1.3 THINKING ABOUT ANALYSIS

The true purpose of literacy is not to get an A in English or to ace the SATs, but to understand, analyze, and influence the world around you. And the process for this is a simple one, something you’ve been doing your whole life: you observe, you recognize patterns, and you draw conclusions. When you are driving down the street and you see an eight-

Let’s examine that thought process a little more carefully. You observed the letters, color, and shape of the sign. You recognized a pattern in which other drivers (hopefully) stop at the sign. You then concluded based on the word formed by the letters, the shape and color of the sign, and the actions of others around you that you probably ought to stop the car.

Scientific method is not just a method which it has been found profitable to pursue in this or that abstruse subject for purely technical reasons. It represents the only method of thinking that has proved fruitful in any subject —that is what we mean when we call it scientific. It is not a peculiar development of thinking for highly specialized ends; it is thinking.

—John Dewey

What you’ve just done is analysis. You used the literacies you’ve acquired to read those letters, symbols, and colors, as well as your ability to think about the world around you, in order to draw a conclusion and make something happen in the world: in this case, stop a car and avoid an accident.

This description of analysis might sound overly technical, but in practice it is both simple and common. Moreover it is useful, essential, even powerful. Observing, finding patterns, and drawing conclusions is something you’ve done in every science class you’ve ever taken. You have practiced this kind of analysis whenever your teacher has asked you to observe some kind of process, make a hypothesis about why it happens, and then draw a conclusion about the accuracy of your hypothesis.

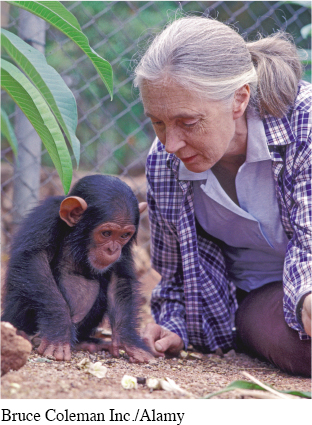

Such conclusions can have far-

Advances in business and technology also come about by observing, recognizing patterns, and drawing conclusions. The video rental and streaming company Netflix, for instance, was founded after Reed Hastings racked up $40 worth of late fees after renting a single movie. He observed his problem with late fees and reasoned that they likely were a problem for others as well. He then concluded (rightly, as it turned out) that customers would be eager to switch to a no-

It is important to understand that each of these examples required a focused observation to start off with. Jane Goodall didn’t start off observing everything she could about chimpanzees; rather, she focused on what social behaviors they demonstrated with their family members. Netflix’s founder focused his observations on customers’ reactions to late fees, not on every possible customer behavior.

The world is full of examples of this approach that we’re calling the analysis process. It is the fundamental process by which the human mind comes to understand the world, and it is the type of thinking that is being developed when you write an argument, interpret a poem, or analyze a story.