The Structure of the Proposal

Proposal structures vary greatly from one organization to another. A long, complex proposal might have 10 or more sections, including introduction, problem, objectives, solution, methods and resources, and management. If the authorizing agency provides an IFB, an RFP, an RFQ, or a set of guidelines, follow it closely. If you have no guidelines, or if you are writing an unsolicited proposal, use the structure shown here as a starting point. Then modify it according to your subject, your purpose, and the needs of your audience. An example of a proposal is presented later in the chapter.

For more about summaries, see “Writing Recommendation Reports” in Ch. 13.

SUMMARY

For a proposal of more than a few pages, provide a summary. Many organizations impose a length limit—such as 250 words—and ask the writer to present the summary, single-spaced, on the title page. The summary is crucial, because it might be the only item that readers study in their initial review of the proposal.

The summary covers the major elements of the proposal but devotes only a few sentences to each. Define the problem in a sentence or two. Next, describe the proposed program and provide a brief statement of your qualifications and experience. Some organizations wish to see the completion date and the final budget figure in the summary; others prefer that this information be presented separately on the title page along with other identifying information about the supplier and the proposed project.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of the introduction is to help readers understand the context, scope, and organization of the proposal.

PROPOSED PROGRAM

In the section on the proposed program, sometimes called the plan of work, explain what you want to do. Be specific. You won’t persuade anyone by saying that you plan to “gather the data and analyze it.” How will you gather and analyze the data? Justify your claims. Every word you say—or don’t say—will give your readers evidence on which to base their decision.

If your project concerns a subject written about in the professional literature, show your familiarity with the scholarship by referring to the pertinent studies. However, don’t just string together a bunch of citations. For example, don’t write, “Carruthers (2012), Harding (2013), and Vega (2013) have all researched the relationship between global warming and groundwater contamination.” Rather, use the recent literature to sketch the necessary background and provide the justification for your proposed program. For instance:

“Carruthers (2012), Harding (2013), and Vega (2013) have demonstrated the relationship between global warming and groundwater contamination. None of these studies, however, included an analysis of the long-term contamination of the aquifer. The current study will consist of . . . .

Introducing a Proposal

The introduction to a proposal should answer the following seven questions:

What is the problem or opportunity? Describe the problem or opportunity in specific monetary terms, because the proposal itself will include a budget, and you want to convince your readers that spending money on what you propose is smart. Don’t say that a design problem is slowing down production; say that it is costing $4,500 a day in lost productivity.

What is the purpose of the proposal? The purpose of the proposal is to describe a solution to a problem or an approach to an opportunity and propose activities that will culminate in a deliverable. Be specific in explaining what you want to do.

What is the background of the problem or opportunity? Although you probably will not be telling your readers anything they don’t already know, show them that you understand the problem or opportunity: the circumstances that led to its discovery, the relationships or events that will affect the problem and its solution, and so on.

What are your sources of information? Review the relevant literature, ranging from internal reports and memos to published articles or even books, so that readers will understand the context of your work.

What is the scope of the proposal? If appropriate, indicate not only what you are proposing to do but also what you are not proposing to do.

What is the organization of the proposal? Explain the organizational pattern you will use.

What are the key terms that you will use in the proposal? If you will use any specialized or unusual terms, define them in the introduction.

For more about researching a subject, see Ch. 5.

You might include only a few references to recent research. However, if your topic is complex, you might devote several paragraphs or even several pages to recent scholarship.

Whether your project calls for primary research, secondary research, or both, the proposal will be unpersuasive if you haven’t already done a substantial amount of research. For instance, say you are writing a proposal to do research on purchasing new industrial-grade lawn mowers for your company. Simply stating that you will visit Wal-Mart, Lowe’s, and Home Depot to see what kinds of lawn mowers they carry would be unpersuasive for two reasons:

You need to justify why you are going to visit those three retailers rather than others. Anticipate your readers’ questions: Why did you choose these three retailers? Why didn’t you choose specialized dealers?

- Page 304You should already have determined what stores carry what kinds of lawn mowers and completed any other preliminary research. If you haven’t done the homework, readers have no assurance that you will in fact do it or that it will pay off. If your supervisor authorizes the project and then you learn that none of the lawn mowers in these stores meets your organization’s needs, you will have to go back and submit a different proposal—an embarrassing move.

Unless you can show in your proposed program that you have done the research—and that the research indicates that the project is likely to succeed—the reader has no reason to authorize the project.

QUALIFICATIONS AND EXPERIENCE

After you have described how you would carry out the project, show that you can do it. The more elaborate the proposal, the more substantial the discussion of your qualifications and experience has to be. For a small project, include a few paragraphs describing your technical credentials and those of your co-workers. For larger projects, include the résumés of the project leader, often called the principal investigator, and the other primary participants.

External proposals should also discuss the qualifications of the supplier’s organization, describing similar projects the supplier has completed successfully. For example, a company bidding on a contract to build a large suspension bridge should describe other suspension bridges it has built. It should also focus on the equipment and facilities the company already has and on the management structure that will ensure the project will go smoothly.

BUDGET

Good ideas aren’t good unless they’re affordable. The budget section of a proposal specifies how much the proposed program will cost.

Budgets vary greatly in scope and format. For simple internal proposals, add the budget request to the statement of the proposed program: “This study will take me two days, at a cost of about $400” or “The variable-speed recorder currently costs $225, with a 10 percent discount on orders of five or more.” For more-complicated internal proposals and for all external proposals, include a more-explicit and complete budget.

Many budgets are divided into two parts: direct costs and indirect costs. Direct costs include such expenses as salaries and fringe benefits of program personnel, travel costs, and costs of necessary equipment, materials, and supplies. Indirect costs cover expenses that are sometimes called overhead: general secretarial and clerical expenses not devoted exclusively to any one project, as well as operating expenses such as costs of utilities and maintenance. Indirect costs are usually expressed as a percentage—ranging from less than 20 percent to more than 100 percent—of the direct expenses.

APPENDIXES

Many types of appendixes might accompany a proposal. Most organizations have boilerplate descriptions of the organization and of the projects it has completed. Another item commonly included in an appendix is a supporting letter: a testimonial to the supplier’s skill and integrity, written by a reputable and well-known person in the field. Two other kinds of appendixes deserve special mention: the task schedule and the description of evaluation techniques.

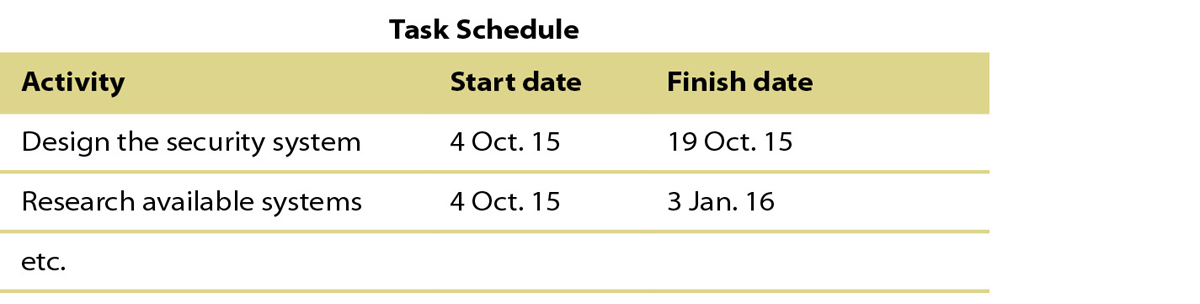

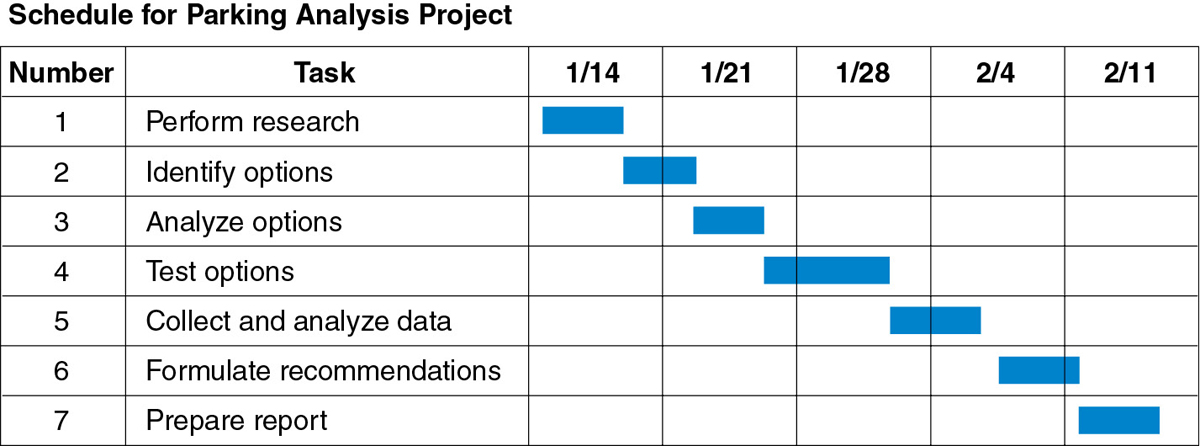

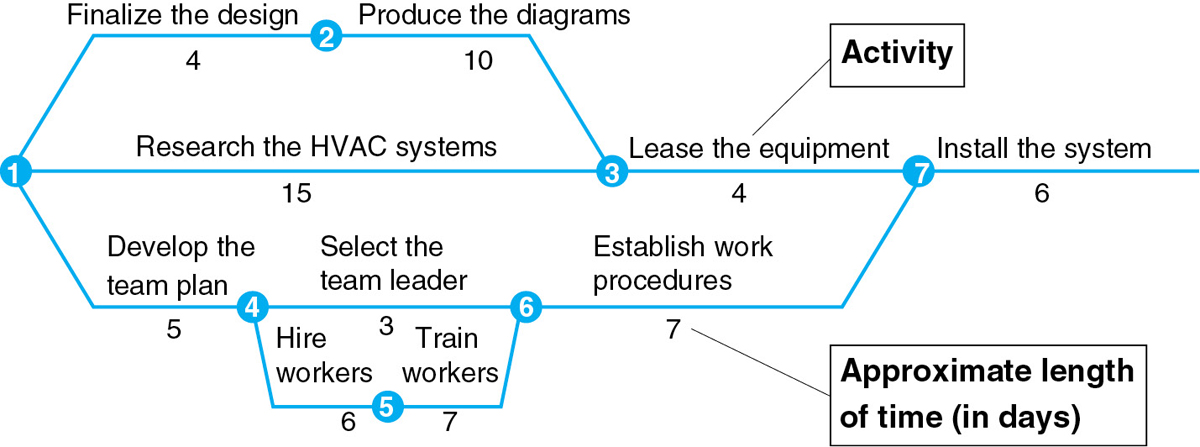

Task Schedule A task schedule is almost always presented in one of three graphical formats: as a table, a bar chart, or a network diagram.

Tables The simplest but least informative way to present a schedule is in a table, as shown in Figure 11.3. As with all graphics, provide a textual reference that introduces and, if necessary, explains the table.

Although displaying information in a table is better than writing it out in sentences, readers still cannot “see” the information. They have to read the table to figure out how long each activity will last, and they cannot tell whether any of the activities are interdependent. They have no way of determining what would happen to the overall project schedule if one of the activities faced delays.

Bar Charts Bar charts, also called Gantt charts after the early twentieth-century civil engineer who first used them, are more informative than tables. The basic bar chart shown in Figure 11.4 allows readers to see how long each task will take and whether different tasks will occur simultaneously. Like tables, however, bar charts do not indicate the interdependence of tasks.

Network diagrams Network diagrams show interdependence among various activities, clearly indicating which must be completed before others can begin. However, even a relatively simple network diagram, such as the one shown in Figure 11.5, can be difficult to read. You would probably not use this type of diagram in a document intended for general readers.

Description of Evaluation Techniques Although evaluation can mean different things to different people, an evaluation technique typically refers to any procedure used to determine whether the proposed program is both effective and efficient. Evaluation techniques can range from writing simple progress reports to conducting sophisticated statistical analyses. Some proposals call for evaluation by an outside agent, such as a consultant, a testing laboratory, or a university. Other proposals describe evaluation techniques that the supplier will perform, such as cost-benefit analyses.

The issue of evaluation is complicated by the fact that some people think in terms of quantitative evaluations—tests of measurable quantities, such as production increases—whereas others think in terms of qualitative evaluations—tests of whether a proposed program is improving, say, the workmanship on a product. And some people include both qualitative and quantitative testing when they refer to evaluation. An additional complication is that projects can be tested while they are being carried out (formative evaluations) as well as after they have been completed (summative evaluations).

When an RFP calls for “evaluation,” experienced proposal writers contact the prospective customer to determine precisely what the word means.