a risky investment.

A high sales tax on consumer items

The complete loss of a housing subsidy when yearly income rises above $25 000

Recall one of the principles from Chapter 1: one person’s spending is another person’s income. A high sales tax on consumer items is the same as a high marginal tax rate on income. As a result, the incentive to earn income by working or by investing in risky projects is reduced, since the payoff, after taxes, is lower.

If you lose a housing subsidy as soon as your income rises above $25 000, your incentive to earn more than $25 000 is reduced. If you earn exactly $25 000, you obtain the housing subsidy; however, as soon as you earn $25 001, you lose the entire subsidy, making you worse off than if you had not earned the additional dollar. The complete withdrawal of the housing subsidy as income rises above $25 000 is what economists refer to as a notch.

Question 18.10

Over the past 40 years, has the polarization in the Canadian Parliament increased, decreased, or stayed the same?

Over the past 40 years, polarization in Canadian politics has increased. Forty years ago, some Conservatives were to the left of some Liberals. Today, the rightmost Liberal and NDP politicians appear to be to the left of the leftmost Conservatives.

Welfare State Entrepreneurs

“Wiggo Dalmo is a classic entrepreneurial type: the Working Class Kid Made Good.” So began a profile in the January 2011 issue of Inc. magazine. Dalmo began as an industrial mechanic who worked for a large company, repairing mining equipment. Eventually, however, he decided to strike out on his own and start his own business. Momek, the company he founded, eventually grew into a $44 million, 150-employee operation that does a variety of contract work on oil rigs and in mines.

You can read stories like this all the time in business magazines. What was unusual about this particular article is that Dalmo and his company are Norwegian—and Norway, like other Scandinavian countries, has a very generous welfare state, supported by high levels of taxation. So what does Dalmo think of that system? He approves, saying that Norway’s tax system is “good and fair,” and he thinks the system is good for business. In fact, the Inc. article was titled, “In Norway, Start-Ups Say Ja to Socialism.”

Why? After all, the financial rewards for being a successful entrepreneur are more limited in a country like Norway, with its high taxes. But there are other considerations. For example, a Canadian thinking of leaving a large company to start a new business needs to worry about whether he or she will be able to get supplementary health insurance, whereas a Norwegian in the same position is assured of health care regardless of employment. And the downside of failure is larger in North America, where minimal aid is offered to the unemployed.

Still, is Wiggo Dalmo an exceptional case? Table 18-10 shows the nations with the highest level of entrepreneurial activity, according to a study financed by the U.S. Small Business Administration, which tried to quantify the level of entrepreneurial activity in different nations. Canada and the United States made it into the top 10, but so did Norway. And the list also includes Denmark, New Zealand, Sweden, and Australia—all nations with high taxes and extensive social insurance programs.

The moral is that when comparing how business friendly different welfare state systems really are, you have to think a bit past the obvious question of the level of taxes.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 18.11

Why does Norway have to have higher taxes overall than Canada?

Question 18.12

This case suggests that government-paid health care helps entrepreneurs. How does this relate to the arguments we made for social insurance in the text?

Question 18.13

How would the incentives of people like Wiggo Dalmo be affected if Norwegian health care was means-tested instead of available to all?

Question 18.14

Briefly explain how this case influences the care one should use when making international comparisons of competitiveness based on a single indicator such as labour costs (hourly wages) or (highest marginal) personal income tax rates.