Syntax

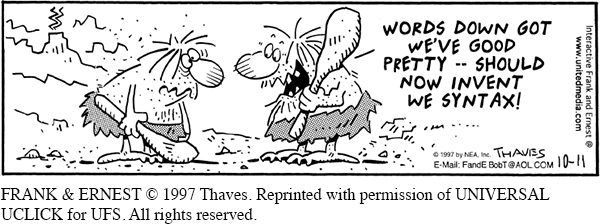

Another stylistic choice that an author makes is syntax, which is simply word order—

To some extent, grammar dictates how writers can construct their sentences, but there are often a number of different choices, including intentionally reversing the normal word order sequencing for emphasis, such as “Quit my job I cannot,” instead of the more typical “I cannot quit my job.”

Length of Sentences. Syntax often gives a text a particular rhythm. Short sentences, for example, can create a choppy rhythm or a sense of urgency, whereas longer sentences can feel smooth and flowing. If you are familiar with musical dynamics, you might think of short sentences as being staccato, while long sentences are legato. Often, writers will use changes in sentence length or sentence types to create rhythmic effects. The most common is to follow a series of long sentences with a short one to create impact, but the pattern can work the other way as well.

Types of Sentences. There are a number of sentence types a writer can use. The most common is the declarative sentence, but writers can also use sentence fragments, interrogative sentences (questions), and exclamatory sentences (with exclamation points at the end).

Punctuation. How (or whether) a writer uses punctuation is also a matter of syntax. William Faulker, for instance, regularly includes run-

How does the actual syntax of this cartoon illustrate the definition of syntax?

Syntax can be tricky to analyze, but the thing to be on the lookout for are times when form follows function, meaning when the syntax somehow emphasizes a point the author is making.

For example, read the following passage from a classic detective novel, The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett, and notice how the detective, Sam Spade, uses short, simple, declarative sentences that reveal his no-

When a man’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t make any difference what you thought of him. He was your partner and you’re supposed to do something about it. Then it happens we were in the detective business. Well, when one of your organization gets killed it’s bad business to let the killer get away with it. It’s bad all around—