Close Reading — The Basis of a Good Rhetorical Analysis

A good rhetorical analysis begins with close, careful reading. Like any analysis, a rhetorical analysis is a three-

Make observations.

Identify patterns.

Draw conclusions.

So, let’s start by figuring out what to look for when you are making observations about a writer or speaker’s use of rhetoric. For this Workshop, we’re going to work with “Free to Be Happy” by Jon Meacham (p. 892), an essay you may have read as part of the Conversation on the pursuit of happiness.

Make Observations

Establishing Context. One of the first things you want to make observations about is the context for the piece you are analyzing—

Of all the aspects of the rhetorical situation, the writer’s purpose is the most important to understand when preparing for a rhetorical analysis. Without understanding the speaker’s purpose, you can’t know if his or her rhetorical moves are working for the speaker, or against the speaker. In some cases, such as a timed writing, you may be given contextual information as part of your instructions or as background. If so, you should take note and start thinking about how that context affects the rhetoric of the text. Is the speaker a noted authority who has been invited to address a friendly audience? Is he or she an everyday citizen publishing a letter in response to a highly controversial community issue or election?

In situations in which you need to figure out the context on your own, you may need to do a little digging: Where was the piece published? What is the author’s background? In the case of Meacham’s essay, take into account that it appeared in Time, a weekly print and online newsmagazine, with a large audience of educated professionals. Of Time’s 25 million readers, 20 million are in the United States. Also consider that the article was one of several in a special issue on the topic of “The Pursuit of Happiness.” Moreover, Meacham is an executive editor at Random House publishing company and a contributing editor to Time. Perhaps most important, in terms of the context for this article, is that he has won many awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, for his history books. These include biographies of Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, and an analysis of the civil rights movement.

What does all of this information tell you? Most directly, it tells you that Meacham is a respected expert on U.S. history, so he brings authority to the writing. Particularly key to this essay is his expertise as a biographer of Thomas Jefferson.

ACTIVITY

Using the information above — and anything else about the publication or author that you discover through your own research — how would you characterize the relationship between this writer and his audience? What assumptions can we reliably make about the audience? What approach (or approaches) will likely appeal to the members of Meacham’s audience? What is Meacham’s ethos in this context?

Looking at the Text. Remember that in the Make Observations stage, you are just gathering information. So, read (or reread) the essay, noting ideas and language that stand out to you.

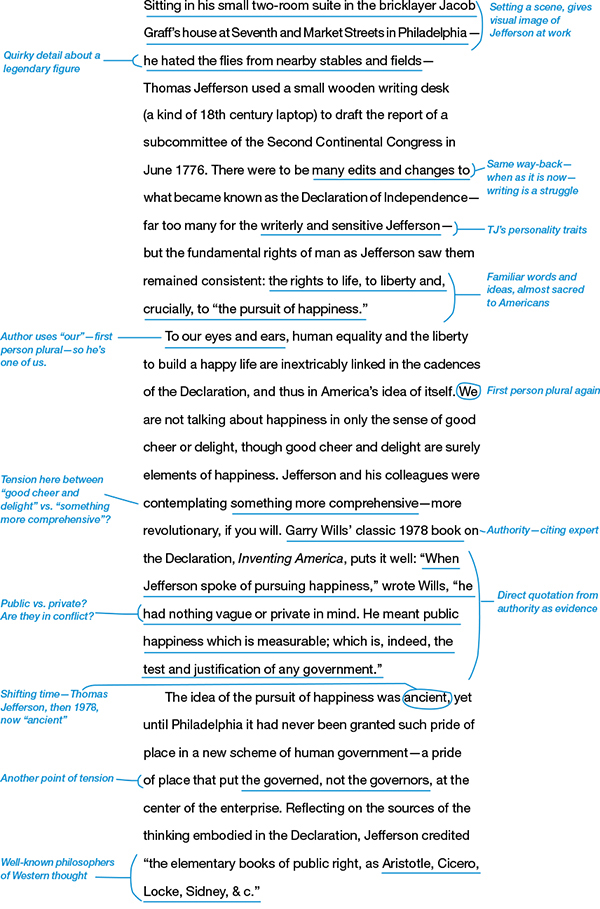

Let’s get into the text itself with a close reading of the opening three paragraphs. We’ll use annotations to mark what we see as we read through:

These observations, based as they are on only a few paragraphs, aren’t enough to determine exactly what Meacham’s purpose is, but we can see where he’s headed. He’s writing about the meaning of “the pursuit of happiness” today, but giving his readers a historical perspective on the idea by taking us back to 1776, and even beyond that to earlier thinkers who influenced the authors of the Declaration of Independence, including the Greek philosopher Aristotle.

Is his purpose to contrast today’s values and those of Jefferson and his colleagues?

Does Meacham see a tension between individual desires and what’s best for the community?

Making questions out of your observations is a good way to begin figuring out a writer’s purpose. These focus your reading while leading you to further exploration. At this early stage of analysis you don’t want to eliminate possible interpretations; you want to open up possibilities.

ACTIVITY

Go through the rest of Meacham’s essay (p. 892) and take note of the people, real or imagined, that Meacham refers to. Why might he include so many? Are they fairly similar or quite different? How are Meacham’s readers likely to respond to them? Develop at least three questions based on the persons alluded to or cited. (If you are unfamiliar with any of the allusions, such as “Rockwellian optimism,” for example, look them up.) What other questions can you generate based on the names you’ve noted?

Identify Patterns

Thus far, we have simply been making observations about the rhetorical context and what Meacham is doing as he builds his argument. The next step is to find a pattern or patterns with these observations.

If we look back at our observations, we see a series of notes about setting a scene and giving us quirky personal information about Jefferson. What pattern or patterns might link these observations—

We also have a series of notes about tensions that all seem to relate to defining happiness as either personal delight or public well-

Our notes also include the observation that Meacham writes in first person—

One way to organize your observations when you’re writing a rhetorical analysis is to work with the three rhetorical appeals: ethos, logos, and pathos. For each one of the appeals, you can look for specific strategies that show that appeal in action. Here’s an example.

Given the historical nature of the argument Meacham is making, logos is a natural place to start. Look back over those names you listed in the Activity above. You’ll notice that Meacham cites the contemporary scholar Garry Wills; another well-

Draw Conclusions

Once a pattern emerges, it’s time to draw conclusions. In the case of a rhetorical analysis, that means connecting the strategies you’ve discovered back to the author’s purpose.

Meacham appeals to a pretty well-

ACTIVITY

Identify and analyze at least two strategies that Meacham uses to appeal to pathos. How do these strategies help him achieve his purpose of emphasizing the public and communal nature of happiness? Consider Meacham’s overall (“big picture”) approaches, but also such elements of style as connotative language and allusions.