Chapter 8. How Would You Know If Our Memory is Accurate?

8.1

By:

C. Nathan DeWall, University of Kentucky

David G. Myers, Hope College

8.2

Note: You will be guided through the Intro, Design, Measure, Interpret, Conclusion, and Quiz sections of this activity. You can see your progress highlighted in the non-clickable, navigational list at right.

Watch this video from your author, Nathan DeWall, for a helpful, very brief overview of the activity.

8.3

So, how would you know if our memory is accurate? To study this question in your role as researcher, you need to DESIGN an appropriate study that will lead to meaningful results, MEASURE memory accuracy, and INTERPRET the larger meaning of your results, considering how your findings would apply to the population as a whole.

Question

Click on "Video Hint" below to see brief animations describing Case Studies, Correlational Studies, and Experiments.

Video Hint

8.4

Case Studies:

Correlational Studies:

Experiments:

8.5

You have chosen Case Study as your design. With a Case Study design, you will choose one person or a small group of people, such as those with unusual memory abilities, and study them in depth.

Question

8.6

What could we learn from these participant choices?

One person or a small group of people who have won the United States Memory Championship You would need to study individuals who have relatively normal memory abilities. By only studying a person or people with exceptional memory, you would not be able to generalize your findings to the larger population.

One person or a small group of people who have average memory abilities You were correct to recruit one or more individuals who have average memory abilities. HOWEVER, we would need to study large groups of people in order to generalize the findings to the larger population.

One person or a small group of people who have extremely poor memory abilities You would need to study individuals who have relatively normal memory abilities. By only studying a person or people with poor memory abilities, you would not be able to generalize your findings to the larger population.

One person or a small group of people who have a family history of memory loss Knowing whether people have a family history of memory loss does not give you the information you need. To know whether our memory is accurate, you need to know something about the memory abilities of the actual participants you recruit.

Trying to choose a sample of participants helps us realize that the CASE STUDY IS NOT THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN to test this question. We’d get more helpful results by studying large groups of people who have average memory abilities. We would also want to measure memory using established tests. This would help us determine whether our memory is accurate.

Click “Next” to go back and try again to select the most effective research design.

8.7

You have chosen Correlational design, which means you want to study the association between two or more variables. For example, when testing whether interest in school relates to time spent studying, researchers will measure individuals’ interest in school and how much time they spend studying. This allows researchers to determine whether being interested in school predicts more studying. (It does!)

Question

EmYJvTZJmqvV+5jm5N9Sn1KLQBhG+pBOvjr7Owqx6ePjDJYrT+VBan7kV6T0ipPUbukKbd6RL0o08fisyOuWDGERO9KsfL51OvwhN77Y6PveerPneX4ZkbhsKm0e3N5JiiDCaLBSkmM0hSUUvFK6QtJ/PB+ItdtM10vM3OKHM5pWyTvDnorHvfUOoapMSg3w58+QAJVp4bQGS8q74lVg1VuoQBXFAaRm8.8

To use the Correlational design, we could examine the association between how well people felt they memorized information and their actual performance when they tried to recall the information. But we would not know about what causes people to have accurate and inaccurate memories.We should always try to determine causality if at all possible when doing psychological research. In this case, that means we would need to determine whether presenting people with some information, compared with presenting others different information, causes people to have more or less accurate memories.

So, CORRELATIONAL IS NOT THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN for this study. We’d get more helpful results by studying large groups of people who have average memory abilities, and by comparing a group of participants who are presented certain pieces of information to memorize, with a group where the participants are not presented such information.

Click “Next” to go back and try again to select the most effective research design.

8.9

Nice work! You have correctly chosen to use an Experimental design for your study.

Next, you need to choose the most appropriate study participants.

Question

pl5eNjeM1xBLyGuvTTdTgrVdUV0RbKoBEC13RvzXmOSO/n405fjqwTSzCJayUGSj3IiNaq+Mhd5MtcAizBrYrB3TFjBajGSxYcwbVAR9QB5MenZHeTmbVab4xCQbfPcJZUlvXWpy16vT1OOOKKJqItNBHixt4c6c9I1WAfISj/uJoyfjAqptG0oYbeQ+hCF7HtIQkUHjK2TtenudjHSJEGoAHFB2Mo74+npIzJT2ZkcaePYUsBBk0lL2j9yOzAdhwsTQeBuHLb9pHUFj9Pa1/fD0u3CLGIdaHkhPdsfCL9JkHLh3Y9YAm4jPodJ6eV2uSzyzQVlyTAKBdC/WiavGibW5Lye0buZKfvty8vP4S+vlPp6oIF/qyEDpJ0JulQQLhCbf8kuxyCxXSXGxvUiNmIEmgyj8LfEKZ6z0ydF0Z3DpNsn0zx739UGy3PCCdSnR8OIUW+R7z8oQjUXV4y3oleDqdDhBNKbMaQOrWFGA8GBe5fWbOl63ED8uRFlU47aSAJOTCX6gI/esU1M+c0Glm9AL22WrVuu2jIyObQ==8.10

You chose A group of people who have won the United States Memory Championship, but this is NOT CORRECT.

This group is not the best choice. You would need to study individuals who have relatively normal memory abilities. By only studying people with exceptional memory, you would not be able to generalize your findings to the larger population.

Click “Next” to try again to choose the most appropriate study participants.

8.11

You chose A group of people who have extremely poor memory abilities, but this is NOT CORRECT.

This group is not the best choice. You would need to study individuals who have relatively normal memory abilities. By only studying people with poor memory abilities, you would not be able to generalize your findings to the larger population.

Click “Next” to try again to choose the most appropriate study participants.

8.12

You chose A group of people who have a family history of memory loss, but this is NOT CORRECT.

Knowing whether people have a family history of memory loss does not give you the information you need. To know whether our memory is accurate, you need to know something about the memory abilities of the actual participants you recruit.

Click “Next” to try again to choose the most appropriate study participants.

8.13

Good job! You have correctly chosen to use an Experimental design, which means you will be setting up an experimental condition and a control condition. You also chose an appropriate sample of participants—A group of people who have average memory abilities.

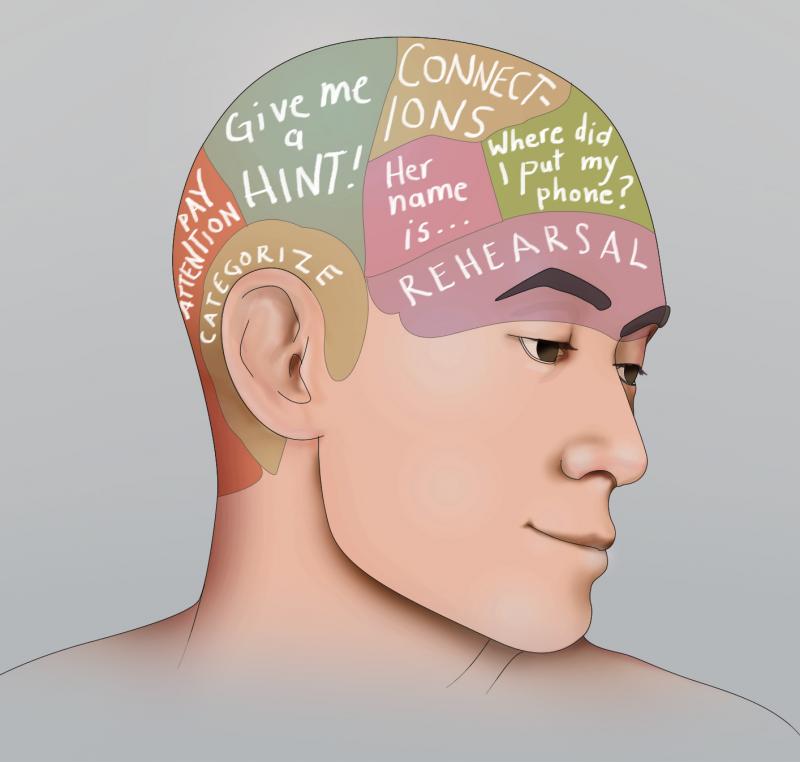

Now you need to determine how best to MEASURE the relevant behavior or mental process, which in this case is memory.

Let’s first try a demonstration of your own memory that may help you to better understand an appropriate measurement technique.

8.14

8.15

You got X out of 8 correct.

Here are the correct answers:

These are the words you DID see in your earlier list:

- pants

- shoes

- vests

These are the words you DID NOT see in your earlier list:

- yellow

- sun

- ties

- green

- socks

Did your memory fool you into thinking that “ties” or “socks” were on the earlier list? Many people believe they saw “ties” or “socks” on the earlier list, because those words fit into the same category of types of clothing. But in fact neither “ties” nor “socks” were on that earlier list. Our minds create these false memories more often than we’d like to believe!

Now that you’ve completed a simple test of your own memory, you should be prepared to consider the best way to MEASURE your participants’ memory.

8.16

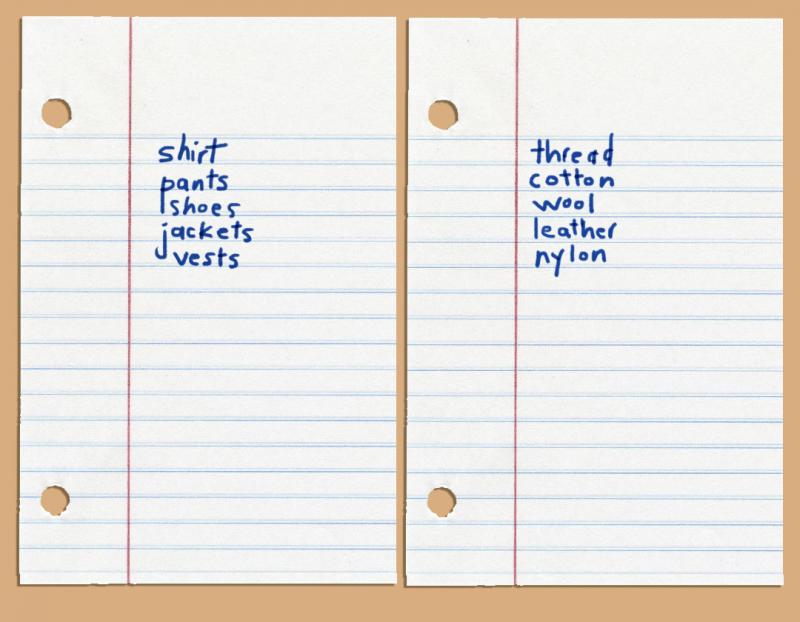

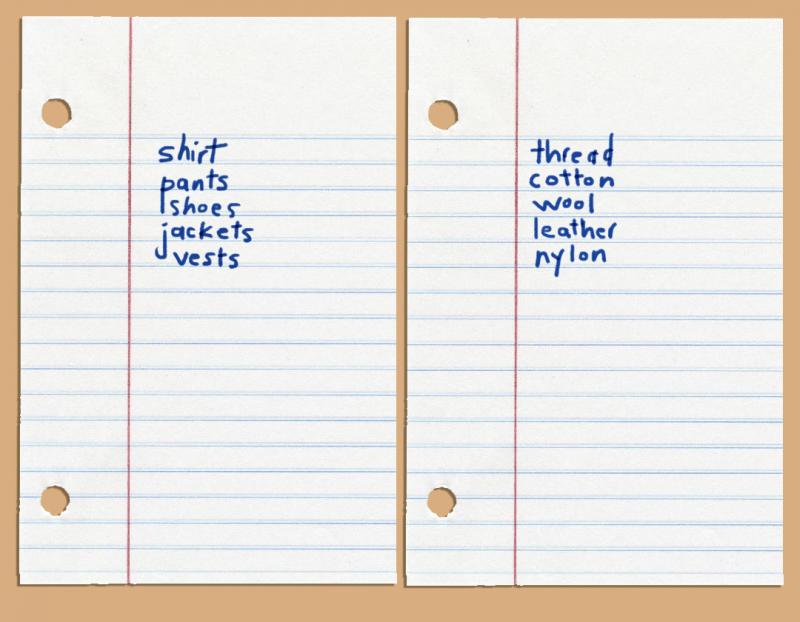

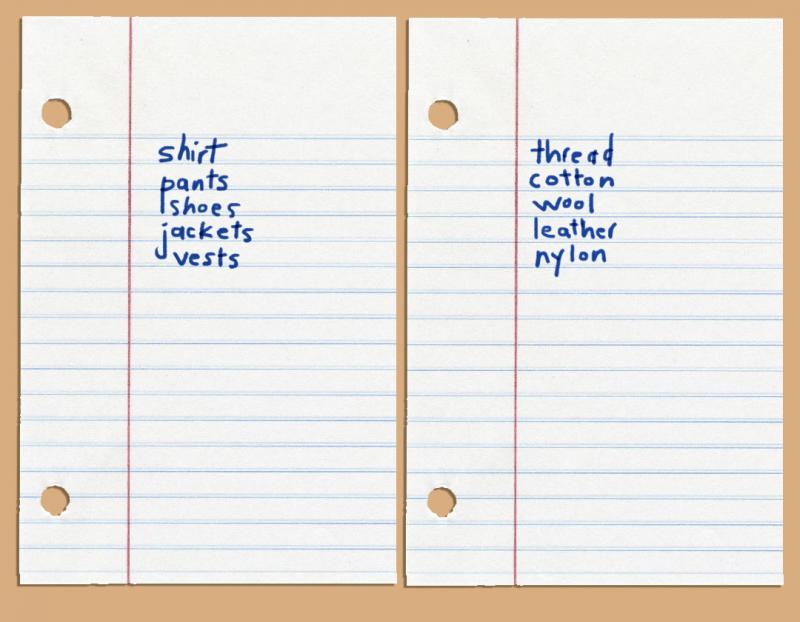

As we noted earlier, you chose to use an Experimental design. For the purposes of your study, let’s say you will set up your study similar to the memory self-test you just completed. You will have some participants (experimental group) try to memorize words related to a specific topic (types of clothing), whereas others (control group) will try to memorize words related to another topic (clothing material). In your study, the experimental group will see the words related to types of clothing: shirt, pants, shoes, jackets, and vests. The control group will see the words related to clothing material: thread, cotton, wool, leather, and nylon.

Question

NFkSQmnFfucmiHEUJm3stRnXFNKaWs1Q2OQ2JTLPvG9QQMxASwV7Ri0/O0FlEnSObcJIAuJjpSf8ApbJYanCUbT3otU3ABBV/1P18mcRmpLkFuP+qpTZy5QuxsncyNGruUUDE6MSzsMlbVYtCSAskd76teRIFug6i/kBOs+RWj5slsdndOtFDvMIQ9zyE7LCC2aJvtEzXHVb88ewoEFY4ttRQc/u6t6LErKbrpnzCnqJs96g8.17

You correctly chose to use an Experimental design, in which you had some participants (experimental group) try to memorize words related to a specific topic, whereas others (control group) tried to memorize words related to another topic. In your study, the experimental group saw words related to types of clothing: shirt, pants, shoes, jackets, and vests. The control group saw words related to clothing material: thread, cotton, wool, leather, and nylon.

You chose an appropriate sample of participants—a group of people who have average memory abilities. You also determined a good way to MEASURE the relevant behavior or mental process, memory. You measured participants’ level of certainty about whether they had seen certain words that fit with the topic of the list they had seen, but were not actually on that list. You learned from your own memory self-test that people sometimes have false memories. They remember the gist of words they saw more easily than the actual words.

8.18

Several actual studies have examined memory accuracy and whether people have false memories. These studies were similar to yours—participants first read lists of words, and later were tested on lists that contained words they did and did not see (Roediger & McDermott, 1995). The results are clear: People often have false memories. They remember seeing words that they didn’t see! In your study, the experimental group’s word list was designed to create a false memory for the words ties and socks. Because experimental participants saw words related to types of clothing (i.e., shirt, pants, shoes, jackets, and vests), they were more likely than control participants to incorrectly recall seeing the words ties and socks.

Knowing this, you need to consider how you can apply what you’ve learned to the larger population—beyond the people you’ve studied. Consider where you might encounter roadblocks to confidence in your results. What factors might keep you from being able to apply what you’ve learned in a broader context?

8.19

You tested whether our memory is accurate in two ways. First, you measured how well participants recalled the words they saw. Second, you measured whether seeing words related to types of clothing caused experimental participants to have a false memory more often than control participants. There are many factors that could affect memory. For example, have you noticed that some people enjoy memory games, whereas others do their best to avoid them? Factors that could interfere with your INTERPRETATION of results are called confounding variables.

Question

Select all of the factors that could affect your confidence about whether your participants’ memory is accurate (based on the ability to recall word lists):

ZycNTMvpRoSnXPUZl8FiVl5s+iDEL2Bo Fluency in English

3jskoxIwaHnoYr4Fsi2l/v3etGMIufia Damage to brain regions that do not influence memory

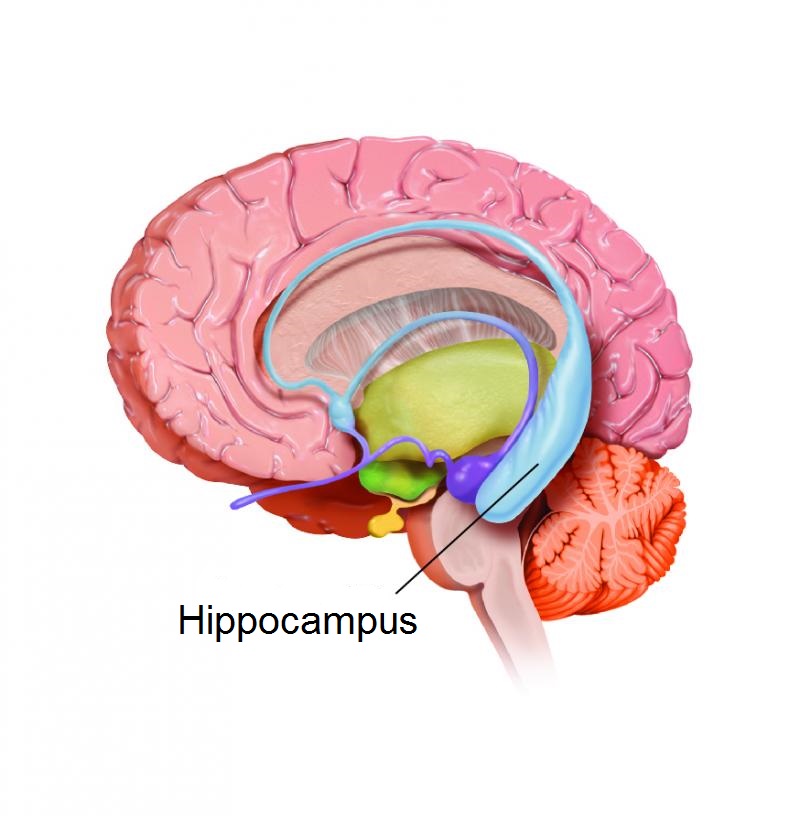

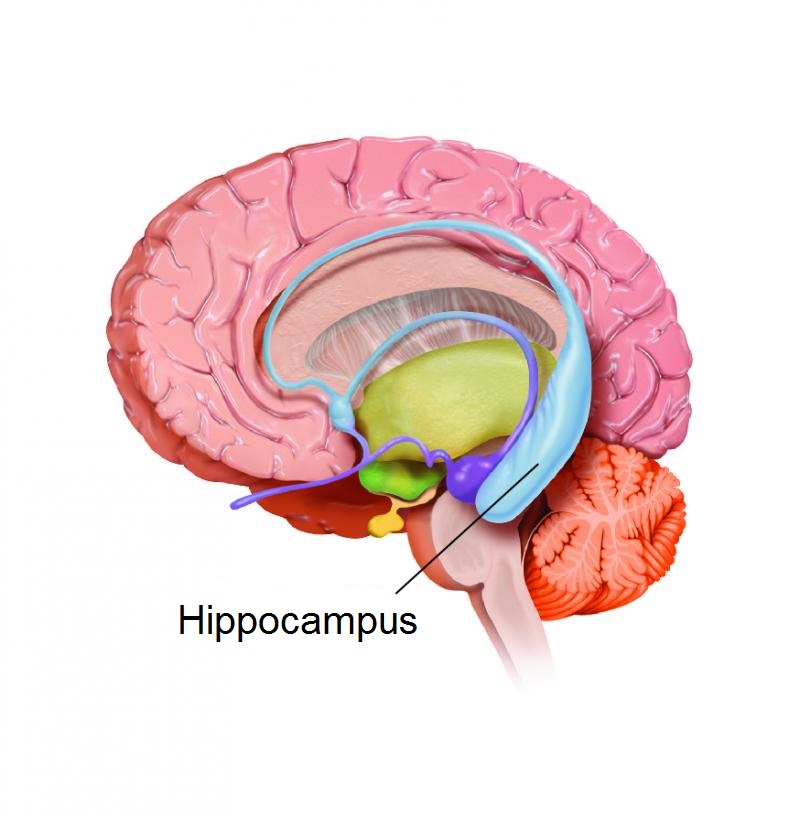

ZycNTMvpRoSnXPUZl8FiVl5s+iDEL2Bo Damage to the hippocampus, which is a brain region that aids memory

ZycNTMvpRoSnXPUZl8FiVl5s+iDEL2Bo An ability to accurately remember the days of the week for any date in the past 500 years

3jskoxIwaHnoYr4Fsi2l/v3etGMIufia Whether people enjoy reading about those with photographic memories

3jskoxIwaHnoYr4Fsi2l/v3etGMIufia Whether participants rely on public transportation for their everyday travel

Click on "Video Hint" below to see a brief animation describing Confounding Variables.

Video Hint

8.21

The confounding variables for your study would include those highlighted below:

You need to make sure that you only select research participants who are fluent in English. If participants can’t understand the words they see, they will have difficulty remembering them.

Participants with hippocampus damage might not be able to recall any words you show them, and such participants would not be representative of the larger population.

In order to apply your results to the general population, it is a good idea to only include people in your study who have average memory abilities.

Those with brain damage that does not affect memory centers should be able to participate in your study without disrupting the results. Other factors, such as whether participants like reading about those with superior memories or whether they regularly use public transportation, should not influence how well people remember word lists.

Note that by randomly assigning participants to either the experimental or control condition, you control for many other possible confounding variables. With random assignment, each participant has the same chance of being assigned to each group. This should give each of your groups a balanced number of participants expressing these variations.

Click on "Video Hint" below to see a brief animation describing Random Assignment.

Video Hint

8.23

You may do better on the Quiz if you take notes while watching this video. Feel free to pause the video or re-watch it as often as you like.

REFERENCES

Howe, M. L. (2008). Visual distinctiveness and the development of children’s false memories. Child Development, 79(1), 65-79.

Patihis, L., et al. (2013). False memories in highly superior autobiographical memory individuals. Proceedings of the National Academy on Science USA, 110, 20947-20952.

Roediger, H. L., III, & McDermott, K. B. (1995). Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21, 803-814.

8.24

QUIZ: NOW WHAT DO YOU KNOW?