5.10

from Souvenir of the

Carlisle Indian School

The following images come from a pamphlet called Souvenir of the Carlisle Indian School, published in 1902.

KEY CONTEXT By the end of the nineteenth century, American westward expansion had driven much of the native population of American Indians onto reservations. As part of the policy of the day, many American Indian children were compelled to attend public schools, either day or boarding schools. The first off-

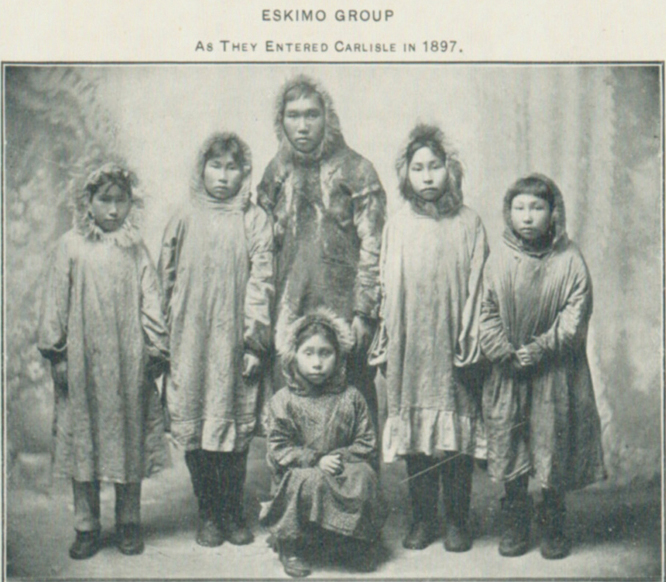

Eskimo Group

As they entered Carlisle in 1897.

As they appear in school dress.

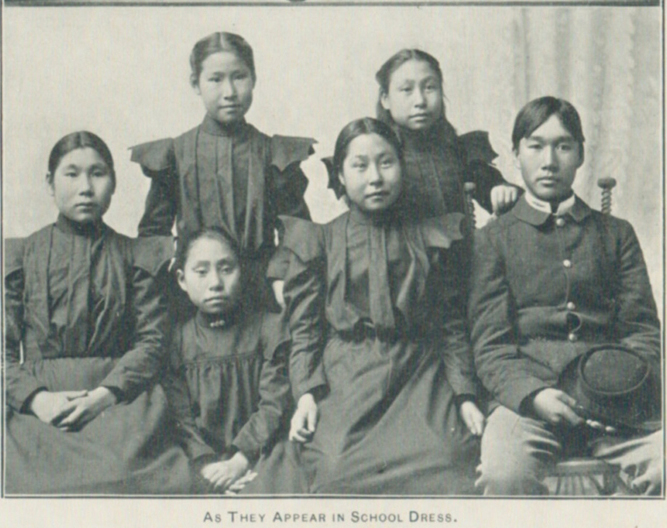

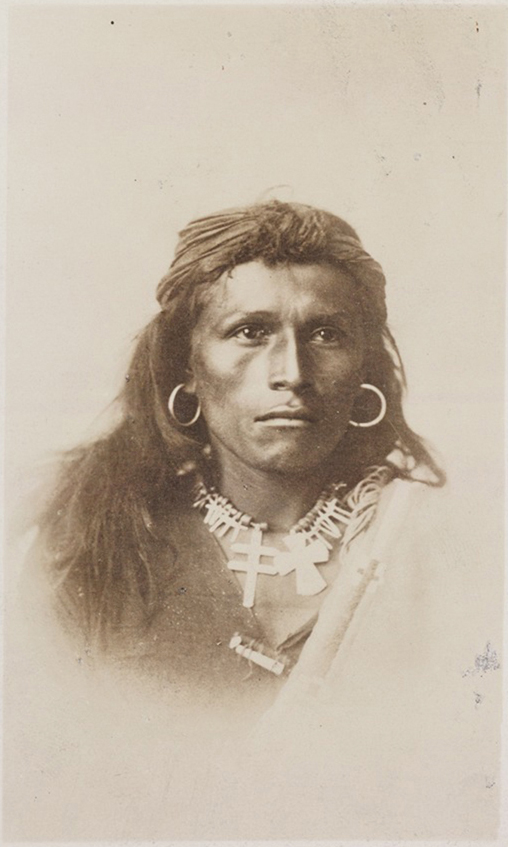

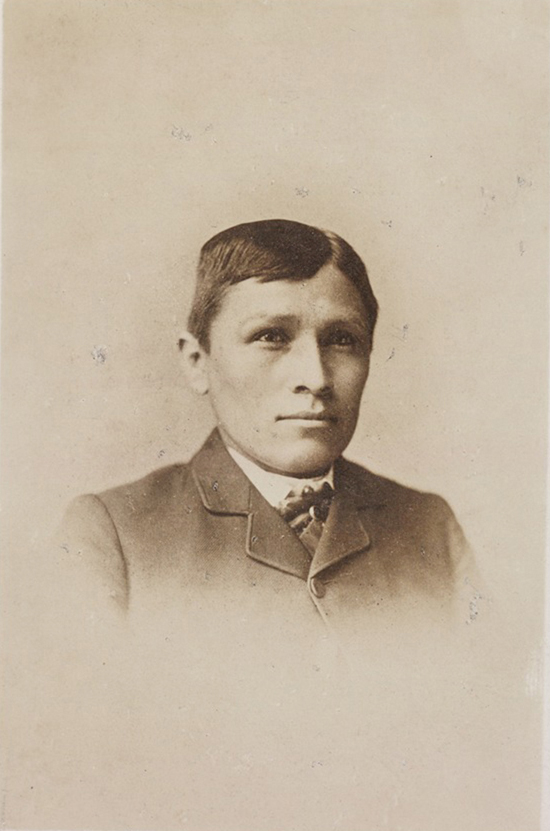

Tom Torlino–

As he entered the school in 1882.

As he appeared three years later.

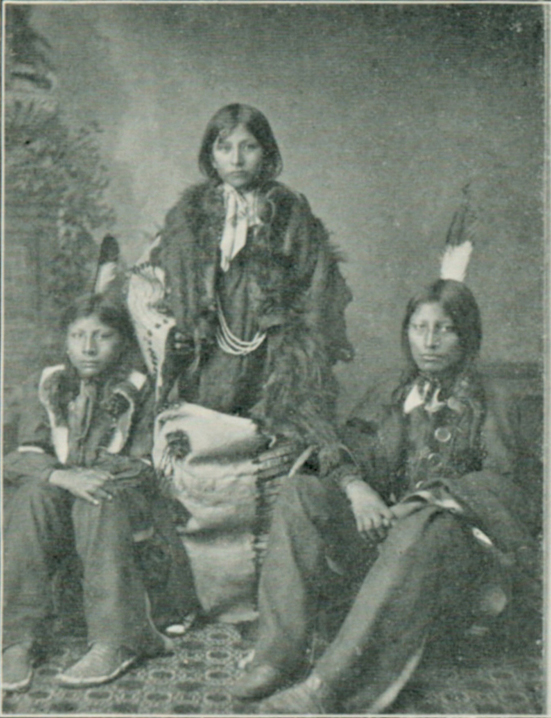

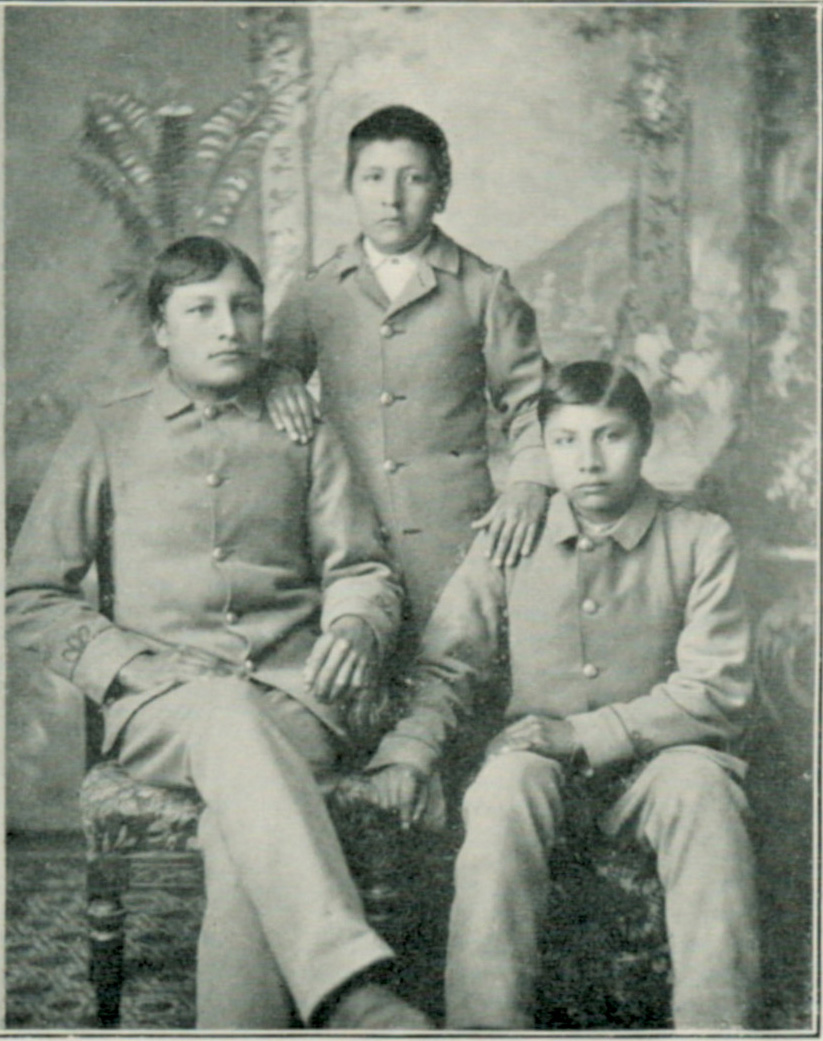

Wounded Yellow Robe, Henry Standing Bear, Chauncy Yellow Robe

Sioux boys as they entered the school in 1883.

Three years later.

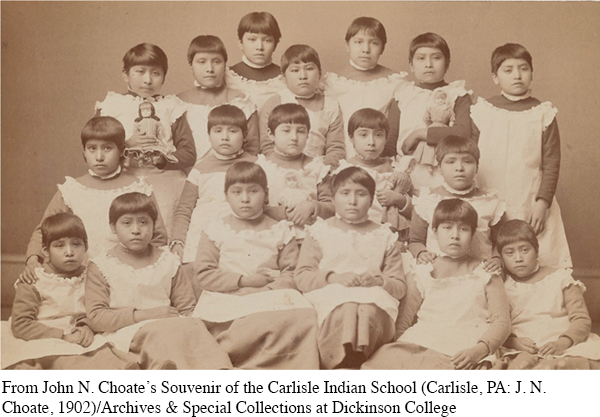

Group of Pueblo Girls

Entered Carlisle in 1884.

seeing connections

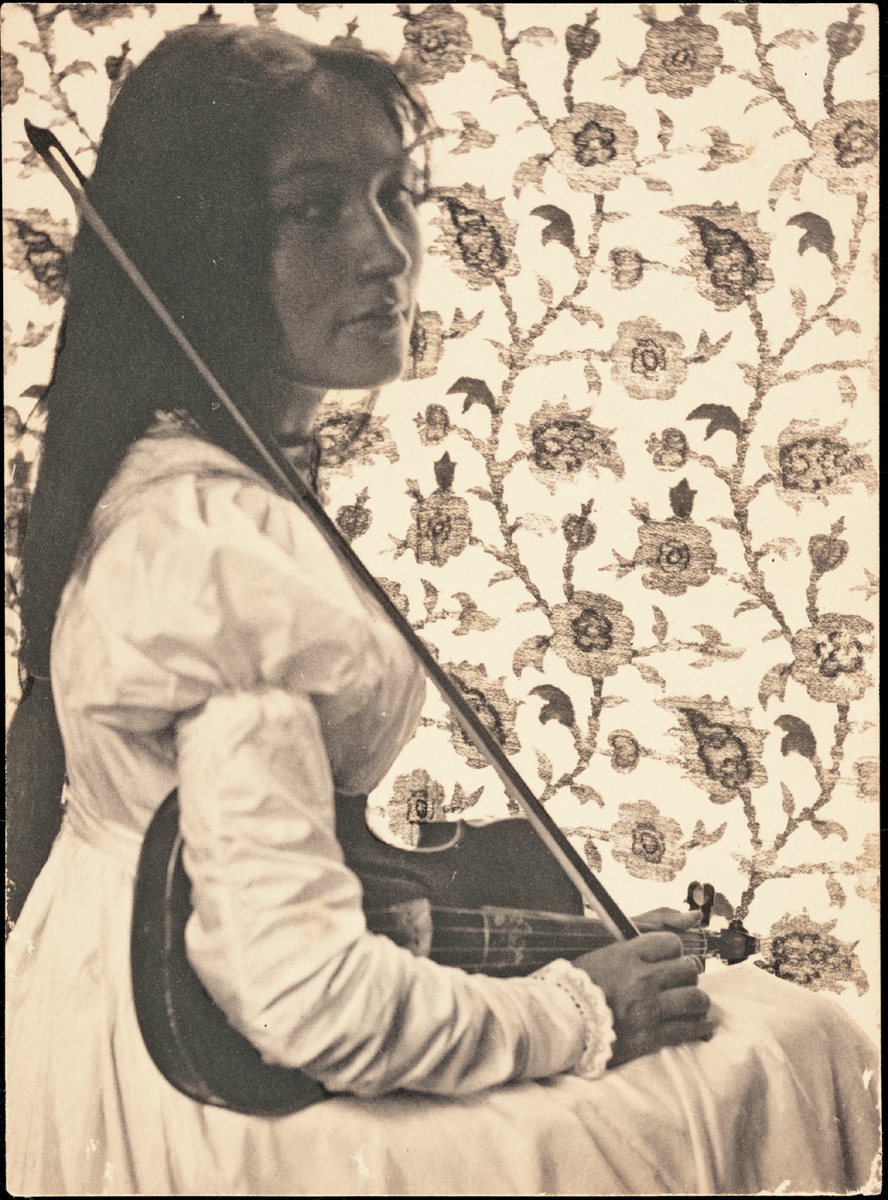

The following excerpt is from The School Days of an Indian Girl, a memoir by Zitkala-

In this section of her memoir, Zitkala-

from The School Days of an Indian Girl

Late in the morning, my friend Judéwin gave me a terrible warning. Judéwin knew a few words of English, and she had overheard the paleface woman talk about cutting our long, heavy hair. Our mothers had taught us that only unskilled warriors who were captured had their hair shingled by the enemy. Among our people, short hair was worn by mourners, and shingled hair by cowards!

We discussed our fate some moments, and when Judéwin said, “We have to submit, because they are strong,” I rebelled.

“No, I will not submit! I will struggle first!” I answered.

I watched my chance, and when no one noticed I disappeared. I crept up the stairs as quietly as I could in my squeaking shoes — my moccasins had been exchanged for shoes. Along the hall I passed, without knowing whither I was going. Turning aside to an open door, I found a large room with three white beds in it. The windows were covered with dark green curtains, which made the room very dim. Thankful that no one was there, I directed my steps toward the corner farthest from the door. On my hands and knees I crawled under the bed, and cuddled myself in the dark corner.

5 From my hiding place I peered out, shuddering with fear whenever I heard footsteps nearby. Though in the hall loud voices were calling my name, and I knew that even Judéwin was searching for me, I did not open my mouth to answer. Then the steps were quickened and the voices became excited. The sounds came nearer and nearer. Women and girls entered the room. I held my breath, and watched them open closet doors and peep behind large trunks. Some one threw up the curtains, and the room was filled with sudden light. What caused them to stoop and look under the bed I do not know. I remember being dragged out, though I resisted by kicking and scratching wildly. In spite of myself, I was carried downstairs and tied fast in a chair.

How do the ideas in this diary entry affect your reading of the photos from the Carlisle Indian School?

I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids. Then I lost my spirit. Since the day I was taken from my mother I had suffered extreme indignities. People had stared at me. I had been tossed about in the air like a wooden puppet. And now my long hair was shingled like a coward’s! In my anguish I moaned for my mother, but no one came to comfort me. Not a soul reasoned quietly with me, as my own mother used to do; for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder.

Understanding and Interpreting

Several of the images document children on their arrival at Carlisle School and then sometime later after they have been at the school for a while. What are the significant differences between each “before” and “after” shot? How do these images connect to the school’s motto identified in the Key Context note on page 167?

Juxtaposition is the placement of two or more things near each other for the purpose of comparison or contrast. The “before” and “after” photographs here have been deliberately juxtaposed. Explain the effect of this juxtaposition by considering how the meaning would have been different had you only seen the “after” images.

These images that you are looking at in the early twenty-

first century were taken near the turn of the twentieth century. How might your interpretation of these images differ from that of someone looking at them one hundred years ago? Why do you think this is? What has changed in our society and culture? To what extent do the photographs prove that the school was successful in achieving its motto: “To civilize the Indian, get him into civilization. To keep him civilized, let him stay”?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Look back through the images carefully to see if there are differences in the way the individuals are positioned in the “before” and “after” photographs. How do the children relate to one another physically (for example, in the placement of their arms and legs, in relative proximity)? What inferences can you draw about the intended effect of the differences between the “before” and “after” pictures?

Look back more closely at the pictures of Tom Torlino, which are a fairly well-

known pair of images. If you look at the “after” picture, it appears that Torlino’s skin color is significantly lighter than it was when he first arrived. Some historians have suggested this was an intentional choice by the photographer. If this is true, why do you think the photographer would do this? Look back once more at the pictures of Tom Torlino. What is the most striking difference apart from the clothing? How does the first photo contrast with traditional Western notions of masculinity? Is the first or second image more threatening? What details contribute to your response to this last question?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Look back through pictures of yourself, a friend, or a family member, and try to locate a pair of pictures that show a significant change in appearance over time. What were the internal and external forces that led to these changes? In what ways do the changes reflect pressures similar to the ones that the Native Americans at the Carlisle School faced?

Based only on the brief context you were provided at the start of this text and on the images you examined, write a diary entry from the perspective of a young American Indian on the day of his or her arrival at the Carlisle School, and then another entry a few months later. Try to focus your entries by addressing one or more of the essential questions about identity you have been thinking about throughout this chapter.

An organization called the Boarding School Healing Project has been working to raise awareness of the lasting effects of schools such as Carlisle, and pushing for reparations, which is a legal term for paying money to or otherwise compensating a group of people who have been wronged or their descendants. The Healing Project claims that the students at schools like Carlisle were subjected to human rights violations, including malnutrition, cultural and religious repression, inadequate medical care, and physical abuse. Do you agree or disagree with the payment of reparations to these students or their descendants? Why?