3.1 CHANGING MINDS, CHANGING THE WORLD

Argument and rhetoric are not just for English class or for silver-

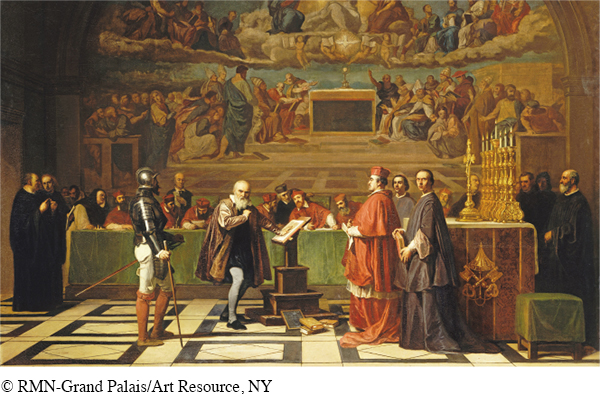

In the early seventeenth century, Galileo Galilei presented evidence supporting Nicolaus Copernicus’s theory that the earth revolved around the sun, despite the claim of most scientists and religious leaders at the time that the earth was the center of the universe. While he was arrested and imprisoned for arguing his position, eventually the ban on his work was lifted, and his ideas prevailed because of the compelling evidence he had presented.

In 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe published the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which became the best-

How does this painting visually represent the challenges that Galileo faced?

This statue of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Abraham Lincoln stands in front of the Lincoln Financial building in Hartford, Connecticut, where Stowe lived.

The American biologist Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962, arguing that widespread use of DDT and other synthetic pesticides would have a disastrous impact on our environment. She claimed that these pesticides not only killed insects but also made their way up the food chain to threaten bird and fish populations and that they could eventually sicken humans. At a congressional hearing on pesticides, one senator described Silent Spring, which eventually sold more than 2 million copies, as a book that “substantially altered the course of history.”

Rachel Carson testifying before Congress in 1963 on the environmental hazards of pesticides and other chemicals.

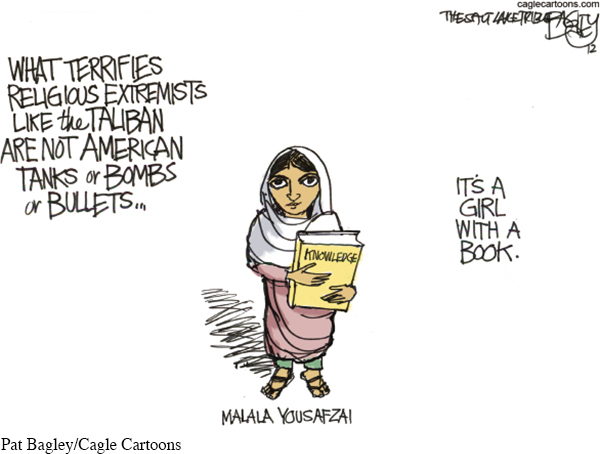

Even more recently, Malala Yousafzai began blogging in 2009 about the Taliban, which had taken control of her town in Pakistan and banned girls from attending school. Despite the threats of violence, the preteen continued posting to her blog to express her point of view, and on October 9, 2012, a Taliban fighter boarded her school bus, asked for her by name, and shot her three times. Yousafzai recovered fully and has since continued to advocate for education for girls, leading Pakistan to pass its very first Right to Education bill—

As you can see, making strong arguments is important because it gives us an opportunity to influence the world around us, whether the change we create is globally dramatic or personally significant.

Just as important as developing our own arguments, however, is the ability to critically examine the arguments that others present to us. We are bombarded daily by arguments that people, governments, corporations, and others are making in order to influence us in one way or another. Companies try to get us to buy their products, politicians try to get our votes, researchers present evidence to convince us of their findings and conclusions, and artists challenge our point of view. We have to be careful consumers, voters, readers, viewers, and listeners, so that we can make informed choices in all areas of our lives, and not be manipulated by faulty arguments.

This political cartoon by artist Pat Bagley is from 2012, soon after Yousafzai was shot by the Taliban.

The process of thinking carefully about the rhetoric around us, and of analyzing how rhetoric is used as a tool of persuasion, is the same analysis process that we introduced in Chapter 1.

make observations

identify patterns

draw conclusions

In analyzing rhetoric, you carefully observe what writers or speakers say and how they say it. You look for patterns in their language, evidence, or reasoning, and you draw conclusions about whether their use of rhetoric is effective, manipulative, flawed, masterful, or somewhere in between.

KEY QUESTIONS

When you think about rhetoric, the key questions to ask are:

What strategies does the writer or speaker use to reach (or persuade) his or her audience?

What goal (or purpose) does the writer or speaker have in mind?