3.14 COUNTERARGUMENTS

An important element of effective argument is acknowledging the counterargument—that is, an opposing viewpoint. Ignoring or dismissing any position not in agreement with yours demonstrates bias, while addressing one or more counterarguments demonstrates that you are reasonable. For instance, if you were arguing in favor of increased school security, you might cite the counterargument that security guards are detrimental to the learning environment because they make students feel like criminals and act accordingly, but then refute that argument by pointing out that violence is much more disruptive to the school environment and that any feelings of being treated like a criminal are no more than inconveniences in comparison. In this way, you indicate that you have recognized and considered a position counter to your own as part of the process of developing your viewpoint. The result is that you not only appeal to logos by sounding reasonable but also establish your ethos as a fair-

When you work with counterargument, an effective strategy is called concession and refutation (or “concede and refute”). You start out by agreeing with the opposition (conceding) to show that you respect the views of others, even those you disagree with. Then—

For instance, in an article about the downside to police officers’ wearing body cameras, New York Times writer David Brooks opens by acknowledging the reasons one might argue in favor of body cams:

First, there have been too many cases in which police officers have abused their authority and then covered it up. Second, it seems probable that cops would be less likely to abuse their authority if they were being tracked. Third, human memory is an unreliable faculty. We might be able to reduce the number of wrongful convictions and acquittals if we have cameras recording more events.

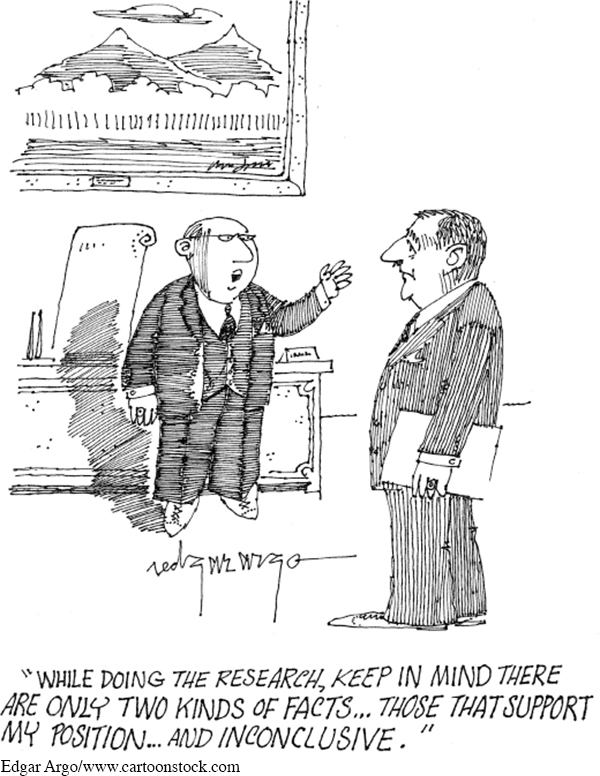

What does this cartoon have to say about the importance of acknowledging counterarguments?

Does Brooks undermine his own argument? Not at all. By starting with objections right up front, he avoids sounding confrontational. In fact, he sounds downright agreeable. This encourages his readers, even those who disagree, to be receptive to what he has to say. In the article, Brooks goes on to appeal to readers’ emotions, evoking cases of controversial police behavior that occurred in 2015, within a few months of his article’s publication. He counters the argument in support of body cams not by saying that people who advocate them are entirely wrong, but by arguing that they do not take other critical issues into account—

Cop-