5.16

from The Common School Journal

Horace Mann

Horace Mann (1796–

KEY CONTEXT Mann once said, “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity,” which is now the motto of Antioch College, of which Mann was the first president. As you read, keep in mind that this excerpt is from 1842, and the United States was still a newly formed, largely rural and agrarian country. There was not yet widespread agreement on the need for education for all citizens, especially for children of lower socioeconomic status. It was not until the 1920s that more than half of the teenage population even attended high school. The question that Mann tries to answer here is: why is school important to the individual as well as society?

Mankind are rapidly passing through a transition state. The idea and feeling that the world was made, and life given, for the happiness of all, and not for the ambition, or pride, or luxury, of one, or of a few, are pouring in, like a resistless tide, upon the minds of men, and are effecting a universal revolution in human affairs. Governments, laws, social usages, are rapidly dissolving, and recombining in new forms. The axiom which holds the highest welfare of all the recipients of human existence to be the end and aim of that existence, is the theoretical foundation of all the governments of this Union; it has already modified all the old despotisms of Europe, and has obtained a foothold on the hitherto inaccessible shores of Asia and Africa, and the islands of the sea. A new phrase, — the people, — is becoming incorporated into all languages and laws; and the correlative idea of human rights is evolving, and casting off old institutions and customs, as the expanding body bursts and casts away the narrow and worn-

In all the towns in our Common wealth, — in the small and obscure, and perhaps still more in cities and in other populous places, — there are many children, — orphans, or those who, in the curse of vicious parentage, suffer a worse evil than orphanage, — children doomed to incessant drudgery, and who, from the straitened circumstances of the household, from awkwardness of manners, or indigence in dress, never emerge from their solitude and obscurity, and therefore necessarily grow up with all the coarseness, narrowness, prejudices, and bad manners, almost inseparable from spending the years of non-

seeing connections

Horace Mann argues in this piece for the importance of universal education.

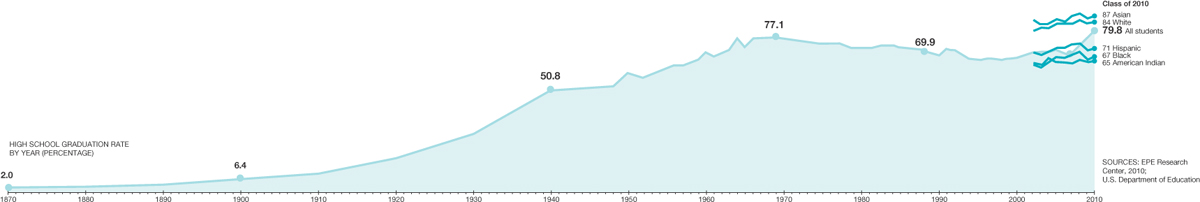

Look at this chart and, first, make a claim about the trends in the graduation rate in the United States. Then, based upon what you have read in the Mann piece, explain what you believe might have caused these trends.

Now, in the common course of events, and without the instrumentality of schools, this class of children, during the whole period of their minority, would never be brought into communication or acquaintance with a single educated, intelligent, benevolent individual, — with one who loves children with a wise and forecasting love, — with one whose manners are refined, whose tastes and sentiments are pure and elevating, — who can display the beauty and excellence of knowledge, and win others to obtain what they cannot fail to admire. The most which this class of children would be likely to see of any educated men, would be when the clergyman should make his brief annual parochial call, or when the physician should be summoned to administer to diseases brought on by ignorance or improper indulgences, or when they should be carried before the courts to answer for offences which their untaught and unchastened passions had prompted them to commit. But let a company of well-

Understanding and Interpreting

Summarize the “transition state” that Horace Mann suggests mankind is passing through (par. 1), and explain how this historical movement relates to the idea of universal education.

According to Mann, what is the effect of the widespread use of the new phrase “the people” (par. 1)?

Despite the fact that at the time he was writing women were unable to vote in the United States, Mann takes the time to describe the unique circumstances of young women who are not educated. Explain how the plight of women at the time that he describes helps to make his case for universal education.

Page 216Reread the first part of paragraph 3, which begins “Now, in the common course of events,” and identify the main goal that Mann believes schools should attempt to achieve.

Explain what Mann means in the final sentence of the excerpt: “In the great march of society, it is rather our duty to bring up the rear than to push forward the van” (par. 3).

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Horace Mann tries to draw a clear contrast between life for students outside school and for students inside. Make a T-

chart of the words and phrases that Mann uses to describe each, and then explain how his word choices help to support his argument for universal schooling. Reread the long sentence that begins with “But let a company of well-

educated . . .” (par. 3). How do the language choices in this sentence attempt to convince the reader of the value of education? Notice how both the beginning and the end of the excerpt take the reader outside the geographical boundaries of the United States. What is Mann’s purpose in doing so, and how effective is this choice in making his case for universal education?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

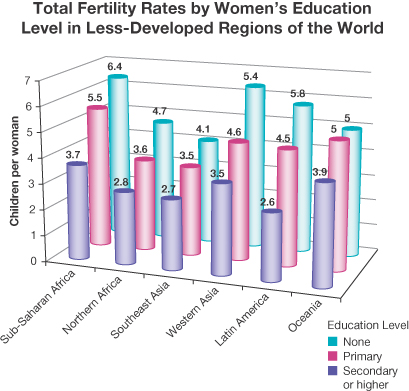

One of the arguments that Mann makes about universal education is the effect that it can have on women and society as a whole. Look at the following chart and conduct additional research in order to explain the effect that educating women in developing countries today can have on a society.

Near the end of this excerpt, Mann says that education is the work of civilization and of Christianity. And yet today, Mann is known for being a secularist in education, meaning that he felt that religion did not have a place in the public schools. Additionally, the concept of the separation of church and state appears in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, adopted in 1791, which says, in part, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” There are many examples of how the conflict between secularism and someone’s right to practice his or her religion openly plays out in schools. In your opinion, what is the proper place for religion in school, and what evidence can you provide to support your position?

Mann describes school as a place where young people should be in the company of “well-

educated, well- trained, devoted teachers” who share “their qualities of knowledge, dignity, kindness, purity, and refinement” with their students. To what extent has this been your experience with teachers throughout your experience, from elementary school into high school? Be sure not to identify specific teachers by name in your response.