5.15

Against School

John Taylor Gatto

A three-

Itaught for thirty years in some of the worst schools in Manhattan, and in some of the best, and during that time I became an expert in boredom. Boredom was everywhere in my world, and if you asked the kids, as I often did, why they felt so bored, they always gave the same answers: They said the work was stupid, that it made no sense, that they already knew it. They said they wanted to be doing something real, not just sitting around. They said teachers didn’t seem to know much about their subjects and clearly weren’t interested in learning more. And the kids were right: their teachers were every bit as bored as they were.

Boredom is the common condition of schoolteachers, and anyone who has spent time in a teachers’ lounge can vouch for the low energy, the whining, the dispirited attitudes, to be found there. When asked why they feel bored, the teachers tend to blame the kids, as you might expect. Who wouldn’t get bored teaching students who are rude and interested only in grades? If even that. Of course, teachers are themselves products of the same twelve-

We all are. My grandfather taught me that. One afternoon when I was seven I complained to him of boredom, and he batted me hard on the head. He told me that I was never to use that term in his presence again, that if I was bored it was my fault and no one else’s. The obligation to amuse and instruct myself was entirely my own, and people who didn’t know that were childish people, to be avoided if possible. Certainly not to be trusted. That episode cured me of boredom forever, and here and there over the years I was able to pass on the lesson to some remarkable student. For the most part, however, I found it futile to challenge the official notion that boredom and childishness were the natural state of affairs in the classroom. Often I had to defy custom, and even bend the law, to help kids break out of this trap.

The empire struck back, of course; childish adults regularly conflate opposition with disloyalty. I once returned from a medical leave to discover that all evidence of my having been granted the leave had been purposely destroyed, that my job had been terminated, and that I no longer possessed even a teaching license. After nine months of tormented effort I was able to retrieve the license when a school secretary testified to witnessing the plot unfold. In the meantime my family suffered more than I care to remember. By the time I finally retired in 1991, I had more than enough reason to think of our schools — with their long-

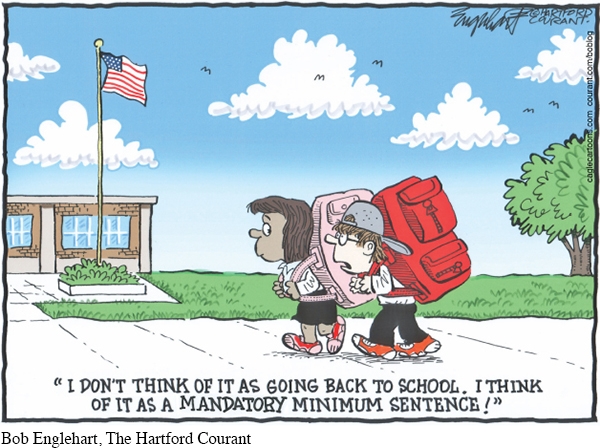

Identify a piece of evidence from Gatto’s article that would support this character’s claim about school.

5 But we don’t do that. And the more I asked why not, and persisted in thinking about the “problem” of schooling as an engineer might, the more I missed the point: What if there is no “problem” with our schools? What if they are the way they are, so expensively flying in the face of common sense and long experience in how children learn things, not because they are doing something wrong but because they are doing something right? Is it possible that George W. Bush accidentally spoke the truth when he said we would “leave no child behind”? Could it be that our schools are designed to make sure not one of them ever really grows up?

Do we really need school? I don’t mean education, just forced schooling: six classes a day, five days a week, nine months a year, for twelve years. Is this deadly routine really necessary? And if so, for what? Don’t hide behind reading, writing, and arithmetic as a rationale, because 2 million happy homeschoolers have surely put that banal justification to rest. Even if they hadn’t, a considerable number of well-

Throughout most of American history, kids generally didn’t go to high school, yet the unschooled rose to be admirals, like Farragut; inventors, like Edison; captains of industry, like Carnegie and Rockefeller; writers, like Melville and Twain and Conrad; and even scholars, like Margaret Mead. In fact, until pretty recently people who reached the age of thirteen weren’t looked upon as children at all. Ariel Durant, who co-

We have been taught (that is, schooled) in this country to think of “success” as synonymous with, or at least dependent upon, “schooling,” but historically that isn’t true in either an intellectual or a financial sense. And plenty of people throughout the world today find a way to educate themselves without resorting to a system of compulsory secondary schools that all too often resemble prisons. Why, then, do Americans confuse education with just such a system? What exactly is the purpose of our public schools?

Mass schooling of a compulsory nature really got its teeth into the United States between 1905 and 1915, though it was conceived of much earlier and pushed for throughout most of the nineteenth century. The reason given for this enormous upheaval of family life and cultural traditions was, roughly speaking, threefold: 1) To make good people. 2) To make good citizens. 3) To make each person his or her personal best.

10 These goals are still trotted out today on a regular basis, and most of us accept them in one form or another as a decent definition of public education’s mission, however short schools actually fall in achieving them. But we are dead wrong. Compounding our error is the fact that the national literature holds numerous and surprisingly consistent statements of compulsory schooling’s true purpose. We have, for example, the great H. L. Mencken, who wrote in The American Mercury for April 1924 that the aim of public education is not

to fill the young of the species with knowledge and awaken their intelligence. . . . Nothing could be further from the truth. The aim is simply to reduce as many individuals as possible to the same safe level, to breed and train a standardized citizenry, to put down dissent and originality. That is its aim in the United States . . . and that is its aim everywhere else.

There you have it. Now you know. We don’t need Karl Marx’s conception of a grand warfare between the classes to see that it is in the interest of complex management, economic or political, to dumb people down, to demoralize them, to divide them from one another, and to discard them if they don’t conform. Class may frame the proposition, as when Woodrow Wilson, then president of Princeton University, said the following to the New York City School Teachers Association in 1909: “We want one class of persons to have a liberal education, and we want another class of persons, a very much larger class, of necessity, in every society, to forgo the privileges of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks.” But the motives behind the disgusting decisions that bring about these ends need not be class-

seeing connections

The logical extension of Gatto’s argument is that students should not be required to attend school.

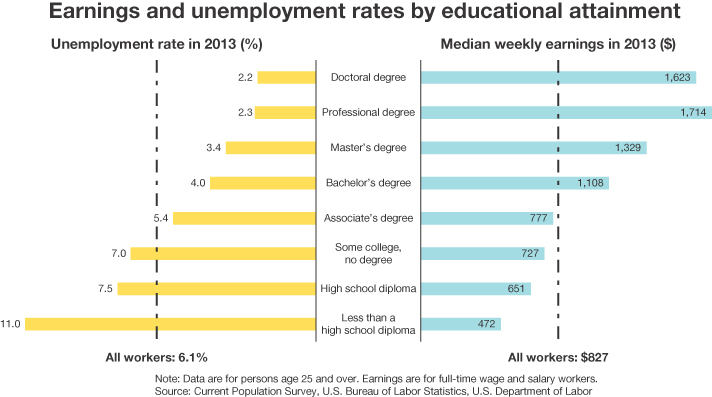

Explain why you think Gatto is right, wrong, or maybe just a little off the mark. How does the accompanying chart from the Bureau of Labor Statistics affect your viewpoint?

There were vast fortunes to be made, after all, in an economy based on mass production and organized to favor the large corporation rather than the small business or the family farm. But mass production required mass consumption, and at the turn of the twentieth century most Americans considered it both unnatural and unwise to buy things they didn’t actually need. Mandatory schooling was a godsend on that count. School didn’t have to train kids in any direct sense to think they should consume nonstop, because it did something even better: it encouraged them not to think at all. And that left them sitting ducks for another great invention of the modern era — marketing.

We buy televisions, and then we buy the things we see on the television. We buy computers, and then we buy the things we see on the computer. We buy $150 sneakers whether we need them or not, and when they fall apart too soon we buy another pair. We drive SUVs and believe the lie that they constitute a kind of life insurance, even when we’re upside-

Now for the good news. Once you understand the logic behind modern schooling, its tricks and traps are fairly easy to avoid. School trains children to be employees and consumers; teach your own to be leaders and adventurers. School trains children to obey reflexively; teach your own to think critically and independently. Well-

15 First, though, we must wake up to what our schools really are: laboratories of experimentation on young minds, drill centers for the habits and attitudes that corporate society demands. Mandatory education serves children only incidentally; its real purpose is to turn them into servants. Don’t let your own have their childhoods extended, not even for a day. If David Farragut could take command of a captured British warship as a preteen, if Thomas Edison could publish a broadsheet at the age of twelve, if Ben Franklin could apprentice himself to a printer at the same age (then put himself through a course of study that would choke a Yale senior today), there’s no telling what your own kids could do. After a long life, and thirty years in the public school trenches, I’ve concluded that genius is as common as dirt. We suppress our genius only because we haven’t yet figured out how to manage a population of educated men and women. The solution, I think, is simple and glorious. Let them manage themselves.

Understanding and Interpreting

What is the main claim that John Taylor Gatto makes? Find one sentence that states his claim.

Gatto begins his essay with an examination of boredom. What does he say causes this boredom and what is the result?

Gatto says that the purpose of mandatory education offered by society is “1) To make good people. 2) To make good citizens. 3) To make each person his or her personal best” (par. 9), and then he attacks these ideas by quoting H. L. Mencken and Woodrow Wilson. Summarize what conclusions Gatto expects his readers to draw from these sources.

How does Gatto link consumerism with the habits of mind taught in public schools? Do you agree or disagree with Gatto’s claim that a significant purpose of school is to create consumers?

According to Gatto, who is most responsible for the problems in American education? Is it the teachers? School administrators? Parents? Students? Politicians? What evidence can you cite to support your response?

Reread the paragraph that begins with “Now for the good news” (par. 14). What are the solutions that Gatto suggests for how parents can fight back and encourage their children’s education without school? Are these solutions that could work within the school system? Why or why not?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

John Taylor Gatto begins by describing his own experience, a discouraging one, as a teacher. What effect does the inclusion of his personal experience have on his argument? How does the biographical information that precedes the article, as well as the biographical information Gatto chooses to include, help to establish his ethos?

Gatto cites examples of presidents, inventors, writers, and wealthy businesspersons to make his case that compulsory schooling is not necessary for success (par. 7). He returns to this list at the end of the essay (par. 15). Explain why you do or do not find such examples persuasive.

Gatto lists three reasons for mandatory public schooling, as it was conceived in the United States —and then asserts that they are not truly the principles that govern education today. What evidence (including examples) does he cite to support this assertion?

What vulnerabilities do you find in Gatto’s argument? Look back through the piece and identify a place where you think that Gatto does not effectively support a claim he is making, or where his logic seems faulty. Why do you think his writing is not effective in this section?

Gatto’s language moves between informal expressions (such as “The empire struck back”) and quite elevated language (“Class may frame the proposition”). Do you find such movement an effective rhetorical strategy, or does it seem inconsistent? Support your response by referring to specific passages.

This essay first appeared in 2003 in Harper’s magazine, a monthly publication appealing to an educated, fairly liberal readership. What are some of the ways Gatto specifically appeals to this demographic?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Choose one of the following assertions that John Taylor Gatto or one of the sources he cites makes and discuss how your own experience confirms or challenges it:

“[O]ur schools [. . .] [are] virtual factories of childishness” (par. 4).

“[S]econdary schools [. . .] all too often resemble prisons” (par. 8).

“[T]he aim of public education is [. . .] ‘to reduce as many individuals as possible to the same safe level, to breed and train a standardized citizenry, to put down dissent and originality’” (par. 10, quoting H. L. Mencken).

“Mandatory education serves children only incidentally; its real purpose is to turn them into servants” (par. 15).

“[W]e must wake up to what our schools really are: laboratories of experimentation on young minds, drill centers for the habits and attitudes that corporate society demands” (par. 15).

Toward the end of the essay, Gatto calls on parents to teach their own children to be “leaders and adventurers,” to think “critically and independently,” and to “develop an inner life so that they’ll never be bored” (par. 14). Write a proposal for a school that would serve these purposes or that you think has the promise of achieving some of them. What would be its main guiding principles and characteristics?

According to some studies, schools in countries like Finland, Singapore, and Japan, among others, regularly outperform the United States, and could be judged as more successful education systems. Research an educational system in another country or culture. Discuss what values it tries to develop in its students and based on your research and experience, develop a position about whether you think that system is more or less effective than the United States system. Also consider how Gatto would likely evaluate that system.