8.3 The Effects of Trade Protection

Ever since David Ricardo laid out the principle of comparative advantage in the early nineteenth century, most economists have advocated free trade. That is, they have argued that government policy should not attempt either to reduce or to increase the levels of exports and imports that occur naturally as a result of supply and demand. Despite the free-

An economy has free trade when the government does not attempt either to reduce or to increase the levels of exports and imports that occur naturally as a result of supply and demand.

Let’s look at the two most common protectionist policies, tariffs and import quotas, then turn to the reasons governments follow these policies.

Policies that limit imports are known as trade protection or simply as protection.

The Effects of a Tariff

A tariff is a tax levied on imports.

A tariff is a form of excise tax, one that is levied only on sales of imported goods. For example, the Canadian government could declare that anyone bringing in auto seats must pay a tariff of $100 per unit. In the distant past, tariffs were an important source of government revenue because they were relatively easy to collect. But in the modern world, tariffs are usually intended to discourage imports and protect import-

The tariff raises both the price received by domestic producers and the price paid by domestic consumers. Suppose, for example, that our country imports auto seats, and an auto seat costs $200 on the world market. As we saw earlier, under free trade the domestic price would also be $200. But if a tariff of $100 per unit is imposed, the domestic price will rise to $300, because it won’t be profitable to import auto seats unless the price in the domestic market is high enough to compensate importers for the cost of paying the tariff.

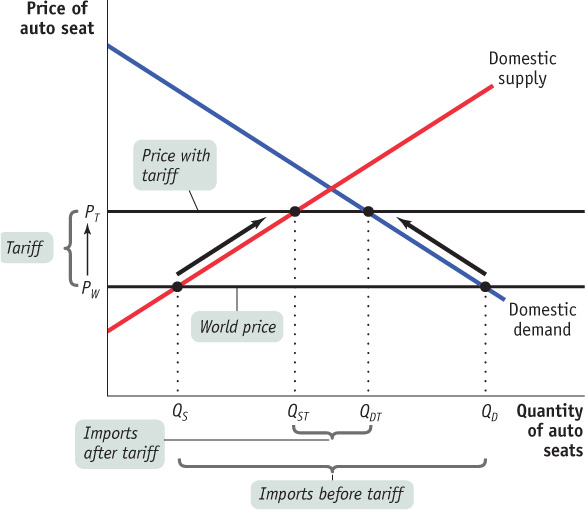

Figure 8-10 illustrates the effects of a tariff on imports of auto seats. As before, we assume that PW is the world price of an auto seat. Before the tariff is imposed, imports have driven the domestic price down to PW, so that pre-

Now suppose that the government imposes a tariff on each auto seat imported. As a consequence, it is no longer profitable to import auto seats unless the domestic price received by the importer is greater than or equal to the world price plus the tariff. So the domestic price rises to PT, which is equal to the world price, PW, plus the tariff. Domestic production rises to QST, domestic consumption falls to QDT, and imports fall to QDT − QST.

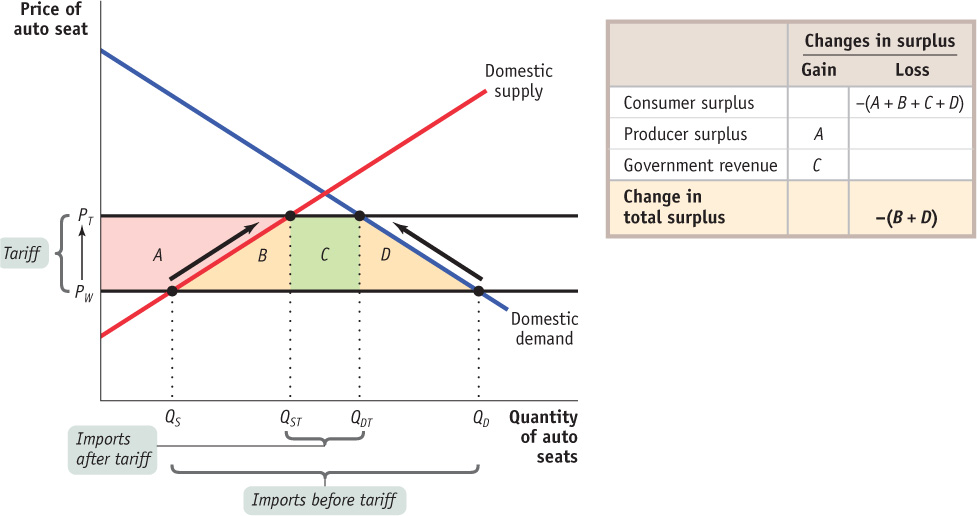

A tariff, then, raises domestic prices, leading to increased domestic production and reduced domestic consumption compared to the situation under free trade. Figure 8-11 shows the effects on surplus. There are three effects:

The higher domestic price increases producer surplus, a gain equal to area A.

The higher domestic price reduces consumer surplus, a reduction equal to the sum of areas A, B, C, and D.

The tariff yields revenue to the government. How much revenue? The government collects the tariff—

which, remember, is equal to the difference between PT and PW on each of the QDT − QST units imported. So total revenue is (PT − PW) × (QDT − QST). This is equal to area C.

The welfare effects of a tariff are summarized in the table in Figure 8-11. Producers gain, consumers lose, and the government gains. But consumer losses are greater than the sum of producer and government gains, leading to a net reduction in total surplus equal to areas B + D.

An excise tax creates inefficiency, or deadweight loss, because it prevents mutually beneficial trades from occurring. The same is true of a tariff, where the deadweight loss imposed on society is equal to the loss in total surplus represented by areas B + D.

Tariffs generate deadweight losses because they create inefficiencies in two ways:

Some mutually beneficial trades go unexploited: some consumers who are willing to pay more than the world price, PW, do not purchase the good, even though PW is the true cost of a unit of the good to the economy. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 8-11 by area D.

The economy’s resources are wasted on inefficient production: some producers whose cost exceeds PW produce the good, even though an additional unit of the good can be purchased abroad for PW. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 8-11 by area B.

The Effects of an Import Quota

An import quota, another form of trade protection, is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported. For example, a Canadian import quota on Mexican auto seats might limit the quantity imported each year to 50 000 units. Import quotas are usually administered through licences: a number of licences are issued, each giving the licence-holder the right to import a limited quantity of the good each year.

An import quota is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported.

A quota on sales has the same effect as an excise tax, with one difference: the money that would otherwise have accrued to the government as tax revenue under an excise tax becomes licence-holders’ revenue under a quota—also known as quota rents. (“Quota rent” was defined in Chapter 5.) Similarly, an import quota has the same effect as a tariff, with one difference: the money that would otherwise have been government revenue becomes quota rents to licence-holders. Look again at Figure 8-11. An import quota that limits imports to QDT − QST will raise the domestic price of auto parts by the same amount as the tariff we considered previously. That is, it will raise the domestic price from PW to PT. However, area C will now represent quota rents rather than government revenue.

Who receives import licences and so collects the quota rents? In the case of Canadian import protection, the answer may surprise you: the most important import licences—mainly for textiles and clothing—are granted to foreign governments.

Because the quota rents for most Canadian import quotas go to foreigners, the cost to Canada of such quotas is larger than that of a comparable tariff (a tariff that leads to the same level of imports). In Figure 8-11, the net loss to Canada from such an import quota would be equal to areas B + C + D, the difference between consumer losses and producer gains.

When a country imposes trade barriers (import tariffs or import quotas), it has economic impacts on foreign countries. Both types of barriers, in effect, raise the price of foreign products in the importing country and lower the domestic demand for foreign goods. This reduction of domestic demand for foreign goods could lead to job losses and reduced export revenues in foreign countries. In the case of poor or developing countries, the impact of such barriers on their exports may have profound negative effects on their economies.

TRADE PROTECTION IN CANADA

Canada was created as a nation by the British North America Act of 1867. At that time, Canada’s western provinces were barely settled, most of the country’s trading links were north–south, there was no transcontinental railway, and Canada’s fledgling manufacturing industry faced stiff competition from the United States and Britain.

In an attempt to forge Canada’s small, diverse, and far-flung people into a single nation, the government of Sir John A. Macdonald implemented a “National Policy” in 1879. This policy had several pillars. It involved encouraging western settlement with homestead grants of free land. It involved building a transcontinental railway to transport manufactured goods from the East and to route food from the West. And, most significantly, it involved a system of high tariffs designed to protect and promote Canadian manufacturing. The aim of the National Policy was to replace existing north–south trading relationships with newly created east–west ones, to create a national market, and to achieve a truly east–west transcontinental union. The tariffs were part of this nation-building enterprise.

Since then, Canada and its infant industries have grown up. In 1947, Canada and 22 other countries signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) with the aim of reducing trade barriers. Successive waves of negotiations resulted in additional rounds of GATT, the most notable being the Uruguay Round, completed in 1994. This round had success on four broad fronts. First, it succeeded in reducing world tariffs by about 40%. Second, while Canada and the European Union (EU) prevented an agreement on liberalizing trade in agricultural goods, both were forced to replace agricultural quotas with “tariff equivalents.” Those countries pushing for free trade in agricultural goods hoped that pressure would build for reduction of the high tariffs over subsequent decades. Third, quotas restricting trade in textiles and garments had to be phased out over a 10-year period ending January 1, 2005. Fourth, and perhaps most significant, the Uruguay Round eliminated the GATT structure and replaced it with the World Trade Organization (WTO), which has a formal dispute settlement mechanism and whose rulings are binding on member governments.

Besides these multilateral agreements toward trade liberalization, Canada has also negotiated separately with the United States. In 1989 Canada and the United States signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), and in 1994 the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) extended the original agreement to include Mexico.

In recent years, Canada has negotiated with the EU toward a comprehensive economic and trade agreement (CETA), a very ambitious trade initiative because of the size of the EU. These trade negotiations covered many sectors, from agricultural to manufacturing, from the lumber industry to the information technology industry. Even though it is not easy to enter into such an agreement (since it is very difficult for countries to reach consensus on the various issues), Canada and the EU finally signed a free trade agreement in principle on October 18, 2013. For the deal to start in 2015, it requires ratification by all Canadian provinces and territories and all EU member countries. Once the CETA is implemented, most tariffs between Canada and the EU will be eliminated.

Canada today generally follows a policy of free trade, at least in comparison with other countries and in comparison with its own past. Most manufactured goods are subject to either no tariff or a low tariff. However, Canada does still limit imports of many agricultural goods, textiles, and clothing, and has export controls on some agricultural products and strategic goods. According to the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development, the federal department that is responsible for issues related to Canada’s international trade, import and export controls are justified for the following reasons:

To protect national security

To protect domestic industries that are deemed strategic or vulnerable

To fulfill other international obligations

To implement United Nations Security Council trade sanctions

Quick Review

Most economists advocate free trade, although many governments engage in trade protection of import-competing industries. The two most common protectionist policies are tariffs and import quotas. In rare instances, governments subsidize exporting industries.

A tariff is a tax on imports. It raises the domestic price above the world price, leading to a fall in trade and domestic consumption and a rise in domestic production. Domestic producers and the government gain, but domestic consumer losses more than offset this gain, leading to deadweight loss.

An import quota is a legal quantity limit on imports. Its effect is like that of a tariff, except that revenues—the quota rents—accrue to the licence-holder, not to the domestic government.

Check Your Understanding 8-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 8-3

Question 8.5

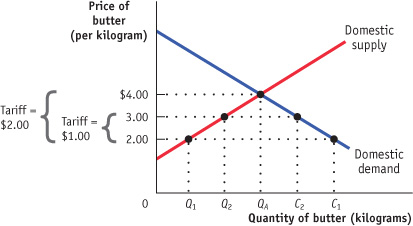

Suppose the world price of butter is $2.00 per kilogram and the domestic price in autarky is $4.00 per kilogram. Use a diagram similar to Figure 8-10 to show the following.

If there is free trade, domestic butter producers want the government to impose a tariff of no less than $2.00 per kilogram.

A tariff greater than $2.00 per kilogram is imposed.

If the tariff is $2.00, the price paid by domestic consumers for a kilogram of imported butter is $2.00 + $2.00 = $4.00, the same price as a kilogram of domestic butter. Imported butter will no longer have a price advantage over domestic butter, imports will cease, and domestic producers will capture all the feasible sales to domestic consumers, selling amount QA in the accompanying figure. But if the tariff is less than $2.00—say, only $1.00—the price paid by domestic consumers for a kilogram of imported butter is $2.00 + $1.00 = $3.00, $1.00 cheaper than a kilogram of domestic butter. Canadian butter producers will gain sales in the amount of Q2 − Q1 as a result of the $1.00 tariff. But this is smaller than the amount they would have gained under the $2.00 tariff, the amount QA − Q1.

As long as the tariff is at least $2.00, increasing it more has no effect. At a tariff of $2.00, all imports are effectively blocked.

Question 8.6

Suppose the government imposes an import quota rather than a tariff on butter. What quota limit would generate the same quantity of imports as a tariff of $2.00 per kilogram?

All imports are effectively blocked at a tariff of $2.00. So such a tariff corresponds to an import quota of 0.