10.14

Are Humans Necessary?

Margaret Atwood

Born in 1939, Margaret Atwood is a Canadian novelist, poet, and political activist. Although she generally does not think of herself as a science fiction writer, preferring to describe her writing as “speculative fiction,” Atwood sets a number of her works in the future, including the dystopian The Handmaid’s Tale, which is probably her most famous novel. Atwood is also the inventor of the LongPen, a videoconferencing system that allows authors to sign fans’ books remotely through the use of a robotic arm holding a pen.

KEY CONTEXT In this piece, published in 2014 in the New York Times, Atwood responds to the European Union’s decision in 2014 to commit $4 billion to robot innovation, and as she imagines what our future will be like as result, she traces how “humankind has been imagining nonbiological but sentient entities that do our bidding” for a long time.

Turning Point: European Union launches the world’s largest civilian robotics program.

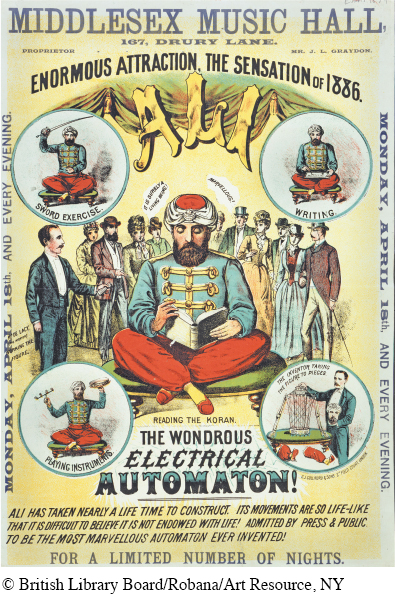

This 1887 advertisement is for Ali the Electrical Automaton. The illustrations show Ali reading the Koran, writing, playing instruments, and performing a sword exercise. Also shown is Mr. De Lacy, the inventor, operating the figure and taking it apart.

Welcome to The Future, one of our favorite playgrounds. We love dabbling about in it, as our numerous utopias and dystopias testify; like the Afterlife, it’s up for grabs, since no one has actually been there.

What fate is in store for us in The Future? Will it be a Yikes or a Hurrah? Zombie apocalypse? No more fish? Vertical urban farming? Burnout? Genetically modified humans? Will we, using our great-

Many of our proposed futures contain robots. The present also contains robots, but The Future is said to contain a lot more of them. Is that good or bad? We haven’t made up our minds. And while we’re at it, how about a robotic mind that can be made up more easily than a human one?

Sci-

5 Why do we dream up such things? Because, deep down, we desire them. Our species never puts much effort into things that aren’t on our own wish list. If we were technologically capable mice, we’d be perfecting deadly cat harpoons, or bird-

To understand Homo sapiens’ primary wish list, go back to mythology. We endowed the gods with the abilities we wished we had ourselves: immortality and eternal youth, flight, resplendent beauty, total power, climate control, ultimate weapons, delicious banquets minus the cooking and washing up — and artificial creatures at our beck and call.

In one of the oldest known texts, a Sumerian god makes two demons enter the world of Death to rescue a life-

As we moved closer to the modern age, we continued to amuse ourselves with tales of proto-

Once the modern age was upon us, we got serious about robots. The word “robot” was introduced in Karel Capek’s 1920 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), derived from a root meaning “slave” or “servitude.” In this, Capek was merely echoing Aristotle, who speculated long ago that people might be able to eliminate the miseries of slavery by creating devices that could move around by themselves, like Hephaestus’ metal tables, and do the heavy lifting for us. Capek’s robots, then, were devised as artificial slaves, thus doing away with the unfortunate need for real ones.

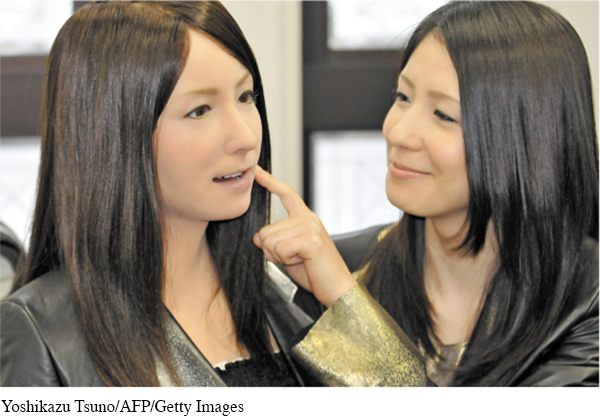

10 There’s nothing that spooks us more, say those who study such things, than beings that appear to be human but aren’t quite.

Or, as a story from the golden age of sci-

Uh-

And thereby hangs many a popular tale; for although we’ve pined for them and designed them, we’ve never felt down-

The worry seems to be that perfected robots, instead of being proud to serve their creators, will rebel, resisting their subservient status and eliminating or enslaving us. Like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice or the makers of golems, we can work wonders, but we fear that we can’t control the results. The robots in R.U.R. ultimately triumph, and this meme has been elaborated upon in story after story, both written and filmed, in the decades since.

15 A clever variant was supplied by John Wyndham in his 1954 story “Compassion Circuit,” in which empathetic robots, designed to react in a caring way to human suffering, cut off a sick woman’s head and attach it to a robot body. At the time Wyndham was writing, this plot line was viewed with some horror, but today we would probably say, “Awesome idea!” We’re already accustomed to the prospect of our future cyborgization, because — as Marshall McLuhan noted with respect to media — what we project changes us, what we farm also farms us, and thus what we roboticize may, in the future, roboticize us.

Maybe. Up to a point. If we let it.

Although I grew up in the golden age of sci-

These are benign uses of robotics, and there are many more examples. Manufacturing now employs robots heavily, loving their advantages: They never get tired, or need pension plans, or go on strike. This trend is causing a certain amount of angst: What will happen to the consumer base if robots replace all the human workers? Who will buy all the stuff the robots can so endlessly and cheaply churn out? Even seemingly nonthreatening uses of robots can have their hidden downsides.

But, their promoters say, think of the potential for saving lives! Nanorobots could revolutionize noninvasive surgery. And robots can already be deployed in environments that are hazardous for humans, such as bomb detonation and undersea exploration. These things are surely good.

Scientists use the term the “Uncanny Valley” to describe the discomfort that humans reportedly feel as they encounter robots or animated characters that are nearly lifelike.

20 We do, however, always push the envelope; it’s part of our great-

But it’s not all a one-

Back in our increasingly fiction-

You may soon be able to avail yourself of a remote kissing device that transmits the sensation of your sweetie’s kiss to your lips via haptic feedback and an apparatus that resembles a Silly Putty egg. (Just close your eyes.) [. . .]

Will remote sex on demand change human relationships? Will it change human nature? What is human nature, anyway? That’s one of the questions our robots — both real and fictional — have always prompted us to think about.

25 Every technology we develop is an extension of one of our own senses or capabilities. It has always been that way. The spear and the arrow extended the arm, the telescope extended the eye, and now the Kissinger kissing device extends the mouth. Every technology we’ve ever made has also altered the way we live. So how different will our lives be if the future we choose is the one with all these robots in it?

More to the point, how will we power that future? Every modern robotic form that exists, and every one still to come, depends on a supply of cheap energy. If the energy disappears, so will the robots. And, to a large degree, so will we, since the lifestyle we have built and come to depend on floats on a sea of electricity. Hephaestus’ bronze giant was powered by the ichor of the divine gods; we can’t use that, but we need to think up another energy source that’s both widely available and won’t end up killing us.

If we can’t do that, the number of possible futures available to us will shrink dramatically to one. It won’t be the Hurrah; it will be the Yikes. This will perhaps be followed — as in a Ray Bradbury story — by a chorus of battery-

Understanding and Interpreting

Margaret Atwood says that the reason we tell so many stories about robots is that “deep down, we desire them” (par. 5). Explain what she means by this.

What is in common among many of the stories of robots that Atwood includes?

In paragraph 9, Atwood tells the reader that the original meaning of the word robot is derived from the words meaning “slave” or “servitude.” How is this underlying meaning revealed in our stories of robots, as summarized by Atwood?

Explain what Atwood means when she paraphrases what “Marshall McLuhan noted with respect to media—

what we project changes us, what we farm also farms us, and thus what we roboticize may, in the future, roboticize us” (par. 15). In several places in this piece, especially paragraphs 20 and 21, Atwood makes reference to gender relations and robots. What, if any, difference does she note between the ways that men and women view robots?

In some ways, this article is a series of seemingly random musings on robots. What is one unifying idea that Atwood presents about humans and robots in this piece?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Reread paragraphs 1–

3 and analyze how Atwood’s language choices reflect her tone toward the future. In paragraph 17, Atwood mentions her own personal experiences with robots. What is the purpose of this section and how does it help to illustrate her ideas about robots?

Read the final two paragraphs of this article. What is Atwood’s tone toward the future here? How is it similar to or different from the tone at the beginning of the piece?

There are several places where Atwood attempts to lighten the mood of the piece through humor. Identify one section where Atwood pokes fun at humans’ interest in robots, and explain how she creates the humor.

One claim Atwood makes in this piece is “We do, however, always push the envelope” (par. 20). What evidence does she include to support this claim?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

In paragraph 18, Atwood describes the effect that robots might have on manufacturing and consumerism. Write an argument that makes and supports a claim about the likely economic effect robots will have in the future.

Do you think the robotic future will be “Hurrah” or “Yikes” or something else? Why?

Think about a film or story you know that contains robots. How does the representation of robots in that text compare to what Atwood describes in this piece? How do the robots in that text reflect some aspect of humanity?