1.1 THINKING ABOUT LITERACY

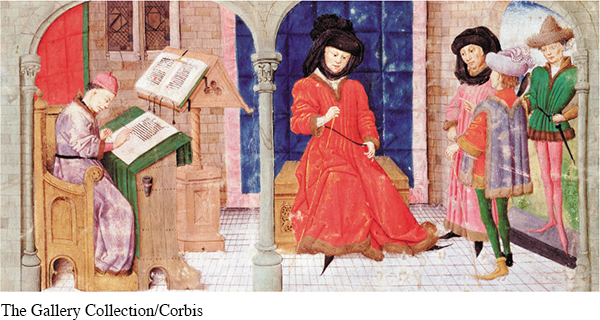

Imagine that you were reading this textbook in Europe some time before the fifteenth century. First, you’d likely be reading it in Latin, since that was the language most commonly used by those who could read. Second, you’d probably be a priest or someone very, very rich because only those in specific professions and classes of society would have been taught to read. In fact, you’d probably be sharing this book with many other classmates, since books were copied by hand and thus very expensive to produce. And last, you almost certainly would not be female.

Very few people at the time would have been considered “literate” in the traditional sense of the word, meaning able to read and write. But consider this broader definition of “literacy”:

Literacy is the ability to use available symbol systems [. . .] for the purposes of making and communicating meaning and knowledge.

—Patricia Stock, Professor, Michigan State University

While the majority of the population was not literate in the traditional sense, they had developed a variety of other types of literacies to compensate, what Professor Stock would call different “symbol systems.” Farmers, for instance, could easily make do by communicating orally with nearby neighbors about the weather and crop prices and utilizing a system of accounting symbols to keep track of sales, livestock, and equipment.

The use of a printing press with movable type likely dates back to 1040 in China, but it was Johannes Gutenberg’s discovery of this technology around 1450 that revolutionized reading and writing in the Western world. Gutenberg’s press could produce thousands of pages of text per workday, greatly expanding the access that people had to books. Philosopher Francis Bacon, looking back on this invention in 1620, said it “changed the whole face and state of the world.” Suddenly what it meant to be literate changed radically. The symbol systems once available only to the few were now accessible to the many.

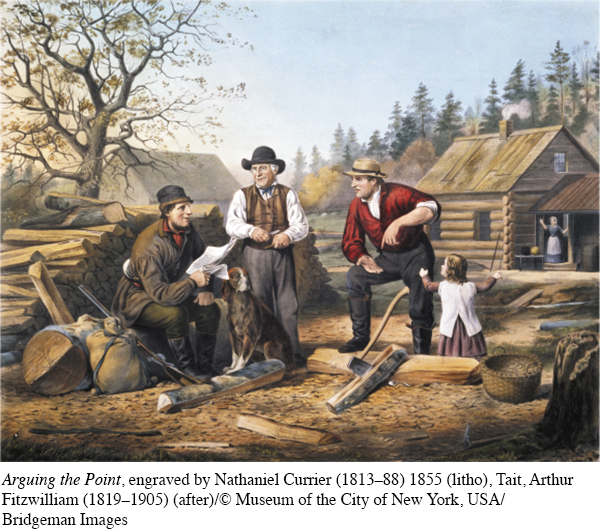

During the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was an even greater need for people to be able to read and write, as many jobs now required extensive expertise and training. Access to printed materials increased further as inexpensive newspapers and books became widely distributed. It became difficult to make and communicate information effectively in an industrialized society without using the printed word as a symbol system; the main function of schooling at this time was to make citizens literate by teaching them to read, write, and speak effectively.

How would the fact that books were copied by hand affect who had the opportunity to become literate?

This engraving, Arguing the Point (1885), by Nathaniel Currier, depicts a scene on the American frontier in which a printed newspaper is being heatedly discussed.

How is literacy represented differently in this photograph from a classroom in the early twentieth century and in the Currier engraving?