10.1 CENTRAL TEXT

from A Small Place

Jamaica Kincaid

Elaine Potter Richardson, who later changed her name to Jamaica Kincaid, was born in 1949 on the Caribbean island of Antigua, then a British colony. She came to the United States as a teenager to work as an au pair in New York City, where she then attended the New School for Social Research. Kincaid became a staff writer for the New Yorker in 1975 and published much of her short work there. Perhaps her most widely known works are “Girl” from At the Bottom of the River, a collection of short stories (1985), and Annie John (1985), a novel. Her most recent work is the novel See Now Then (2013).

KEY CONTEXT A Small Place, published in 1988, is an extended essay about Antigua. The first person expatriate narrator takes the reader, an imagined tourist, on a journey through both Antigua of the present time and the colonial past. A Small Place can be described as a postcolonial text, which means that it addresses how a colonialized group both adopts and resists the culture and values of the colonizing power. The following selection is the opening chapter of A Small Place.

The history of Antigua, located southeast of Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Sea, can be dated to nearly 2000 B.C. with settlements of Siboney (Arawak for “stone people”), who were eventually replaced by Arawaks and Island Caribs between 1200 and 1500 C.E. The indigenous peoples’ earliest recorded contact with Europeans was with Christopher Columbus on his second voyage in 1493. He named the island Santa Maria de la Antigua after the patron saint of the Spanish city of Seville. In 1632, the British succeeded in colonizing the island, but it was not until 1684, with the arrival of Christopher Codrington, that a profitable sugar plantation industry was established. African slaves were brought to the island to work on these plantations. By the end of the eighteenth century, Antigua had become a strategic port and valuable commercial colony. In 1834, when Britain abolished slavery in the Caribbean, Antigua became the first of the colonies to emancipate its slaves. The island remained British, however, until its independence in 1981, and Antigua retains membership in the British Commonwealth.

If you go to Antigua as a tourist, this is what you will see. If you come by aeroplane, you will land at the V. C. Bird International Airport. Vere Cornwall (V. C.) Bird is the Prime Minister of Antigua. You may be the sort of tourist who would wonder why a Prime Minister would want an airport named after him — why not a school, why not a hospital, why not some great public monument? You are a tourist and you have not yet seen a school in Antigua, you have not yet seen the hospital in Antigua, you have not yet seen a public monument in Antigua. As your plane descends to land, you might say, What a beautiful island Antigua is — more beautiful than any of the other islands you have seen, and they were very beautiful, in their way, but they were much too green, much too lush with vegetation, which indicated to you, the tourist, that they got quite a bit of rainfall, and rain is the very thing that you, just now, do not want, for you are thinking of the hard and cold and dark and long days you spent working in North America (or, worse, Europe), earning some money so that you could stay in this place (Antigua) where the sun always shines and where the climate is deliciously hot and dry for the four to ten days you are going to be staying there; and since you are on your holiday, since you are a tourist, the thought of what it might be like for someone who had to live day in, day out in a place that suffers constantly from drought, and so has to watch carefully every drop of fresh water used (while at the same time surrounded by a sea and an ocean — the Caribbean Sea on one side, the Atlantic Ocean on the other), must never cross your mind.

You disembark from your plane. You go through customs. Since you are a tourist, a North American or European — to be frank, white —and not an Antiguan black returning to Antigua from Europe or North America with cardboard boxes of much needed cheap clothes and food for relatives, you move through customs swiftly, you move through customs with ease. Your bags are not searched. You emerge from customs into the hot, clean air: immediately you feel cleansed, immediately you feel blessed (which is to say special); you feel free. You see a man, a taxi driver; you ask him to take you to your destination; he quotes you a price. You immediately think that the price is in the local currency, for you are a tourist and you are familiar with these things (rates of exchange) and you feel even more free, for things seem so cheap, but then your driver ends by saying, “In U.S. currency.” You may say, “Hmmmm, do you have a formal sheet that lists official prices and destinations?” Your driver obeys the law and shows you the sheet, and he apologises for the incredible mistake he has made in quoting you a price off the top of his head which is so vastly different (favouring him) from the one listed. You are driven to your hotel by this taxi driver in his taxi, a brand-

It’s a good thing that you brought your own books with you, for you couldn’t just go to the library and borrow some. Antigua used to have a splendid library, but in The Earthquake (everyone talks about it that way — The Earthquake; we Antiguans, for I am one, have a great sense of things, and the more meaningful the thing, the more meaningless we make it) the library building was damaged. This was in 1974, and soon after that a sign was placed on the front of the building saying, THIS BUILDING WAS DAMAGED IN THE EARTHQUAKE OF 1974. REPAIRS ARE PENDING. The sign hangs there, and hangs there more than a decade later, with its unfulfilled promise of repair, and you might see this as a sort of quaintness on the part of these islanders, these people descended from slaves —what a strange, unusual perception of time they have, REPAIRS ARE PENDING, and here it is many years later, but perhaps in a world that is twelve miles long and nine miles wide (the size of Antigua) twelve years and twelve minutes and twelve days are all the same. The library is one of those splendid old buildings from colonial times, and the sign telling of the repairs is a splendid old sign from colonial times. Not very long after The Earthquake Antigua got its independence from Britain, making Antigua a state in its own right, and Antiguans are so proud of this that each year, to mark the day, they go to church and thank God, a British God, for this. But you should not think of the confusion that must lie in all that and you must not think of the damaged library. You have brought your own books with you, and among them is one of those new books about economic history, one of those books explaining how the West (meaning Europe and North America after its conquest and settlement by Europeans) got rich: the West got rich not from the free (free — in this case meaning got-

seeing connections

Following is the opening paragraph from a 2014 article in a magazine for upscale travelers. Compare and contrast the speaker’s perceptions with those of the narrator in the opening to A Small Place, focusing specifically on the speakers’ tones.

“Let me take you into the sun,” said Louvaine, our Hermitage Bay liaison at the airport. No sooner had she spotted our pale winter faces at baggage claim than she swept our ten-

Oh, but by now you are tired of all this looking, and you want to reach your destination — your hotel, your room. You long to refresh yourself; you long to eat some nice lobster, some nice local food. You take a bath, you brush your teeth. You get dressed again; as you get dressed, you look out the window. That water — have you ever seen anything like it? Far out, to the horizon, the colour of the water is navy-

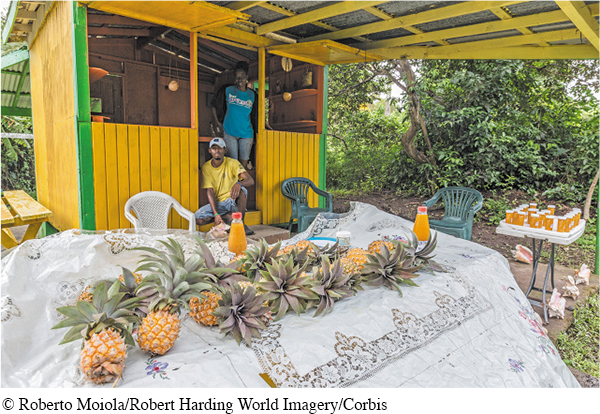

How might a tourist see this scene from contemporary Antigua, and how might Kincaid see it? Write a brief description from the perspective of each.

5 The thing you have always suspected about yourself the minute you become a tourist is true: A tourist is an ugly human being. You are not an ugly person all the time; you are not an ugly person ordinarily; you are not an ugly person day to day. From day to day, you are a nice person. From day to day, all the people who are supposed to love you on the whole do. From day to day, as you walk down a busy street in the large and modern and prosperous city in which you work and live, dismayed, puzzled (a cliché, but only a cliché can explain you) at how alone you feel in this crowd, how awful it is to go unnoticed, how awful it is to go unloved, even as you are surrounded by more people than you could possibly get to know in a lifetime that lasted for millennia, and then out of the corner of your eye you see someone looking at you and absolute pleasure is written all over that person’s face, and then you realise that you are not as revolting a presence as you think you are (for that look just told you so). And so, ordinarily, you are a nice person, an attractive person, a person capable of drawing to yourself the affection of other people (people just like you), a person at home in your own skin (sort of; I mean, in a way; I mean, your dismay and puzzlement are natural to you, because people like you just seem to be like that, and so many of the things people like you find admirable about yourselves — the things you think about, the things you think really define you — seem rooted in these feelings): a person at home in your own house (and all its nice house things), with its nice back yard (and its nice back-

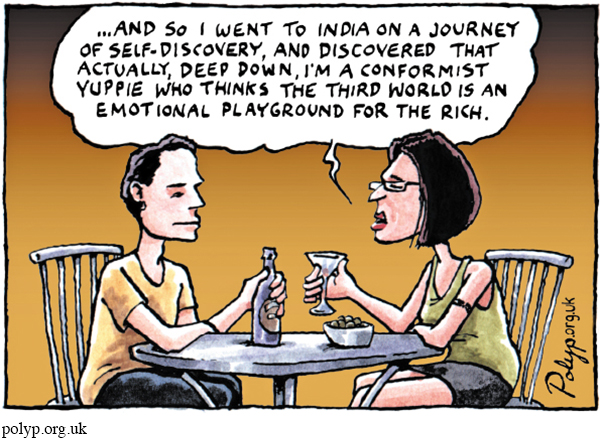

In what ways does this cartoon sum up Kincaid’s view as expressed in “A Small Place”? What is the effect of hearing this sentiment expressed as a self-

That the native does not like the tourist is not hard to explain. For every native of every place is a potential tourist, and every tourist is a native of somewhere. Every native everywhere lives a life of overwhelming and crushing banality and boredom and desperation and depression, and every deed, good and bad, is an attempt to forget this. Every native would like to find a way out, every native would like a rest, every native would like a tour. But some natives — most natives in the world — cannot go anywhere. They are too poor. They are too poor to go anywhere. They are too poor to escape the reality of their lives; and they are too poor to live properly in the place where they live, which is the very place you, the tourist, want to go — so when the natives see you, the tourist, they envy you, they envy your ability to leave your own banality and boredom, they envy your ability to turn their own banality and boredom into a source of pleasure for yourself.

Understanding and Interpreting

In the long opening paragraph, what assumptions does Jamaica Kincaid make in order to characterize “a tourist”? What characteristics does she ascribe to tourists in general?

What do you think Kincaid means when she states that the tourist emerging from customs “feel[s] free” (par. 2)?

What points is Kincaid making about the economic situation in Antigua by focusing on the cars, drivers, and conditions of the roads?

Why is the library particularly significant to Kincaid (par. 3)?

What is Kincaid’s purpose in pointing out the drug smuggler and the “young and beautiful” woman named Evita (par. 3)?

To what extent do you trust Kincaid’s reliability as a narrator? Is she being objective? Cite specific passages to support your response.

Kincaid describes how someone who is “ordinarily [. . .] a nice person, an attractive person” “become[s] a tourist,” who is, by Kincaid’s definition, “an ugly human being” (par. 5). What forces are at work in this process of change? Why doesn’t the would-

be tourist resist the change, according to Kincaid? What is the “banality and boredom” (par. 6) that Kincaid describes in the life of both the native and tourist? To what extent do you agree with her analysis?

Kincaid identifies many qualities that distinguish Antiguans from the tourists. Choose one of them, explain the differences, and analyze how this distinction assists Kincaid in her argument.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

One of the most outstanding features of Kincaid’s style in this piece is her ironic use of the second person pronoun “you” to address her readers. What effect does she achieve in the first paragraph alone? How would writing in third person change the effect? (For example, “When people come to Antigua as tourists, this is what they will see. If they come by aeroplane, they will land . . .”)

Which descriptions do you find particularly harsh? Cite specific examples to support your response. Why do you think Kincaid includes such strong language? (Keep in mind that a reader can simply stop reading at any time, and Kincaid is no doubt aware of this fact.)

Select a paragraph or two and focus on Kincaid’s use of parenthetical comments. What is her purpose in using so many asides? In what ways do these sections represent a shift in voice? (You might try reading the section without the parentheticals to consider the impact.)

What is the effect of Kincaid’s use of repetition as a rhetorical strategy? How does she avoid (or does she fail to avoid) making the repetition of the same word or phrase monotonous?

If you were unaware of Kincaid’s background, at what point in the essay would you realize that it is being narrated by someone who is originally from Antigua? How does that awareness affect your attitude toward the narrator?

Kincaid suggests that the tourist does not know if ground-

up glass is “really a [local] delicacy” (par. 5) or if the fish being served at dinner is, in fact, deadly. Is she being serious at this point or sarcastic? Cite specific passages to support your view. How do you feel about Kincaid telling you what “you” as a tourist think? She also assumes that ”you” are white and Western and wealthy. To what extent does this seem presumptuous? Is it off-

putting, or effective as a rhetorical strategy? Is it stereotyping, an insightful method of inquiry, or something else? Explain your reaction. In the final paragraph of the excerpt, Kincaid refers more generally to “the native” and “the tourist.” In what ways does Kincaid’s attitude change from the rest of the piece? In what ways does this paragraph make you re-

evaluate any of the feelings you experienced as you read the preceding paragraphs?

Topics for Composing

Argument

Utopia or dystopia? In A Small Place, Jamaica Kincaid explores the same place from different perspectives. Based on this opening chapter, in what ways is it a utopian vision of an idyllic island paradise? In what ways are the political and economic realities dystopian?Research

This essay was written in 1988. Research the things that Kincaid describes and discuss whether they remain the same today. Is the library open? Is the sewer system developed? Then comment on how your research has informed your view on whether it is right or wrong to be a tourist in Antigua.Argument

What issues might you raise to challenge some of Kincaid’s assumptions or to question her beliefs in this piece? Respond to Kincaid by acknowledging her point and then refuting it by saying, “Yes _____________, but _____________.” What tone would you take to encourage her to listen?Argument

Would you go to Antigua or any similar country as a tourist? If you’ve been there before, would you go back? Answer that specific question in the broader context of whether it is ever “right” for someone from a wealthy, powerful country to visit poorer countries as a tourist. Are there ways to be a tourist that are different from the way that Kincaid describes in A Small Place? Does it matter, for example, if the tourist makes an effort to become aware of the country’s history and culture?Multimodal/Narrative

Kincaid opens her essay, “If you go to Antigua as a tourist, this is what you will see.” She then explores how our expectations determine what we actually see. Take that idea and apply it to your home, neighborhood, town, or city. Select a series of five or six still images, and then write a guide for an audience that you believe has preconceptions or misconceptions about the place. Consider starting out, “If you go to _____________ as a tourist, this is what you will see,” though you need not model your tone on Kincaid’s. Let the images guide your narrative.