5. Artistic Expression

Printed Page 200

Edgar Degas, Notebooks (1863–1884)

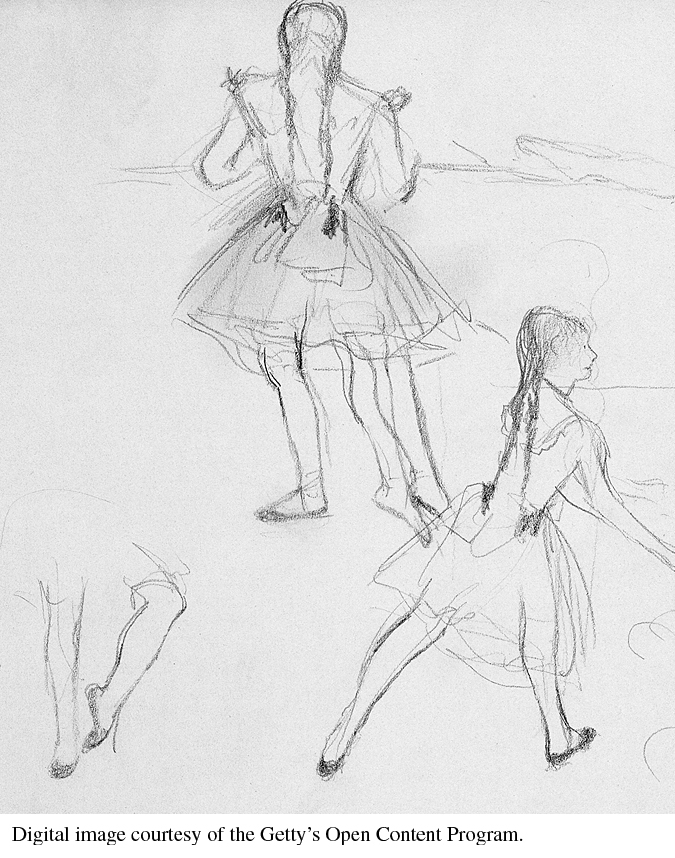

Visual artists were not immune to the changes unfolding around them in late-nineteenth-century Europe. Beginning in the 1850s, many artists turned away from classical and romantic conventions and portrayed the world in realistic and graphic ways. Some artists pushed the boundaries of tradition further still with a new style called impressionism. Impressionists were equally fascinated with their immediate surroundings but also focused on the light, color, and movement of a single moment. Edgar Degas (1834–1917) embodied this shift in the visual arts. A classically trained draftsman, Degas began his professional career in Paris in 1859, painting portraits and historical subjects. For Degas, the pull of convention was ultimately no match for the novel artistic influences energizing the Parisian art scene at the time, notably Japanese prints, photography, and the fledgling impressionist movement. The impact on Degas was profound. By the late 1860s, he had turned his eye to depicting modern life in motion. The excerpts and pencil drawing of ballet dancers rehearsing from his private notebooks capture his artistic creativity and driving desire to portray local scenes and individuals one moment and one action at a time.

From Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 1874-1904, 1st Ed., edited by Linda Nochlin. © 1966, pp.61-63. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., New York, New York.

From Degas’ Notebook: 1863–1867

What is certain is that putting a bit of nature in place and drawing it are two entirely different things.1

I don’t like to hear people saying like children in front of rosy and glowing flesh: “Oh, what life, what blood!”—the human skin is as varied in appearance, especially among us, as the rest of nature: fields, trees, mountains, water, forests. It is possible to meet with as many resemblances between a face and a pebble as between two pebbles because everyone still wants to see a likeness between two faces. (I am speaking in terms of the question of form, not bringing up that of coloring, since we often find so much connection between a pebble and a fish, a mountain and a dog’s head, clouds and horses, etc.)

Therefore, it is not merely instinct which makes us say that we must search for a method of coloring everywhere, for the affinities among what is alive, what is dead and what vegetates. I can, for example, easily recall the color of some hair, because I got the idea that it was hair made out of polished walnutwood, or else flax, or horse-chestnut shells. The rendering of the form will make real hair, with its softness and lightness or its roughness or its weight out of this tone which is almost precisely that of walnutwood, flax, or horse-chestnut shell. And then one paints in such different ways on such different supports that the same tone might be one thing in one place, another in another. . . .

From Degas’ Notebook: 1878–1884

After having done portraits seen from above, I will do them seen from below—sitting very close to a woman and looking at her from a low viewpoint, I will see her head in the chandelier, surrounded by crystals, etc.; do simple things like draw a profile which would not move, [the painter] himself moving, going up or down, the same for a full face—a piece of furniture, a whole living room; do a series of arm-movements of the dance, or of legs that would not move, himself turning either around or—etc. Finally study a figure or an object, no matter what, from every viewpoint. One could use a looking glass for that, one would not [have to] stir from one’s place. Only the looking glass would be lowered or tilted. One would turn about. Studio projects: Set up tiers [a series of benches] all around the room so as to get used to drawing things from above and below. Only let myself paint things seen in a looking glass to get used to hatred of trompe-l’oeil.2

For a portrait, make someone pose on the ground floor and work on the first floor to get used to keeping hold of the forms and expressions and never draw or paint immediately.

For the Newspaper cut a lot. Of a dancer do either the arms or the legs or the back. Do the shoes—the hands—of the hairdresser—the badly cut coiffure . . ., bare feet in dance, action, etc., etc.

Do every kind of worn object placed, accompanied in such a way that they have the life of the man or the woman; corsets which have just been taken off, for example—and which keep the form of the body, etc., etc.

Series on instruments and instrumentalists, their shapes, twisting of the hands and arms and neck of the violinist, for example, puffing out and hollowing of the cheeks of bassoons, oboes, etc.

Do a series in aquatint on mourning (different blacks), black veils of deep mourning (floating on the face), black gloves, carriages in mourning, carriage of the Funeral Company, carriages like Venetian gondolas.

On smoke, smoke of smokers, pipes, cigarettes, cigars, smoke of locomotives, of high chimneys, factories, steamboats, etc. Destruction of smoke under the bridges. Steam.

On the evening. Infinite subjects. In the cafés, different values of the glass-shades reflected in the mirrors.

On the bakery, the bread: series on journeymen bakers, seen in the cellar itself or through the air vents from the street. Colors of pink flour—lovely curves of pie, still lifes on the different breads, large, oval, fluted, round, etc. Experiment, in color, on the yellows, pinks, grey-whites of breads. Perspective views of rows of breads. Charming layout of bakeries. Cakes, the wheat, the mills, the flour, the sacks, the market-porters.

No one has ever done monuments or houses from below, from beneath, up close as one sees them going by in the streets.

Ballet Dancers Rehearsing: 1877

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What subjects intrigued Degas as an artist? Why was he interested in portraying them from so many different viewpoints and positions? How does this interest find visual expression in the pencil sketch?

Question

What subjects intrigued Degas as an artist? Why was he interested in portraying them from so many different viewpoints and positions? How does this interest find visual expression in the pencil sketch?

accept_blank_answers: true

points: 10What subjects intrigued Degas as an artist? Why was he interested in portraying them from so many different viewpoints and positions? How does this interest find visual expression in the pencil sketch? - Although Degas disliked the label “impressionist,” what evidence do you see of impressionism’s influence on his ideas about visual art?

Question

Although Degas disliked the label “impressionist,” what evidence do you see of impressionism’s influence on his ideas about visual art?

accept_blank_answers: true

points: 10Although Degas disliked the label “impressionist,” what evidence do you see of impressionism’s influence on his ideas about visual art? - How did the changing economic and social scene in Paris at the time influence Degas’ interests and approach?

Question

How did the changing economic and social scene in Paris at the time influence Degas’ interests and approach?

accept_blank_answers: true

points: 10How did the changing economic and social scene in Paris at the time influence Degas’ interests and approach?