3.5 Changes in Supply and Demand

The 2010 floods in Pakistan came as a surprise, but the subsequent increase in the price of cotton was no surprise at all. Suddenly there was a decrease in supply: the quantity of cotton available at any given price fell. Predictably, a decrease in supply raises the equilibrium price.

The flooding in Pakistan is an example of an event that shifted the supply curve for a good without having much effect on the demand curve. There are many such events. There are also events that shift the demand curve without shifting the supply curve. For example, a medical report that chocolate is good for you increases the demand for chocolate but does not affect the supply. Events often shift either the supply curve or the demand curve, but not both; it is therefore useful to ask what happens in each case.

We have seen that when a curve shifts, the equilibrium price and quantity change. We will now concentrate on exactly how the shift of a curve alters the equilibrium price and quantity.

What Happens When the Demand Curve Shifts

Cotton and polyester are substitutes: if the price of polyester rises, the demand for cotton will increase, and if the price of polyester falls, the demand for cotton will decrease. But how does the price of polyester affect the market equilibrium for cotton?

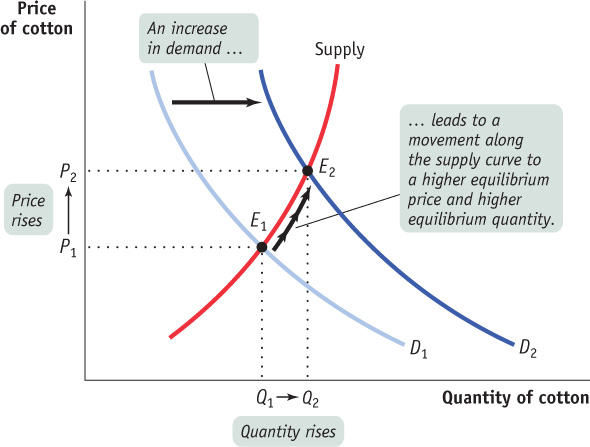

Figure 3-14 shows the effect of a rise in the price of polyester on the market for cotton. The rise in the price of polyester increases the demand for cotton. Point E1 shows the equilibrium corresponding to the original demand curve, with P1 the equilibrium price and Q1 the equilibrium quantity bought and sold.

An increase in demand is indicated by a rightward shift of the demand curve from D1 to D2. At the original market price P1, this market is no longer in equilibrium: a shortage occurs because the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. So the price of cotton rises and generates an increase in the quantity supplied, an upward movement along the supply curve. A new equilibrium is established at point E2, with a higher equilibrium price, P2, and higher equilibrium quantity, Q2. This sequence of events reflects a general principle: When demand for a good or service increases, the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity of the good or service both rise.

What would happen in the reverse case, a fall in the price of polyester? A fall in the price of polyester reduces the demand for cotton, shifting the demand curve to the left. At the original price, a surplus occurs as quantity supplied exceeds quantity demanded. The price falls and leads to a decrease in the quantity supplied, resulting in a lower equilibrium price and a lower equilibrium quantity. This illustrates another general principle: When demand for a good or service decreases, the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity of the good or service both fall.

To summarize how a market responds to a change in demand: An increase in demand leads to a rise in both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity. A decrease in demand leads to a fall in both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity.

What Happens When the Supply Curve Shifts

In the real world, it is a bit easier to predict changes in supply than changes in demand. Physical factors that affect supply, like weather or the availability of inputs, are easier to get a handle on than the fickle tastes that affect demand. Still, with supply as with demand, what we can best predict are the effects of shifts of the supply curve.

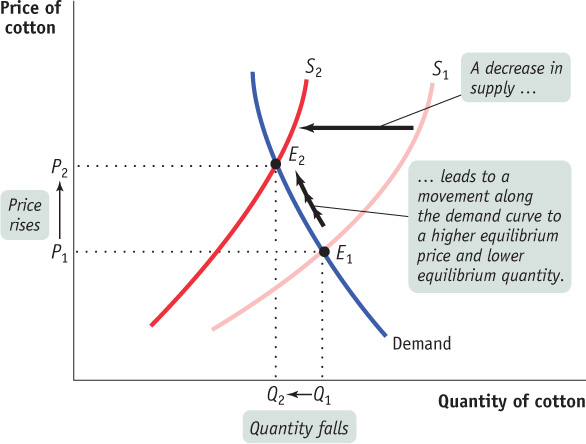

As we mentioned in this chapter’s opening story, devastating floods in Pakistan sharply reduced the supply of cotton in 2010. Figure 3-15 shows how this shift affected the market equilibrium. The original equilibrium is at E1, the point of intersection of the original supply curve, S1, and the demand curve, with an equilibrium price P1 and equilibrium quantity Q1. As a result of the bad weather, supply falls and S1 shifts leftward to S2. At the original price P1, a shortage of cotton now exists and the market is no longer in equilibrium. The shortage causes a rise in price and a fall in quantity demanded, an upward movement along the demand curve. The new equilibrium is at E2, with an equilibrium price P2 and an equilibrium quantity Q2. In the new equilibrium, E2, the price is higher and the equilibrium quantity lower than before. This can be stated as a general principle: When supply of a good or service decreases, the equilibrium price of the good or service rises and the equilibrium quantity of the good or service falls.

What happens to the market when supply increases? An increase in supply leads to a rightward shift of the supply curve. At the original price, a surplus now exists; as a result, the equilibrium price falls and the quantity demanded rises. This describes what happened to the market for cotton as the use of new technology increased cotton yields. We can formulate a general principle: When supply of a good or service increases, the equilibrium price of the good or service falls and the equilibrium quantity of the good or service rises.

To summarize how a market responds to a change in supply: An increase in supply leads to a fall in the equilibrium price and a rise in the equilibrium quantity. A decrease in supply leads to a rise in the equilibrium price and a fall in the equilibrium quantity.

WHICH CURVE IS IT, ANYWAY?

When the price of some good or service changes, in general, we can say that this reflects a change in either supply or demand. But it is easy to get confused about which one. A helpful clue is the direction of change in the quantity. If the quantity sold changes in the same direction as the price—

Simultaneous Shifts of Supply and Demand Curves

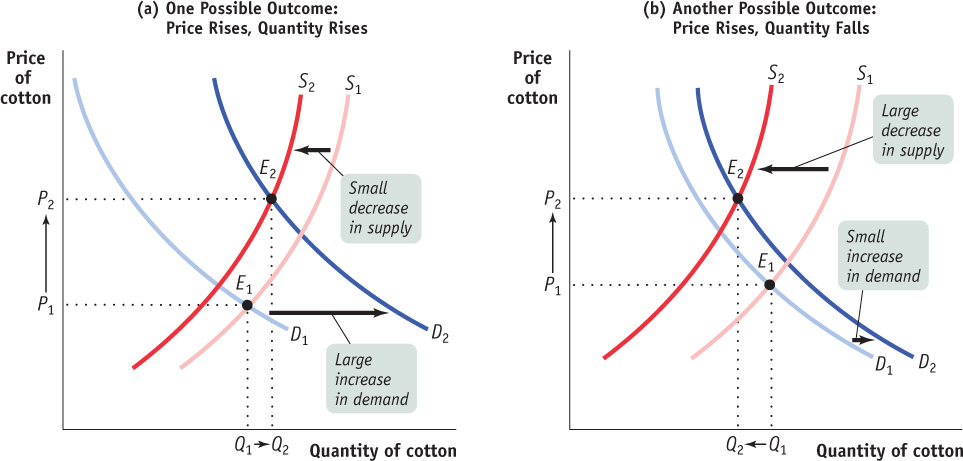

Finally, it sometimes happens that events shift both the demand and supply curves at the same time. This is not unusual; in real life, supply curves and demand curves for many goods and services shift quite often because the economic environment continually changes. Figure 3-16 illustrates two examples of simultaneous shifts. In both panels there is an increase in demand—that is, a rightward shift of the demand curve, from D1 to D2—say, for example, representing an increase in the demand for cotton due to changing tastes. Notice that the rightward shift in panel (a) is larger than the one in panel (b): we can suppose that panel (a) represents a year in which many more people than usual choose to buy jeans and cotton T-shirts and panel (b) represents a normal year. Both panels also show a decrease in supply—that is, a leftward shift of the supply curve from S1 to S2. Also notice that the leftward shift in panel (b) is relatively larger than the one in panel (a): we can suppose that panel (b) represents the effect of particularly bad weather in Pakistan and panel (a) represents the effect of a much less severe weather event.

TRIBULATIONS ON THE RUNWAY

You probably don’t spend much time worrying about the trials and tribulations of fashion models. Most of them don’t lead glamorous lives; in fact, except for a lucky few, life as a fashion model today can be very trying and not very lucrative. And it’s all because of supply and demand.

Consider the case of Bianca Gomez, a willowy 18-year-old from Los Angeles, with green eyes, honey-coloured hair, and flawless skin, whose experience was detailed in a Wall Street Journal article. Bianca began modelling while still in high school, earning about $30000 in modelling fees during her senior year. Having attracted the interest of some top designers in New York, she moved there after graduation, hoping to land jobs in leading fashion houses and photo-shoots for leading fashion magazines.

But once in New York, Bianca entered the global market for fashion models. And it wasn’t very pretty. Due to the ease of transmitting photos over the Internet and the relatively low cost of international travel, top fashion centres such as New York and Milan are now deluged with beautiful young women from all over the world, eagerly trying to make it as models. Although Russians, other Eastern Europeans, and Brazilians are particularly numerous, some hail from places such as Kazakhstan and Mozambique. As one designer said, “There are so many models now …. There are just thousands every year.”

Returning to our (less glamorous) economic model of supply and demand, the influx of aspiring fashion models from around the world can be represented by a rightward shift of the supply curve in the market for fashion models, which would by itself tend to lower the price paid to models. And that wasn’t the only change in the market. Unfortunately for Bianca and others like her, the tastes of many of those who hire models have changed as well. Over the past few years, fashion magazines have come to prefer using celebrities such as Angelina Jolie on their pages rather than anonymous models, believing that their readers connect better with a familiar face. This amounts to a leftward shift of the demand curve for models—again reducing the equilibrium price paid to them.

This was borne out in Bianca’s experiences. After paying her rent, her transportation, all her modelling expenses, and 20% of her earnings to her modelling agency (which markets her to prospective clients and books her jobs), Bianca found that she was barely breaking even. Sometimes she even had to dip into savings from her high school years. To save money, she ate macaroni and hot dogs; she travelled to auditions, often four or five in one day, by subway. As the Wall Street Journal reported, Bianca was seriously considering quitting modelling altogether.

In both cases, the equilibrium price rises from P1 to P2, as the equilibrium moves from E1 to E2. But what happens to the equilibrium quantity, the quantity of cotton bought and sold? In panel (a) the increase in demand is large relative to the decrease in supply, and the equilibrium quantity rises as a result. In panel (b), the decrease in supply is large relative to the increase in demand, and the equilibrium quantity falls as a result. That is, when demand increases and supply decreases, the actual quantity bought and sold in equilibrium can rise, fall, or remain the same, depending on how much the demand and supply curves have shifted.

In general, when supply and demand shift in opposite directions, we can’t predict what the ultimate effect will be on the quantity bought and sold. What we can say is that a curve that shifts a disproportionately greater distance than the other curve will have a disproportionately greater effect on the equilibrium quantity bought and sold. That said, we can make the following prediction about the outcome when the supply and demand curves shift in opposite directions:

When demand increases and supply decreases, the equilibrium price rises but the change in the equilibrium quantity is ambiguous.

When demand decreases and supply increases, the equilibrium price falls but the change in the equilibrium quantity is ambiguous.

But suppose that the demand and supply curves shift in the same direction. Before 2010, this was the case in the global market for cotton, where both supply and demand had increased over the past decade. Can we safely make any predictions about the changes in price and quantity? In this situation, the change in quantity bought and sold can be predicted, but the change in price is ambiguous. The two possible outcomes when the supply and demand curves shift in the same direction (which you should check for yourself) are as follows:

When both demand and supply increase, the equilibrium quantity rises but the change in equilibrium price is ambiguous.

When both demand and supply decrease, the equilibrium quantity falls but the change in equilibrium price is ambiguous.

THE RICE RUN OF 2008

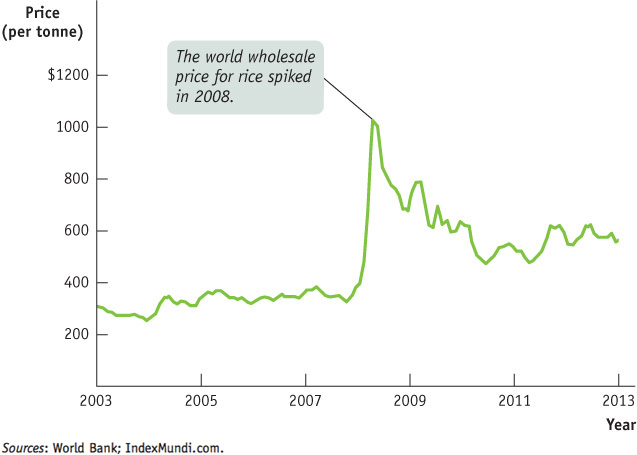

In April 2008, the price of rice exported from Thailand—a global benchmark for the price of rice traded in international markets—reached $1029 per tonne, up from $398 per tonne at the beginning of 2008. Within hours, prices for rice at major rice-trading exchanges around the world were breaking record levels. The factors that lay behind the surge in rice prices were both demand-related and supply-related: growing incomes in China and India, traditionally large consumers of rice; drought in Australia; and pest infestation in Vietnam. But it was also hoarding by farmers, panic buying by consumers, and an export ban by India, one of the largest exporters of rice, that explained the breathtaking speed of the rise in price.

In much of Asia, governments are major buyers of rice. They buy rice from their rice farmers, who are paid a government-set price, and then sell it to the poor at subsidized prices (prices lower than the market equilibrium price). In the past, the government-set price was better than anything farmers could get in the private market.

Now, even farmers in rural areas of Asia have access to the Internet and can see the price quotes on global rice exchanges. And as rice prices rose in response to changes in demand and supply, farmers grew dissatisfied with the government price and instead hoarded their rice in the belief that they would eventually get higher prices. This was a self-fulfilling belief, as the hoarding shifted the supply curve leftward and raised the price of rice even further.

At the same time, India, one of the largest growers of rice, banned Indian exports of rice in order to protect its domestic consumers, causing yet another leftward shift of the supply curve and pushing the price of rice even higher.

As shown in Figure 3-17, the effects even spilled over to North America, which had not suffered any fall in its rice production. North American rice consumers grew alarmed when large retailers limited some bulk rice purchases by consumers in response to the turmoil in the global rice market.

Fearful of paying even higher prices in the future, panic buying set in. As one woman who was in the process of buying 30 pounds of rice said, “We don’t even eat that much rice. But I read about it in the newspaper and decided to buy some.” According to Canwest, Bruce Cran, president of the Consumers Association of Canada, said he was getting calls in British Columbia that store shelves were being emptied of rice by panicked buyers: “I was in one of the national chains and there was one packet of rice left on the shelf.” And, predictably, this panic buying led to even higher prices as it shifted the demand curve rightward, further feeding the buying frenzy. As one market owner said, “People are afraid. We tell them, ‘There’s no shortage yet’ but it was crazy in here.”

Quick Review

Changes in the equilibrium price and quantity in a market result from shifts of the supply curve, the demand curve, or both.

An increase in demand increases both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity. A decrease in demand decreases both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity.

An increase in supply drives the equilibrium price down but increases the equilibrium quantity. A decrease in supply raises the equilibrium price but reduces the equilibrium quantity.

Often fluctuations in markets involve shifts of both the supply and demand curves. When they shift in the same direction, the change in equilibrium quantity is predictable but the change in equilibrium price is not. When they shift in opposite directions, the change in equilibrium price is predictable but the change in equilibrium quantity is not. When there are simultaneous shifts of the demand and supply curves, the curve that shifts the greater distance has a greater effect on the change in equilibrium price and quantity.

Check Your Understanding 3-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 3-4

Question 3.4

In each of the following examples, determine (i) the market in question; (ii) whether a shift in demand or supply occurred, the direction of the shift, and what induced the shift; and (iii) the effect of the shift on the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity.

As the price of gasoline fell in Canada during the 1990s, more people bought large cars.

As technological innovation has lowered the cost of recycling used paper, fresh paper made from recycled stock is used more frequently.

When a local cable company offers cheaper on-demand films, local movie theatres have more unfilled seats.

The market for large cars: this is a rightward shift in demand caused by a decrease in the price of a complement, gasoline. As a result of the shift, the equilibrium price of large cars will rise and the equilibrium quantity of large cars bought and sold will also rise.

The market for fresh paper made from recycled stock: this is a rightward shift in supply due to a technological innovation. As a result of this shift, the equilibrium price of fresh paper made from recycled stock will fall and the equilibrium quantity bought and sold will rise.

The market for movies at a local movie theatre: this is a leftward shift in demand caused by a fall in the price of a substitute, on-demand films. As a result of this shift, the equilibrium price of movie tickets will fall and the equilibrium number of people who go to the movies will also fall.

Question 3.5

When a new, faster computer chip is introduced, demand for computers using the older, slower chips decreases. Simultaneously, computer makers increase their production of computers containing the old chips in order to clear out their stocks of old chips.

Draw two diagrams of the market for computers containing the old chips:

one in which the equilibrium quantity falls in response to these events and

one in which the equilibrium quantity rises.

What happens to the equilibrium price in each diagram?

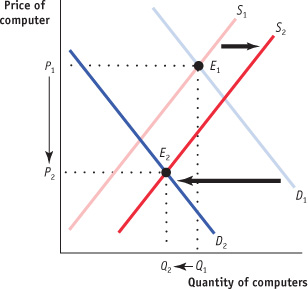

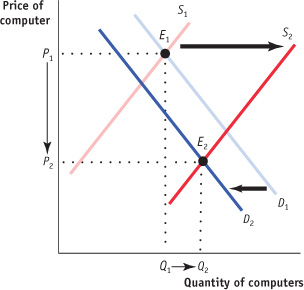

Upon the announcement of the new chip, the demand curve for computers using the earlier chip shifts leftward, as demand decreases, and the supply curve for these computers shifts rightward, as supply increases.

If demand decreases relatively more than supply increases, then the equilibrium quantity falls, as shown here:

If supply increases relatively more than demand decreases, then the equilibrium quantity rises, as shown here:

In both cases, the equilibrium price falls.