10.5

Nikki-

Nikki Giovanni

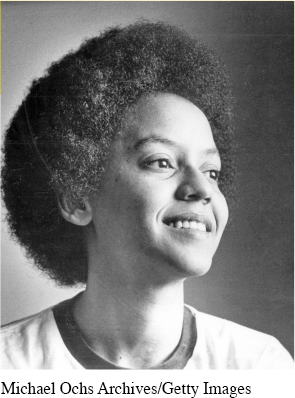

One of the most widely read American poets, Yolanda Cornelia “Nikki” Giovanni (b. 1943) is currently a University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, she graduated from Fisk University and went on to graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania. She has written more than a dozen volumes of poetry, three collections of essays, and many children’s books. Among her many awards and honors are three NAACP Image Awards, the Langston Hughes Medal for poetry, and the Rosa L. Parks Woman of Courage Award. This poem appeared in Black Feeling, Black Talk, Black Judgment (1968), a collection from early in her career.

KEY CONTEXT With the civil rights movement as a backdrop, much of the African American literature of the 1960s focused on the experience of those who overcame the difficult circumstances of racism, poverty, nontraditional family structures, and abuse. The emphasis was on sadness, struggle, and ultimate triumph over adversity. In this poem, Giovanni has a different take on how those outside these experiences might define “adversity.”

childhood remembrances are always a drag

if you’re Black

you always remember things like living in Woodlawn

with no inside toilet

5 and if you become famous or something

they never talk about how happy you were to have

your mother all to yourself and how good the water felt when you got your bath from one of those

big tubs that folk in chicago barbecue in

and somehow when you talk about home

10 it never gets across how much you

understood their feelings

as the whole family attended meetings about Hollydale1

and even though you remember

your biographers never understand

15 your father’s pain as he sells his stock

and another dream goes

And though you’re poor it isn’t poverty that

concerns you

and though they fought a lot

20 it isn’t your father’s drinking that makes any difference

but only that everybody is together and you

and your sister have happy birthdays and very good Christmases

and I really hope no white person ever has cause to write about me

because they never understand Black love is Black wealth and they’ll

25 probably talk about my hard childhood and never understand that

all the while I was quite happy

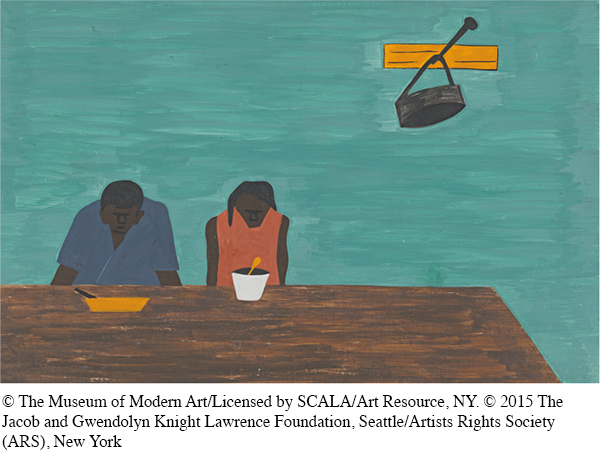

Jacob Lawrence, They were very poor (part of the Migration Series), 1941. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12˝ x 18˝. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Understanding and Interpreting

Brainstorm your responses to the phrase “hard childhood” (l. 25) or growing up “poor” (l. 17). How does this poem challenge those associations? Cite specific lines or phrases.

Who is the speaker? What visual image do you have of her? Why?

How do you interpret lines 17–

18: “And though you’re poor it isn’t poverty that / concerns you”? What is the speaker’s attitude toward her hypothetical biographers or any “white person [who] ever has cause to write about” her (l. 23)? How might that attitude affect how readers who are not African American react to this poem?

At the end of the poem, the speaker characterizes her childhood as “quite happy.” How does she define “happiness”?

Giovanni wrote this poem a few days after the funeral of Martin Luther King Jr. Does this fact influence your understanding of “Nikki-

Rosa,” and if so, how? If not, why not?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

How does the speaker, an adult looking back, convey the immediacy of her childhood experiences?

What is the effect of the absence of punctuation in the poem? Does it contribute to, reinforce, or distract from the ideas Giovanni is expressing?

Read the first few lines of the poem in two different ways: first, link lines 1 and 2; then, read it with the clause that is line 2 as part of the subsequent lines. What does Giovanni achieve with this deliberate ambiguity?

What difference does the qualifier “quite” make in the final line of the poem? What do you think Giovanni wanted to achieve by writing “quite happy” (l. 26) instead of simply “happy”?

Giovanni has explained that her poetry comes out of the African American oral tradition. What specific qualities in this poem reflect an oral tradition?

How would you describe the tone of this poem? Try using two words to capture the complexity, such as two adjectives (“angry but hopeful”) or an adverb and adjective (“sadly ironic”).

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

In many ways, “Nikki-

Rosa” is a poem of the 1960s, a time of the civil rights and Black Pride movements. After doing some research into these, discuss the extent to which you believe “Nikki- Rosa” both represents and transcends the specific time period in which Giovanni wrote it. Write either a narrative or a poem in the style of “Nikki-

Rosa” that centers on an experience you have had that others would assume is negative but that you see differently. Giovanni believes that poetry in the African American tradition cannot be separated from music. As a result, she has made albums of her poetry and performed with a New York religious choir. Set “Nikki-

Rosa” to music that you think provides an interpretive or fitting background; explain your choice in specific terms of the poem.