2.1 ANALYZING LITERATURE

While telling and hearing or reading stories is a fundamental part of the human experience, you still might wonder why we should analyze literature, and try to explain how it works, and, in the minds of some people, ruin it in the process. You may find yourself agreeing with Melinda from the young adult novel Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson, who in this excerpt describes how her teacher, “Hairwoman,” teaches literature—

It’s Nathaniel Hawthorne Month in English. Poor Nathaniel. Does he know what they’ve done to him? We are reading The Scarlet Letter one sentence at a time, tearing it up and chewing on its bones.

It’s all about SYMBOLISM, says Hairwoman. Every word chosen by Nathaniel, every comma, every paragraph break—

Melinda raises two key issues about literature that you might agree or disagree with:

The study of literature is mostly about hunting for a bunch of hidden symbols and meanings in order to get a good grade.

Authors don’t really mean to do whatever English teachers say they do. It’s all made up.

What Melinda doesn’t yet understand is something that we discussed in Chapter 1: the analytical process of making observations, finding patterns, and drawing conclusions is how we investigate most things in this world. So, why should literature be exempt? And what if we find a pattern that the author didn’t intend to include? It still exists, right? It exists because it is in our nature to make meaning—

Melinda, at this point, hasn’t started thinking abstractly.

Storytelling is ultimately a creative act of pattern recognition. Through characters, plot and setting, a writer creates places where previously invisible truths become visible. Or the storyteller posits a series of dots that the reader can connect.

—Douglas Coupland

Literature loves the abstract. Authors work through implication, metaphor, symbol, and imagery to convey both literal and figurative meanings, concrete and abstract ideas. You’ll need to be willing to think abstractly in order to understand and appreciate literature. When Romeo sees Juliet on the balcony, he says, “But, soft! What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.” Obviously, Romeo is saying not that Juliet is literally the sun, but rather that her beauty is like that of the sun, or maybe that seeing her is like the start of a brand-

As for Melinda’s second point—

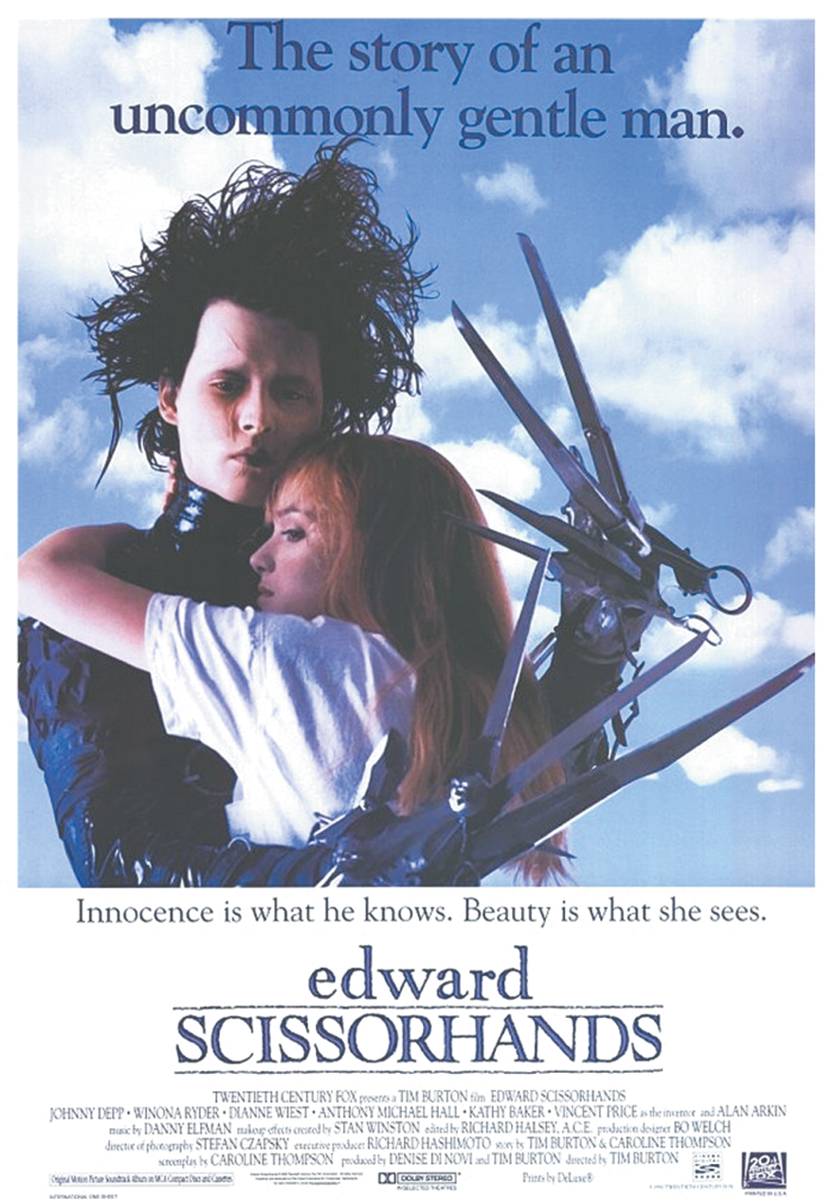

Consider the film Edward Scissorhands (1990), directed by Tim Burton. The film is about a mechanical man, played by Johnny Depp, whose creator died before he could finish building him, leaving him with scissors instead of hands. Circumstances cause Edward to leave his safe, solitary home and integrate into regular society. It’s clear that the scissors are a metaphor. Burton could have chosen for Edward to have normal hands, or even, say, salad tongs for hands. So, to address Melinda’s point, yes, Burton chose scissors on purpose because they work metaphorically: scissors can be both useful tools and dangerous weapons, which exactly mirrors the conflicting reactions Edward encounters as he tries to protect those he loves, often from himself.

Eventually Melinda from Speak begins thinking abstractly, and realizes something else too—

I can’t whine too much. Some of it is fun. It’s like a code, breaking into his head and finding the key to his secrets. Like the whole guilt thing. Of course you know the minister feels guilty and Hester feels guilty, but Nathaniel wants us to know this is a big deal. If he kept repeating, “She felt guilty, she felt guilty, she felt guilty,” it would be a boring book and no one would buy it.

This is a promotional poster for Edward Scissorhands (1990).