1.1 Principles That Underlie Individual Choice: The Core of Economics

Individual choice is the decision by an individual of what to do, which necessarily involves a decision of what not to do.

Every economic issue involves, at its most basic level, individual choice—decisions by an individual about what to do and what not to do. In fact, you might say that it isn’t economics if it isn’t about choice.

Step into a big store like Walmart or Hudson’s Bay. There are thousands of different products available, and it is extremely unlikely that you—

The fact that those products are on the shelf in the first place involves choice—

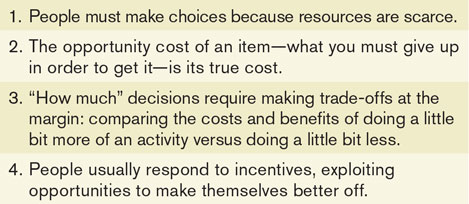

Four economic principles underlie the economics of individual choice, as shown in Table 1-1. We’ll now examine each of these principles in more detail.

Principle #1: Choices Are Necessary Because Resources Are Scarce

You can’t always get what you want. Everyone would like to have a beautiful house in a great location (and have help with the housecleaning), a new car or two, and a nice vacation in a fancy hotel. But even in a rich country like Canada, not many families can afford all that. So they must make choices—

Limited income isn’t the only thing that keeps people from having everything they want. Time is also in limited supply: there are only 24 hours in a day. And because the time we have is limited, choosing to spend time on one activity also means choosing not to spend time on a different activity—

This leads us to our first principle of individual choice:

People must make choices because resources are scarce.

A resource is anything that can be used to produce something else.

A resource is anything that can be used to produce something else. Lists of the economy’s resources usually begin with land, labour (the time of workers), capital (machinery, buildings, and other manufactured productive assets), and human capital (the educational achievements and skills of workers). A resource is scarce when there’s not enough of the resource available to satisfy all the ways a society wants to use it. There are many scarce resources. These include natural resources—

Resources are scarce—not enough of the resources are available to satisfy all the various ways a society wants to use them.

Just as individuals must make choices, the scarcity of resources means that society as a whole must make choices. One way a society makes choices is by allowing them to emerge as the result of many individual choices, which is what usually happens in a market economy. For example, Canadians as a group have only so many hours in a week: how many of those hours will they spend going to supermarkets to get lower prices, rather than saving time by shopping at convenience stores? The answer is the sum of individual decisions: each of the millions of individuals in the economy makes his or her own choice about where to shop, and the overall choice is simply the sum of those individual decisions.

But for various reasons, there are some decisions that a society decides are best not left to individual choice. For example, the authors live in areas that until recently were mainly farmland but are now being rapidly built up. Most local residents feel that the community would be a more pleasant place to live if some of the land was left undeveloped. But no individual has an incentive to keep his or her land as open space, rather than sell it to a developer. So, a trend has emerged in many communities across Canada of governments either purchasing undeveloped land, or putting restrictions on its use, to preserve it as open space. For example, the federal government created Rouge Park, Canada’s first urban national park, in the Greater Toronto area, to protect about 40 square kilometres of wilderness. The Agricultural Land Reserve was created by the provincial government of British Columbia to protect about 47 000 square kilometres of agricultural land. The Ontario government established the 7300 square kilometre greenbelt surrounding the Golden Horseshoe region to protect farmland and natural space from urban development. Similar greenbelts are proposed for Montreal and Quebec City.

We’ll see in later chapters why decisions about how to use scarce resources are often best left to individuals but sometimes should be made at a higher, community-

Principle #2: The True Cost of Something Is Its Opportunity Cost

It is the last term before you graduate, and your class schedule allows you to take only one elective. There are two, however, that you would really like to take: Intro to Computer Graphics and History of Jazz.

The real cost of an item is its opportunity cost: what you must give up in order to get it.

Suppose you decide to take the History of Jazz course. What’s the cost of that decision? It is the fact that you can’t take the computer graphics class, your next best alternative choice. Economists call that kind of cost—

The opportunity cost of an item—

So the opportunity cost of taking the History of Jazz class is the benefit you would have derived from the Intro to Computer Graphics class.

The concept of opportunity cost is crucial to understanding individual choice because, in the end, all decisions dealing with scarcity involve opportunity costs. That’s because every choice you make means forgoing some other alternative and these costs can be both monetary and non-

Let’s consider two cases for our elective course example. First, suppose that taking any elective class involves a tuition fee of $750. In this case, you would have to spend that $750 no matter which class you take. So what you give up to take the History of Jazz class is still only the benefit derived from the computer graphics class, period—

So the opportunity costs of taking the History of Jazz class are both monetary (any additional tuition you paid over the computer graphics class) and non-

Sometimes the money you have to pay for something is a good indication of its opportunity cost. But many times it is not. One very important example of how poorly monetary cost alone can indicate opportunity cost is the cost of attending college or university. Tuition and housing are major monetary expenses for most post-

It’s easy to see that the opportunity cost of going to a post-

Principle #3: “How Much” Is a Decision at the Margin

Some important decisions involve an “either–

Suppose you are taking both economics and chemistry. And suppose you are a premed student, so your grade in chemistry matters more to you than your grade in economics. Does that therefore imply that you should spend all your study time on chemistry and wing it on the economics exam? Probably not; even if you think your chemistry grade is more important, you should put some effort into studying economics.

You make a trade-off when you compare the costs with the benefits of doing something.

Spending more time studying chemistry involves a benefit (a higher expected grade in that course) and a cost (you could have spent that time doing something else, such as studying to get a higher grade in economics). That is, your decision involves a trade-off—a comparison of costs and benefits.

How do you decide this kind of “how much” question? The typical answer is that you make the decision a bit at a time, by asking how you should spend the next hour. Say both exams are on the same day, and the night before you spend time reviewing your notes for both courses. At 6:00 P.M., you decide that it’s a good idea to spend at least an hour on each course. At 8:00 P.M., you decide you’d better spend another hour on each course. At 10:00 P.M., you are getting tired and figure you have one more hour to study before bed—

Note how you’ve made the decision to allocate your time: at each point the question is whether or not to spend one more hour on either course. And in deciding whether to spend another hour studying for chemistry, you weigh the costs (an hour forgone of studying for economics or an hour forgone of sleeping) versus the benefits (a likely increase in your chemistry grade). As long as the benefit of studying chemistry for one more hour outweighs the cost, you should choose to study for that additional hour.

Decisions of this type—

Decisions about whether to do a bit more or a bit less of an activity are marginal decisions. The study of such decisions is known as marginal analysis.

“How much” decisions require making trade-

The study of such decisions is known as marginal analysis. Many of the questions that we face in economics—

Principle #4: People Usually Respond to Incentives, Exploiting Opportunities to Make Themselves Better Off

One day, while listening to the morning financial news, one of the American-based authors of this textbook heard a great tip about how to park cheaply in Manhattan. Garages in the Wall Street area charge as much as $30 per day. But according to the newscaster, some people had found a better way: instead of parking in a garage, they had their oil changed at the Manhattan Jiffy Lube, where it costs $19.95 to change your oil—and they keep your car all day!

It’s a great story, but unfortunately it turned out not to be true—in fact, there is no Jiffy Lube in Manhattan. But if there were, you can be sure there would be a lot of oil changes there. Why? Because when people are offered opportunities to make themselves better off, they normally take them—and if they could find a way to park their car all day for $19.95 rather than $30, they would.

In this example economists say that people are responding to an incentive—an opportunity to make themselves better off. We can now state our fourth principle of individual choice:

People usually respond to incentives, exploiting opportunities to make themselves better off.

An incentive is anything that offers rewards to people who change their behaviour.

When you try to predict how individuals will behave in an economic situation, it is a very good bet that they will respond to incentives—that is, exploit opportunities to make themselves better off. Furthermore, individuals will continue to exploit these opportunities until they have been fully exhausted. If there really were a Manhattan Jiffy Lube and an oil change really were a cheap way to park your car, we can safely predict that before long the waiting list for oil changes would be weeks, if not months, long.

In fact, the principle that people will exploit opportunities to make themselves better off is the basis of all predictions by economists about individual behaviour. If the earnings of those who get MBAs soar while the earnings of those who get law degrees decline, we can expect more students to go to business school and fewer to go to law school. If the price of gasoline rises and stays high for an extended period of time, we can expect people to buy smaller cars with better fuel efficiency—making themselves better off in the presence of higher gas prices by driving more fuel-efficient cars.

One last point: economists tend to be skeptical of any attempt to change people’s behaviour that doesn’t change their incentives. For example, a plan that calls on manufacturers to reduce pollution voluntarily probably won’t be effective because it hasn’t changed manufacturers’ incentives. In contrast, a plan that gives them a financial reward to reduce pollution or a penalty for not doing so is a lot more likely to work because it has changed their incentives.

CASHING IN AT SCHOOL

The true reward for learning is, of course, the learning itself. Many students, however, struggle with their motivation to study and work hard. Teachers and policy-makers have been particularly challenged to help students from disadvantaged backgrounds, who often have poor school attendance, high dropout rates, and low standardized test scores. In a 2007–2008 study, Harvard economist Roland Fryer Jr. found that monetary incentives—cash rewards—could improve students’ academic performance in schools in economically disadvantaged areas. How cash incentives work, however, is both surprising and predictable.

Fryer conducted his research in four different school districts, employing a different set of incentives and a different measure of performance in each. In New York City, students were paid according to their scores on standardized tests; in Chicago, they were paid according to their grades; in Washington, D.C., they were paid according to attendance and good behaviour as well as their grades; in Dallas, Grade Two students were paid each time they read a book. Fryer evaluated the results by comparing the performance of students who were in the program to other students in the same school who were not.

In New York, the program had no perceptible effect on test scores. In Chicago, students in the program got better grades and attended class more. In Washington, the program boosted the outcomes of the kids who are normally the hardest to reach, those with serious behavioural problems, raising their test scores by an amount equivalent to attending five extra months of school. The most dramatic results occurred in Dallas, where students significantly boosted their reading-comprehension test scores; results continued into the next year, after the cash rewards had ended.

So what explains the various results?

To motivate students with cash rewards, Fryer found that students had to believe that they could have a significant effect on the performance measure. So in Chicago, Washington, and Dallas—where students had a significant amount of control over outcomes such as grades, attendance, behaviour, and the number of books read—the program produced significant results. But because New York students had little idea how to affect their score on a standardized test, the prospect of a reward had little influence on their behaviour. Also, the timing of the reward matters: a $1 reward has more effect on behaviour if performance is measured at shorter intervals and the reward is delivered soon after.

Fryer’s experiment revealed some critical insights about how to motivate behaviour with incentives. How incentives are designed is very important: the relationship between effort and outcome, as well as the speed of reward, matters a lot. Moreover, the design of incentives may depend quite a lot on the characteristics of the people you are trying to motivate: what motivates a student from an economically privileged background may not motivate a student from an economically disadvantaged one. Fryer’s insights give teachers and policy-makers an important new tool for helping disadvantaged students succeed in school.

In Canada, using publicly funded cash incentives to motivate at-risk students is a controversial topic. Some educators claim that financial incentives do work, and are needed, citing the success of such a program in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba. Aboriginal students at Portage Collegiate Institute receive $50 per month to attend school regularly and complete their homework. Students who graduate from Grade 12 receive $1000. This program is funded by the Long Plains First Nations. The result? More students are attending and graduating from Portage Collegiate. Similar programs are operating elsewhere in Canada. But many people think that other solutions should be found to encourage students. When, in 2010, the Toronto District School Board suggested paying students from disadvantaged communities, provincial politicians firmly rejected the plan.

So are we ready to do economics? Not yet—because most of the interesting things that happen in the economy are the result not merely of individual choices but of the way in which individual choices interact.

BOY OR GIRL? IT DEPENDS ON THE COST

One fact about China is indisputable: it’s a big country with lots of people. As of 2013, the population of China was about 1 349 586 000. That’s right: over one billion three hundred million.

In 1978, the government of China introduced the “one-child policy” to address the economic and demographic challenges presented by China’s large population. China was very, very poor in 1978, and its leaders worried that the country could not afford to adequately educate and care for its growing population. The average Chinese woman in the 1970s was giving birth to more than five children during her lifetime. So the government restricted most couples, particularly those in urban areas, to one child, imposing penalties on those who defied the mandate. As a result, by 2013 the average number of births for a woman in China was only 1.6.

But the one-child policy had an unfortunate unintended consequence. Because China is an overwhelmingly rural country and sons can perform the manual labour of farming, families had a strong preference for sons over daughters. In addition, tradition dictates that brides become part of their husbands’ families and that sons take care of their elderly parents. As a result of the one-child policy, China soon had too many “unwanted girls.” Some were given up for adoption abroad, but all too many simply “disappeared” during the first year of life, the victims of neglect and mistreatment.

India, another highly rural poor country with high demographic pressures, also has a significant problem with “disappearing girls.” In 1990, Amartya Sen, an Indian-born British economist who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in 1998, estimated that there were up to 100 million “missing women” in Asia. (The exact figure is in dispute, but it is clear that Sen identified a real and pervasive problem.)

Demographers have recently noted a distinct turn of events in China, which is quickly urbanizing. In all but one of the provinces with urban centres, the gender imbalance between boys and girls peaked in 1995 and has steadily fallen toward the biologically natural ratio since then. Many believe that the source of the change is China’s strong economic growth and increasing urbanization. As people move to cities to take advantage of job growth there, they don’t need sons to work the fields. Moreover, land prices in Chinese cities are skyrocketing, making the custom of parents buying an apartment for a son before he can marry unaffordable for many. To be sure, sons are still preferred in the rural areas. But as a sure mark of how times have changed, Internet websites have recently popped up that advise couples on how to have a girl rather than a boy.

Quick Review

All economic activities involve individual choice.

People must make choices because resources are scarce.

The real cost of something is its opportunity cost—what you must give up to get it. All costs are opportunity costs. Monetary costs are sometimes a good indicator of opportunity costs, but not always.

Many choices involve not whether to do something but how much of it to do. “How much” choices call for making a trade-off at the margin. The study of marginal decisions is known as marginal analysis.

Because people usually exploit opportunities to make themselves better off, incentives can change people’s behaviour.

Check Your Understanding 1-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1-1

Question 1.1

Explain how each of the following situations illustrates one of the four principles of individual choice.

You are on your third trip to a restaurant’s all-you-can-eat dessert buffet and are feeling very full. Although it would cost you no additional money, you forgo a slice of coconut cream pie but have a slice of chocolate cake.

Even if there were more resources in the world, there would still be scarcity.

Different teaching assistants teach several Economics 101 tutorials. Those taught by the teaching assistants with the best reputations fill up quickly, with spaces left unfilled in the ones taught by assistants with poor reputations.

To decide how many hours per week to exercise, you compare the health benefits of one more hour of exercise to the effect on your grades of one fewer hour spent studying.

This illustrates the concept of opportunity cost. Given that a person can only eat so much at one sitting, having a slice of chocolate cake requires that you forgo eating something else, such as a slice of coconut cream pie.

This illustrates the concept that resources are scarce. Even if there were more resources in the world, the total amount of those resources would be limited. As a result, scarcity would still arise. For there to be no scarcity, there would have to be unlimited amounts of everything (including unlimited time in a human life), which is clearly impossible.

This illustrates the concept that people usually exploit opportunities to make themselves better off. Students will seek to make themselves better off by signing up for the tutorials of teaching assistants with good reputations and avoiding those teaching assistants with poor reputations. It also illustrates the concept that resources are scarce. If there were unlimited spaces in tutorials with good teaching assistants, they would not fill up.

This illustrates the concept of marginal analysis. Your decision about allocating your time is a “how much” decision: how much time spent exercising versus how much time spent studying. You make your decision by comparing the benefit of an additional hour of exercising to its cost, the effect on your grades of one fewer hour spent studying.

Question 1.2

You make $45 000 per year at your current job with Whiz Kids Consultants. You are considering a job offer from Brainiacs, Inc., that will pay you $50 000 per year. Which of the following are elements of the opportunity cost of accepting the new job at Brainiacs, Inc.?

The increased time spent commuting to your new job

The $45 000 salary from your old job

The more spacious office at your new job

Yes. The increased time spent commuting is a cost you will incur if you accept the new job. That additional time spent commuting—or equivalently, the benefit you would get from spending that time doing something else—is an opportunity cost of the new job.

Yes. One of the benefits of the new job is that you will be making $50 000. But if you take the new job, you will have to give up your current job; that is, you have to give up your current salary of $45 000. So $45 000 is one of the opportunity costs of taking the new job.

No. A more spacious office is an additional benefit of your new job and does not involve forgoing something else. So it is not an opportunity cost.