5.2 CENTRAL TEXT

Shooting an Elephant

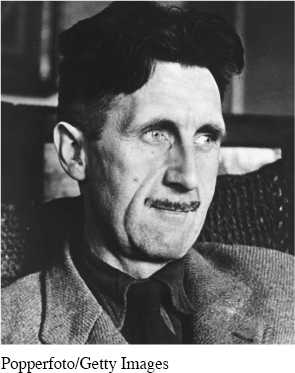

George Orwell

George Orwell, the author of several well-

KEY CONTEXT The term “imperialism,” especially British imperialism, is an important one to understand for this piece. From the late sixteenth century through World War I, at the beginning of the twentieth century, England had history’s largest empire. At various times throughout this time period, England had colonies in areas now known as the United States, Canada, Australia, Asia, Africa, and South America; a popular and true saying at the time was “The sun never sets on the British Empire.”

The British government in the Indian subcontinent — which includes what is now India, as well as Pakistan, Myanmar/Burma, Bangladesh, and other countries — was called the Raj, a Hindi word for “rule.” While England regularly conquered its colonies through military strength, it ruled them by forcing its educational, judicial, economic, and governmental structures onto the colonized people with the goal of making the world British. But, starting with the American Revolution in the late eighteenth century, most of the former colonies, often through war, were able to gain their independence. Burma (now Myanmar), where this piece is set, became independent from England in 1948, only about twenty years after Orwell worked there.

In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people — the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me. I was sub-

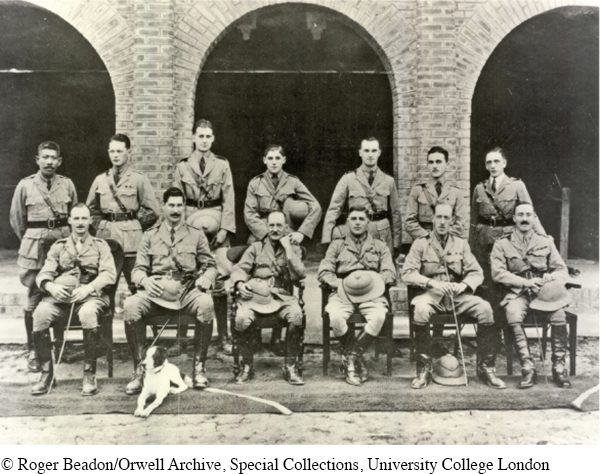

Burma Provincial Police Training School, Mandalay, 1923. Eric Blair (George Orwell) standing third from left.

All this was perplexing and upsetting. For at that time I had already made up my mind that imperialism was an evil thing and the sooner I chucked up my job and got out of it the better. Theoretically — and secretly, of course — I was all for the Burmese and all against their oppressors, the British. As for the job I was doing, I hated it more bitterly than I can perhaps make clear. In a job like that you see the dirty work of Empire at close quarters. The wretched prisoners huddling in the stinking cages of the lock-

One day something happened which in a roundabout way was enlightening. It was a tiny incident in itself, but it gave me a better glimpse than I had had before of the real nature of imperialism — the real motives for which despotic governments act. Early one morning the sub-

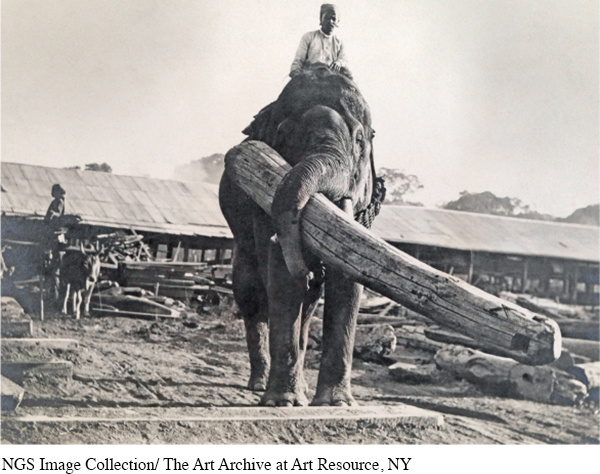

Elephants in colonial Burma were largely industrial animals, primarily used in the lumber industry. Their drivers were called “mahouts.”

The Burmese sub-

5 The orderly came back in a few minutes with a rifle and five cartridges, and meanwhile some Burmans had arrived and told us that the elephant was in the paddy fields below, only a few hundred yards away. As I started forward practically the whole population of the quarter flocked out of the houses and followed me. They had seen the rifle and were all shouting excitedly that I was going to shoot the elephant. They had not shown much interest in the elephant when he was merely ravaging their homes, but it was different now that he was going to be shot. It was a bit of fun to them, as it would be to an English crowd; besides they wanted the meat. It made me vaguely uneasy. I had no intention of shooting the elephant — I had merely sent for the rifle to defend myself if necessary — and it is always unnerving to have a crowd following you. I marched down the hill, looking and feeling a fool, with the rifle over my shoulder and an ever-

I had halted on the road. As soon as I saw the elephant I knew with perfect certainty that I ought not to shoot him. It is a serious matter to shoot a working elephant — it is comparable to destroying a huge and costly piece of machinery — and obviously one ought not to do it if it can possibly be avoided. And at that distance, peacefully eating, the elephant looked no more dangerous than a cow. I thought then and I think now that his attack of “must” was already passing off; in which case he would merely wander harmlessly about until the mahout came back and caught him. Moreover, I did not in the least want to shoot him. I decided that I would watch him for a little while to make sure that he did not turn savage again, and then go home.

But at that moment I glanced round at the crowd that had followed me. It was an immense crowd, two thousand at the least and growing every minute. It blocked the road for a long distance on either side. I looked at the sea of yellow faces above the garish clothes — faces all happy and excited over this bit of fun, all certain that the elephant was going to be shot. They were watching me as they would watch a conjurer about to perform a trick. They did not like me, but with the magical rifle in my hands I was momentarily worth watching. And suddenly I realized that I should have to shoot the elephant after all. The people expected it of me and I had got to do it; I could feel their two thousand wills pressing me forward, irresistibly. And it was at this moment, as I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man’s dominion in the East. Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd —seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind. I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys. He becomes a sort of hollow, posing dummy, the conventionalized figure of a sahib.5 For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life in trying to impress the “natives,” and so in every crisis he has got to do what the “natives” expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it. I had got to shoot the elephant. I had committed myself to doing it when I sent for the rifle. A sahib has got to act like a sahib; he has got to appear resolute, to know his own mind and do definite things. To come all that way, rifle in hand, with two thousand people marching at my heels, and then to trail feebly away, having done nothing — no, that was impossible. The crowd would laugh at me. And my whole life, every white man’s life in the East, was one long struggle not to be laughed at.

But I did not want to shoot the elephant. I watched him beating his bunch of grass against his knees, with that preoccupied grandmotherly air that elephants have. It seemed to me that it would be murder to shoot him. At that age I was not squeamish about killing animals, but I had never shot an elephant and never wanted to. (Somehow it always seems worse to kill a large animal.) Besides, there was the beast’s owner to be considered. Alive, the elephant was worth at least a hundred pounds; dead, he would only be worth the value of his tusks, five pounds, possibly. But I had got to act quickly. I turned to some experienced-

It was perfectly clear to me what I ought to do. I ought to walk up to within, say, twenty-

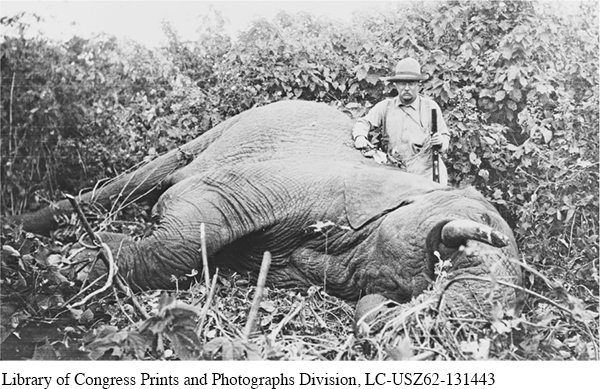

seeing connections

Teddy Roosevelt was arguably the most aggressive imperialist in American history, annexing numerous ports and territories, including the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Panama, Alaska, and Hawaii, during his time in office as either president or vice president. Roosevelt was also an avid big-

Based on what you already know or can quickly learn through research about Teddy Roosevelt’s expansionist policies and love of hunting, consider what ideas may link his imperialism and his love of hunting. How could they be related? How do those ideas help you understand more about “Shooting an Elephant”?

10 The crowd grew very still, and a deep, low, happy sigh, as of people who see the theatre curtain go up at last, breathed from innumerable throats. They were going to have their bit of fun after all. The rifle was a beautiful German thing with cross-

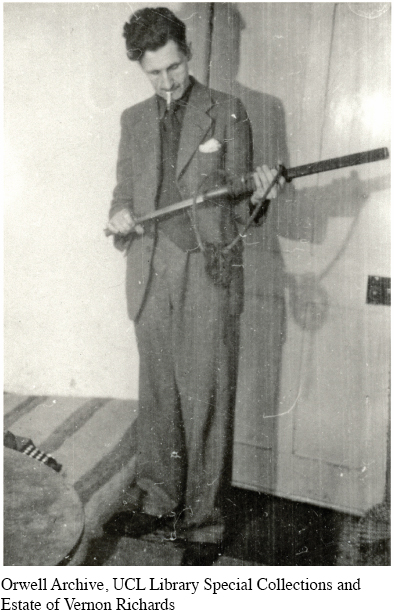

Orwell with a Burmese dah.

When I pulled the trigger I did not hear the bang or feel the kick — one never does when a shot goes home — but I heard the devilish roar of glee that went up from the crowd. In that instant, in too short a time, one would have thought, even for the bullet to get there, a mysterious, terrible change had come over the elephant. He neither stirred nor fell, but every line of his body had altered. He looked suddenly stricken, shrunken, immensely old, as though the frightful impact of the bullet had paralysed him without knocking him down. At last, after what seemed a long time — it might have been five seconds, I dare say — he sagged flabbily to his knees. His mouth slobbered. An enormous senility seemed to have settled upon him. One could have imagined him thousands of years old. I fired again into the same spot. At the second shot he did not collapse but climbed with desperate slowness to his feet and stood weakly upright, with legs sagging and head drooping. I fired a third time. That was the shot that did for him. You could see the agony of it jolt his whole body and knock the last remnant of strength from his legs. But in falling he seemed for a moment to rise, for as his hind legs collapsed beneath him he seemed to tower upward like a huge rock toppling, his trunk reaching skywards like a tree. He trumpeted, for the first and only time. And then down he came, his belly towards me, with a crash that seemed to shake the ground even where I lay.

I got up. The Burmans were already racing past me across the mud. It was obvious that the elephant would never rise again, but he was not dead. He was breathing very rhythmically with long rattling gasps, his great mound of a side painfully rising and falling. His mouth was wide open — I could see far down into caverns of pale pink throat. I waited a long time for him to die, but his breathing did not weaken. Finally I fired my two remaining shots into the spot where I thought his heart must be. The thick blood welled out of him like red velvet, but still he did not die. His body did not even jerk when the shots hit him, the tortured breathing continued without a pause. He was dying, very slowly and in great agony, but in some world remote from me where not even a bullet could damage him further. I felt that I had got to put an end to that dreadful noise. It seemed dreadful to see the great beast lying there, powerless to move and yet powerless to die, and not even to be able to finish him. I sent back for my small rifle and poured shot after shot into his heart and down his throat. They seemed to make no impression. The tortured gasps continued as steadily as the ticking of a clock.

In the end I could not stand it any longer and went away. I heard later that it took him half an hour to die. Burmans were bringing dahs6 and baskets even before I left, and I was told they had stripped his body almost to the bones by the afternoon.

Afterwards, of course, there were endless discussions about the shooting of the elephant. The owner was furious, but he was only an Indian and could do nothing. Besides, legally I had done the right thing, for a mad elephant has to be killed, like a mad dog, if its owner fails to control it. Among the Europeans opinion was divided. The older men said I was right, the younger men said it was a damn shame to shoot an elephant for killing a coolie, because an elephant was worth more than any damn Coringhee7 coolie. And afterwards I was very glad that the coolie had been killed; it put me legally in the right and it gave me a sufficient pretext for shooting the elephant. I often wondered whether any of the others grasped that I had done it solely to avoid looking a fool.

Understanding and Interpreting

George Orwell was stationed in Burma and left the police force soon after his time there. What specific evidence from the text can you find that might suggest why he left the police force?

Identify the speaker’s attitude toward the inhabitants of Burma at the following three places in the text:

the first paragraph

the paragraphs just before he shoots the elephant (pars. 9–

10) the last paragraph

Then, explain his overall feelings toward the Burmese.

In paragraph 3, the speaker says that this incident gave him “a better glimpse than I had had before of the real nature of imperialism—

the real motives for which despotic governments act.” Look back at the following statements from paragraph 7 and explain what each statement reveals about the speaker’s view of the nature of imperialism: “Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd—

seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind.” “I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys.”

“He becomes a sort of hollow, posing dummy, the conventionalized figure of a sahib. For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life in trying to impress the ‘natives,’ and so in every crisis he has got to do what the ‘natives’ expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it.”

“The crowd would laugh at me. And my whole life, every white man’s life in the East, was one long struggle not to be laughed at.”

While this essay is specifically about a time when Orwell shot an elephant, it continues to be widely read and studied in classes because it has meaning and application beyond 1920s Burma. What is the central idea that Orwell is presenting in this essay about identity? Use direct evidence from the text to support your response.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Reread the second paragraph of the piece, where the speaker provides some of his feelings about imperialism. Identify the contrasting and often contradictory choices of words as he describes the Burmese and the British. What do the contradictions reveal about the speaker’s attitude toward imperialism?

This essay is told as a narrative with the speaker looking back on a significant event in his life. How does the older Orwell view his younger self, and what specific language choices reflect this tone?

Reread paragraph 11, where the speaker first shoots the elephant. What are some of the words and phrases that are used to humanize the elephant’s death and how do these details help to illustrate Orwell’s point about imperialism?

You are reading this piece in a textbook almost eighty years after it was originally published. Who do you think was Orwell’s intended audience in 1936, and what do you think he was trying to communicate to them? How successful do you think he might have been in communicating his message? Why?

Below is the last paragraph of the essay with some words underlined. Reread this paragraph, looking closely at the underlined words and the synonyms that follow in parentheses. Discuss how changing Orwell’s word choice to one of the words in parentheses would affect the meaning of the sentences containing these words and the passage as a whole.

Afterwards, of course, there were endless (interminable/incessant) discussions about the shooting of the elephant. The owner was furious, but he was only an Indian and could do nothing. Besides, legally (justly/legitimately) I had done the right thing, for a mad elephant has to be killed (executed/put down/slaughtered), like a mad dog, if its owner fails to control it. Among the Europeans opinion was divided. The older men said I was right, the younger men said it was a damn shame to shoot an elephant for killing a coolie, because an elephant was worth more than any damn Coringhee coolie. And afterwards I was very glad (cheerful/content/pleased) that the coolie had been killed; it put me legally in the right and it gave me a sufficient (ample/acceptable) pretext (alibi/excuse/pretense) for shooting the elephant. I often wondered whether any of the others grasped that I had done it solely to avoid looking a fool (buffoon/idiot/bonehead).

Topics for Composing

Exposition

Many of the reasons that the speaker gives for shooting the elephant are implied rather than directly stated. In an essay, identify and explain the most significant reasons for the shooting, and conclude with an evaluation of which one was likely the primary motivation.Exposition

How aware is the speaker of his own role in the worst elements of colonialism? Write an essay in which you respond to that question by drawing solely on the evidence that Orwell presents within the text.Argument

At the end of the piece, Orwell writes, “The owner was furious, but he was only an Indian and could do nothing.” Write two letters about this situation:The first letter should be from the point of view of the elephant’s owner, trying to convince the district administrator of Burma to compensate you for the loss of your elephant. Imagine that upon receiving this letter, the district administrator demands an explanation from Orwell.

The second letter should be written as if you were Orwell responding to the district administrator. Be sure to explain why the shooting of the elephant was justified, and address the points contained within the letter from the elephant’s owner. Your letters should be limited only to the events presented in the piece, but you should use whatever persuasive techniques you think would be useful in convincing your audience.

Page 123Research

How can psychological principles help us understand the factors that may have contributed to Orwell’s decision to shoot the elephant, even though he did not want to? Research a relevant psychological study or psychological perspective, explain the experiment and its findings to your readers, and then describe how the findings help explain the psychological factors at work in “Shooting an Elephant.” You might begin by looking into the Stanford Prison Experiment (Philip Zimbardo), the Asch Conformity Experiments (Solomon Asch), the Good Samaritan Study (John Darley and C. Daniel Batson), the Milgram Experiment (Stanley Milgram), or the Bystander Effect (John Darley and Bibb Latané). Feel free to uncover additional studies that interest you.Research

While the speaker in Orwell’s piece regularly uses the word “imperialism” to describe the British activities in Burma because it refers to the expansion of an “empire,” another related and more general term is “colonialism,” which applies to any country’s conquering and exploiting the resources of another country. Research present-day Myanmar, or another country that was colonized, and identify the effects colonialism had. Narrative

At the moment the speaker decides to shoot the elephant, he states, “[I]t is the condition of his rule that [the white man] shall spend his life in trying to impress the ‘natives,’ and so in every crisis he has got to do what the ‘natives’ expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it” (par. 7). Write a story about a time when you had to wear a metaphorical mask (do something that someone expected you to do). What caused you to wear the mask? Did your face “grow to fit it,” as the speaker of “Shooting an Elephant” suggests, or were you able to take the mask off and become yourself again?Multimodal

Make a short film—or draw a storyboard of scenes— in which you reenact paragraph 7 from “Shooting an Elephant.” Then, write a brief explanation about why you chose to film or draw it the way you did. How did the music, camera angles, lighting, acting choices, and so on that you used relate to the specific words that Orwell used? Discussion or performance

Hold a mock trial to debate the speaker’s actions. There should be a prosecutor who is trying to convict the speaker of property damage, a defense attorney who is trying to justify the speaker’s actions, a judge, and a jury to determine guilt or innocence. Be sure that all of the evidence you consider comes directly from the text itself and any relevant research you conduct on the time period and location.Creative

George Orwell is not a hero in this piece. He doesn’t take a principled stand and refuse to shoot the elephant, nor does he rebel against an imperial system that he seems to disapprove of and yet participates in. Write a new ending for the essay in which Orwell decides not to shoot the elephant. Continue to use the first person narration, try to mimic Orwell’s style as closely as possible, and include the reasoning behind his decision. Be sure to consider how the last paragraph would change significantly as a result of this different decision. Include a reflection that explains what changed and why.