10.7

The Joy of Less

Pico Iyer

One of the most respected travel writers today, Pico Iyer (b. 1957) has described himself as “a global village on two legs.” He was born in Oxford, England, to Indian parents, and immigrated to the United States, where he lived in California. Iyer was educated at Oxford University and got his masters in literature from Harvard University. He currently lives much of each year in Japan. He is the author of numerous books on crossing cultures, including Video Night in Kathmandu (1989), The Lady and the Monk: Four Seasons in Kyoto (1992), The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home (2001), The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama (2009), and The Man within My Head (2013). An essayist for Time since 1986, Iyer also writes regularly for Harper’s, the New Yorker, and many other publications. The following essay appeared in the New York Times in 2009 as part of a series on “spiritual literacy.”

The beat of my heart has grown deeper, more active, and yet more peaceful, and it is as if I were all the time storing up inner riches . . . My [life] is one long sequence of inner miracles.” The young Dutchwoman Etty Hillesum wrote that in a Nazi transit camp in 1943, on her way to her death at Auschwitz two months later. Towards the end of his life, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “All I have seen teaches me to trust the creator for all I have not seen,” though by then he had already lost his father when he was 7, his first wife when she was 20 and his first son, aged 5. In Japan, the late 18th-

In the corporate world, I always knew there was some higher position I could attain, which meant that, like Zeno’s arrow,1 I was guaranteed never to arrive and always to remain dissatisfied.

I’m not sure I knew the details of all these lives when I was 29, but I did begin to guess that happiness lies less in our circumstances than in what we make of them, in every sense. “There is nothing either good or bad,” I had heard in high school, from Hamlet, “but thinking makes it so.” I had been lucky enough at that point to stumble into the life I might have dreamed of as a boy: a great job writing on world affairs for Time magazine, an apartment (officially at least) on Park Avenue, enough time and money to take vacations in Burma, Morocco, El Salvador. But every time I went to one of those places, I noticed that the people I met there, mired in difficulty and often warfare, seemed to have more energy and even optimism than the friends I’d grown up with in privileged, peaceful Santa Barbara, California, many of whom were on their fourth marriages and seeing a therapist every day. Though I knew that poverty certainly didn’t buy happiness, I wasn’t convinced that money did either.

So — as post-

5 I’m no Buddhist monk, and I can’t say I’m in love with renunciation in itself, or traveling an hour or more to print out an article I’ve written, or missing out on the N.B.A. Finals. But at some point, I decided that, for me at least, happiness arose out of all I didn’t want or need, not all I did. And it seemed quite useful to take a clear, hard look at what really led to peace of mind or absorption (the closest I’ve come to understanding happiness). Not having a car gives me volumes not to think or worry about, and makes walks around the neighborhood a daily adventure. Lacking a cell phone and high-

When the phone does ring — once a week — I’m thrilled, as I never was when the phone rang in my overcrowded office in Rockefeller Center. And when I return to the United States every three months or so and pick up a newspaper, I find I haven’t missed much at all. While I’ve been rereading P.G. Wodehouse, or Walden, the crazily accelerating roller-

seeing connections

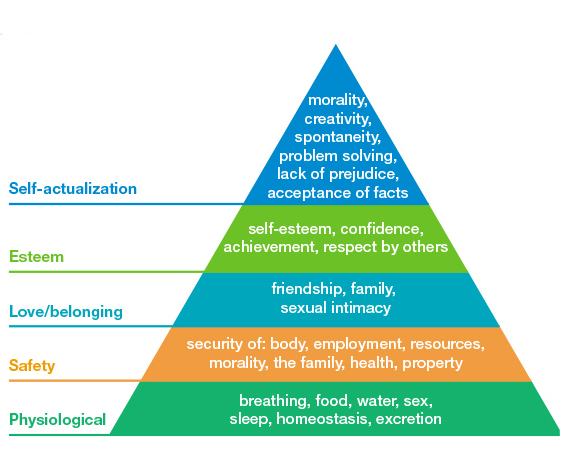

In 1943, American psychologist Abraham Maslow classified human needs into a hierarchy that moves from survival to self-

How does this idea compare with iyer’s thoughts in his essay?

Perhaps happiness, like peace or passion, comes most when it isn’t pursued.

I certainly wouldn’t recommend my life to most people — and my heart goes out to those who have recently been condemned to a simplicity they never needed or wanted. But I’m not sure how much outward details or accomplishments ever really make us happy deep down. The millionaires I know seem desperate to become multimillionaires, and spend more time with their lawyers and their bankers than with their friends (whose motivations they are no longer sure of). And I remember how, in the corporate world, I always knew there was some higher position I could attain, which meant that, like Zeno’s arrow, I was guaranteed never to arrive and always to remain dissatisfied.

Being self-

10 If you’re the kind of person who prefers freedom to security, who feels more comfortable in a small room than a large one and who finds that happiness comes from matching your wants to your needs, then running to stand still isn’t where your joy lies. In New York, a part of me was always somewhere else, thinking of what a simple life in Japan might be like. Now I’m there, I find that I almost never think of Rockefeller Center or Park Avenue at all.

Understanding and Interpreting

This essay was published less than a year after the Great Recession of 2008. How does that timing affect what Pico Iyer has to say and how readers are likely to respond?

What does Iyer mean in paragraph 6 by “[l]iving in the future tense”?

To what extent is Iyer suggesting that the setting of Japan, particularly the area around Kyoto, is more conducive to the life he has chosen than New York City or Santa Barbara, California?

In this essay, how does Iyer define “happiness”? Do you think the title is his definition?

Is this essay actually just another rant—

although in a gentle tone— against technology? Cite specific passages to support your response.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What is the effect of the references that Iyer makes in the opening paragraph? What point is he making with all three of these?

The readers of the New York Times are, generally, well educated, widely read, and interested in world events. How does Iyer appeal to such an audience? Cite specific passages and examples.

What is Iyer’s purpose? Is he trying to persuade his readers to follow his example? Is he simply relating his own experience? Something else?

Iyer advocates a simpler life in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau, a choice, one could argue, not available to everyone. What strategies does Iyer employ to avoid sounding smug or even elitist?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Choose one of the quotations below from Iyer, and write a brief essay supporting or challenging his statement. Be sure to draw on your own personal experience and knowledge as you explain your ideas. You may also choose another quotation from the piece, if you’d prefer.

“I’m not sure how much outward details or accomplishments ever really make us happy deep down” (par. 8).

“I always knew there was some higher position I could attain, which meant that, like Zeno’s arrow, I was guaranteed never to arrive and always to remain dissatisfied” (par. 8).

“And then it seems that happiness, like peace or passion, comes most freely when it isn’t pursued” (par. 9).

Although Iyer makes a strong case for the joys of less, of living outside the hubbub and competition of modern life, many would argue that the drawbacks are too numerous. Write an essay that takes issue with Iyer’s viewpoint, countering specific points that he makes.

It is an age-

old question: does money buy happiness? Iyer states, “Though I knew that poverty certainly didn’t buy happiness, I wasn’t convinced that money did either.” Although his judgment seems clear on the matter, recent studies seem to suggest that the answer is a bit more complex. Research this question by locating at least three credible sources on the topic, and draw your own conclusion based upon what you have learned. To what extent does your research support or contradict Iyer’s conclusions?