3. The Division of Labor

Printed Page 157

Testimony Gathered by Ashley’s Mines Commission (1842)and

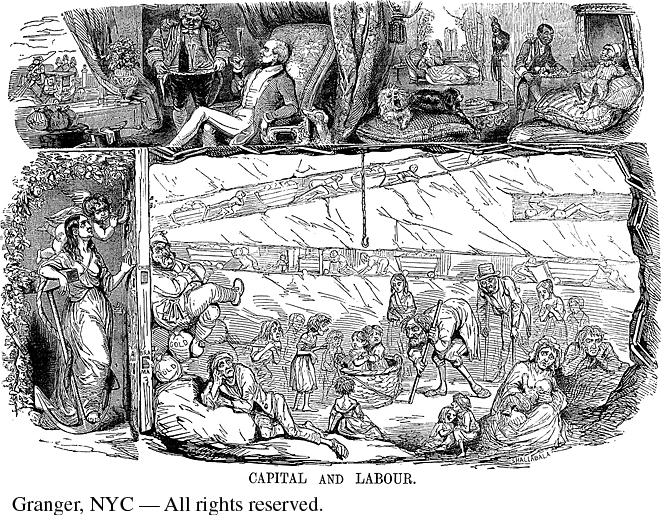

Punch Magazine, “Capital and Labour” (1843)

Coal-fired steam engines were at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. They fueled the rapid spread of railroads and new textile machinery, which in turn fueled an increased demand for coal. Miners, young and old, worked under extremely difficult conditions to keep pace. This was especially true in Britain, the hub of the Industrial Revolution, where the output of coal and iron doubled between 1830 and 1850. The miners’ plight sparked calls for reform, with the government often taking the lead. In 1842, Anthony Ashley Cooper headed a series of parliamentary hearings to gather firsthand accounts of the working conditions in the mines, particularly regarding the use of child labor. Below are excerpts from testimony heard by the commission describing the dismal realities of the mining industry. The “Capital and Labour” cartoon appeared in the British magazine Punch the following year to coincide with Parliament’s ongoing investigation into the employment of children in the workplace. As it suggests, people recognized not only that industrialization was built on the backs of workers but also that it profoundly altered traditional socioeconomic relations, with capitalistic “money men” exploiting human labor for monetary gain.

From Jonathan F. Scott and Alexander Baltzly, Readings in European History Since 1814 (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1958), 87–90; and Michael Freeman, Railways and the Victorian Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), plate 108. © Punch Magazine, 1843.

Sarah Gooder, Aged 8 Years

I’m a trapper1 in the Gawber pit. It does not tire me, but I have to trap without a light and I’m scared. I go at four and sometimes half past three in the morning, and come out at five and half past. I never go to sleep. Sometimes I sing when I’ve light, but not in the dark; I dare not sing then. I don’t like being in the pit. I am very sleepy when I go sometimes in the morning. I go to Sunday-schools and read Reading Made Easy. She knows her letters and can read little words. They teach me to pray. She repeated the Lord’s Prayer, not very perfectly, and ran on with the following addition:—“God bless my father and mother, and sister and brother, uncles and aunts and cousins, and everybody else, and God bless me and make me a good servant. Amen.” I have heard tell of Jesus many a time. I don’t know why he came on earth, I’m sure, and I don’t know why he died, but he had stones for his head to rest on. I would like to be at school far better than in the pit.

Thomas Wilson, Esq., of the Banks, Silkstone, Owner of Three Collieries2

. . . The employment of females of any age in and about the mines is most objectionable, and I should rejoice to see it put an end to; but in the present feeling of the colliers, no individual would succeed in stopping it in a neighbourhood where it prevailed, because the men would immediately go to those pits where their daughters would be employed. The only way effectually to put an end to this and other evils in the present colliery system is to elevate the minds of the men; and the only means to attain this is to combine sound moral and religious training and industrial habits with a system of intellectual culture much more perfect than can at present be obtained by them.

I object on general principles to government interference in the conduct of any trade, and I am satisfied that in mines it would be productive of the greatest injury and injustice. The art of mining is not so perfectly understood as to admit of the way in which a colliery shall be conducted being dictated by any person, however experienced, with such certainty as would warrant an interference with the management of private business. I should also most decidedly object to placing collieries under the present provisions of the Factory Act with respect to the education of children employed therein. First, because, if it is contended that coal-owners, as employers of children, are bound to attend to their education, this obligation extends equally to all other employers, and therefore it is unjust to single out one class only; secondly, because, if the legislature asserts a right to interfere to secure education, it is bound to make that interference general; and thirdly, because the mining population is in this neighbourhood so intermixed with other classes, and is in such small bodies in any one place, that it would be impossible to provide separate schools for them.

Isabella Read, 12 Years Old, Coal-Bearer

Works on mother’s account, as father has been dead two years. Mother bides at home, she is troubled with bad breath, and is very weak in her body from early labour. I am wrought with sister and brother, it is very sore work; cannot say how many rakes or journeys I make from pit’s bottom to wall face and back, thinks about 30 or 25 on the average; the distance varies from 100 to 250 fathom.

I carry about 1 cwt.3 and a quarter on my back; have to stoop much and creep through water, which is frequently up to the calves of my legs. When first down fell frequently asleep while waiting for coal from heat and fatigue.

I do not like the work, nor do the lassies, but they are made to like it. When the weather is warm there is difficulty in breathing, and frequently the lights go out.

Isabel Wilson, 38 Years Old, Coal Putter [hauler]

When women have children thick (fast) they are compelled to take them down early, I have been married 19 years and have had 10 bairns; seven are in life. When on Sir John’s work was a carrier of coals, which caused me to miscarry five times from the strains, and was ill after each. Putting is not so oppressive; last child was born on Saturday morning, and I was at work on the Friday night.

Once met with an accident; a coal brake my cheek-bone, which kept me idle some weeks.

I have wrought below 30 years, and so has the guid man; he is getting touched in the breath now.

None of the children read, as the work is not regular. I did read once, but not able to attend to it now; when I go below lassie 10 years of age keeps house and makes the broth or stir-about.

Nine sleep in two bedsteads; there did not appear to be any beds, and the whole of the other furniture consisted of two chairs, three stools, a table, a kail-pot and a few broken basins and cups. Upon asking if the furniture was all they had, the guid wife said, furniture was of no use, as it was so troublesome to flit with.

Patience Kershaw, Aged 17

My father has been dead about a year; my mother is living and has ten children, five lads and five lasses; the oldest is about thirty, the youngest is four; three lasses go to mill; all the lads are colliers, two getters and three hurriers4; one lives at home and does nothing; mother does nought but look after home.

All my sisters have been hurriers, but three went to the mill. Alice went because her legs swelled from hurrying in cold water when she was hot. I never went to day-school; I go to Sunday-school, but I cannot read or write; I go to pit at five o’clock in the morning and come out at five in the evening; I get my breakfast of porridge and milk first; I take my dinner with me, a cake, and eat it as I go; I do not stop or rest any time for the purpose; I get nothing else until I get home, and then have potatoes and meat, not every day meat. I hurry in the clothes I have now got on, trousers and ragged jacket; the bald place upon my head is made by thrusting the corves; my legs have never swelled, but sisters’ did when they went to mill; I hurry the corves a mile and more under ground and back; they weigh 300 cwt.; I hurry 11 a-day; I wear a belt and chain at the workings to get the corves out; the getters that I work for are naked except their caps; they pull off all their clothes; I see them at work when I go up; sometimes they beat me, if I am not quick enough, with their hands; they strike me upon my back; the boys take liberties with me sometimes they pull me about; I am the only girl in the pit; there are about 20 boys and 15 men; all the men are naked; I would rather work in mill than in coal-pit.

This girl is an ignorant, filthy, ragged, and deplorable-looking object, and such an one as the uncivilized natives of the prairies would be shocked to look upon.

Mary Barrett, Aged 14

I have worked down in pit five years; father is working in next pit; I have 12 brothers and sisters—all of them but one live at home; they weave, and wind, and hurry, and one is a counter, one of them can read, none of the rest can, or write; they never went to day-school, but three of them go to Sunday-school; I hurry for my brother John, and come down at seven o’clock about; I go up at six, sometimes seven; I do not like working in pit, but I am obliged to get a living; I work always without stockings, or shoes, or trousers; I wear nothing but my chemise; I have to go up to the headings with the men; they are all naked there; I am got well used to that, and don’t care now much about it; I was afraid at first, and did not like it; they never behave rudely to me; I cannot read or write.

Capital and Labour

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How does the top portion of the cartoon portray the lifestyle of British capitalists? What images stand out in particular?

Question

How does the top portion of the cartoon portray the lifestyle of British capitalists? What images stand out in particular?

accept_blank_answers: true

points: 10How does the top portion of the cartoon portray the lifestyle of British capitalists? What images stand out in particular? - How does this portrait contrast to that of the people shown in the bottom portion? What connections do you see between the images here and the testimony gathered by Ashley’s Mines Commission?

Question

How does this portrait contrast to that of the people shown in the bottom portion? What connections do you see between the images here and the testimony gathered by Ashley’s Mines Commission?

accept_blank_answers: true

points: 10How does this portrait contrast to that of the people shown in the bottom portion? What connections do you see between the images here and the testimony gathered by Ashley’s Mines Commission? - What is the relationship between the top and bottom parts of the cartoon? How are their meanings interdependent?

Question

What is the relationship between the top and bottom parts of the cartoon? How are their meanings interdependent?

accept_blank_answers: true

points: 10What is the relationship between the top and bottom parts of the cartoon? How are their meanings interdependent?