5.4

The Devils Thumb

Jon Krakauer

Writer Jon Krakauer (b. 1954) has been a risk taker and adventurer most of his life. The author of the highly acclaimed account of a disastrous attempt to climb Mount Everest, Into Thin Air, Krakauer spent much of his own youth climbing various mountains around the world, the accounts of which were collected in Eiger Dreams: Ventures among Men and Mountains, from which this narrative is taken. Krakauer is also the author of Into the Wild, the true story of the life and death of Chris McCandless, a young man who tried to live on his own in the backcountry of Alaska, and died as a result. Rather than simply celebrating the accomplishments of adventurers, Krakauer examines the risks and contradictions of trying to find yourself by going toe-

By the time I reached the interstate I was having trouble keeping my eyes open. I’d been okay on the twisting two-

That afternoon, after nine hours of humping 2 X 10s and pounding recalcitrant nails, I’d told my boss I was quitting: “No, not in a couple of weeks, Steve; right now was more like what I had in mind.” It took me three more hours to clear my tools and other belongings out of the rust-

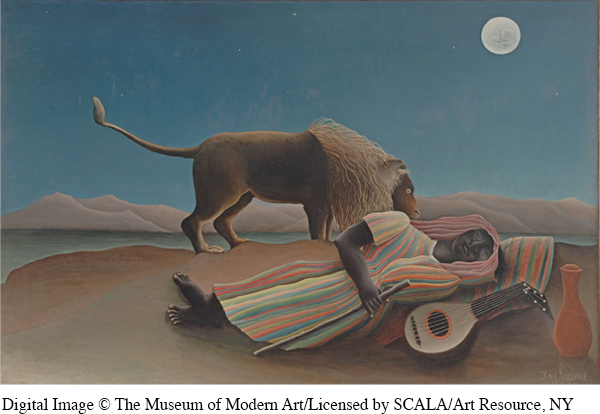

At 1 a.m., thirty miles east of Rawlins, the strain of the day caught up to me. The euphoria that had flowed so freely in the wake of my quick escape gave way to overpowering fatigue; suddenly I felt tired to the bone. The highway stretched straight and empty to the horizon and beyond. Outside the car the night air was cold, and the stark Wyoming plains glowed in the moonlight like Rousseau’s painting of the sleeping gypsy. I wanted very badly just then to be that gypsy, conked out on my back beneath the stars. I shut my eyes — just for a second, but it was a second of bliss. It seemed to revive me, if only briefly. The Pontiac, a sturdy behemoth from the Eisenhower years, floated down the road on its long-

A few minutes later I let my eyelids fall again. I’m not sure how long I nodded off this time — it might have been for five seconds, it might have been for thirty — but when I awoke it was to the rude sensation of the Pontiac bucking violently along the dirt shoulder at seventy miles per hour. By all rights, the car should have sailed off into the rabbitbrush and rolled. The rear wheels fishtailed wildly six or seven times, but I eventually managed to guide the unruly machine back onto the pavement without so much as blowing a tire, and let it coast gradually to a stop. I loosened my death grip on the wheel, took several deep breaths to quiet the pounding in my chest, then slipped the shifter back into drive and continued down the highway.

5 Pulling over to sleep would have been the sensible thing to do, but I was on my way to Alaska to change my life, and patience was a concept well beyond my twenty-

Sixteen months earlier I’d graduated from college with little distinction and even less in the way of marketable skills. In the interim an off-

Late one evening I was mulling all this over on a barstool at Tom’s, picking unhappily at my existential scabs, when an idea came to me, a scheme for righting what was wrong in my life. It was wonderfully uncomplicated, and the more I thought about it, the better the plan sounded. By the bottom of the pitcher its merits seemed unassailable. The plan consisted, in its entirety, of climbing a mountain in Alaska called the Devils Thumb.

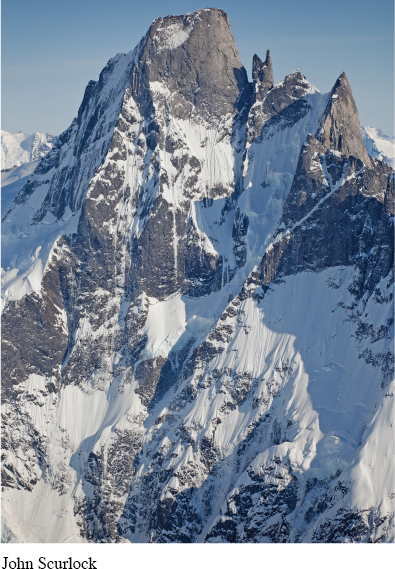

The Devils Thumb is a prong of exfoliated diorite that presents an imposing profile from any point of the compass, but especially so from the north: its great north wall, which had never been climbed, rises sheer and clean for six thousand vertical feet from the glacier at its base. Twice the height of Yosemite’s El Capitan, the north face of the Thumb is one of the biggest granitic walls on the continent; it may well be one of the biggest in the world. I would go to Alaska, ski across the Stikine Icecap to the Devils Thumb, and make the first ascent of its notorious nordwand. It seemed, midway through the second pitcher, like a particularly good idea to do all of this solo.

Henri Rousseau, The Sleeping Gypsy, 1897. Oil on canvas.

Writing these words more than a dozen years later, it’s no longer entirely clear just how I thought soloing the Devils Thumb would transform my life. It had something to do with the fact that climbing was the first and only thing I’d ever been good at. My reasoning, such as it was, was fueled by the scattershot passions of youth, and a literary diet overly rich in the works of Nietzsche, Kerouac, and John Menlove Edwards — the latter a deeply troubled writer/psychiatrist who, before putting an end to his life with a cyanide capsule in 1958, had been one of the preeminent British rock climbers of the day.

10 Dr. Edwards regarded climbing as a “psycho-

So, as you would imagine, I grew up exuberant in body but with a nervy, craving mind: It was wanting something more, something tangible. It sought for reality intensely, always if it were not there . . .

But you see at once what I do. I climb.

To one enamored of this sort of prose, the Thumb beckoned like a beacon. My belief in the plan became unshakeable. I was dimly aware that I might be getting in over my head, but if I could somehow get to the top of the Devils Thumb, I was convinced, everything that followed would turn out all right. And thus did I push the accelerator a little closer to the floor and, buoyed by the jolt of adrenaline that followed the Pontiac’s brush with destruction, speed west into the night.

. . .

You can’t actually get very close to the Devils Thumb by car. The peak stands in the Boundary Ranges on the Alaska–

Back in Boulder, without exception, every person with whom I’d shared my plans about the Thumb had been blunt and to the point: I’d been smoking too much pot, they said; it was a monumentally bad idea. I was grossly overestimating my abilities as a climber, I’d never be able to hack a month completely by myself, I would fall into a crevasse and die.

The residents of Petersburg reacted differently. Being Alaskans, they were accustomed to people with screwball ideas; a sizeable percentage of the state’s population, after all, was sitting on half-

15 In any case, one of the appealing things about climbing the Thumb — and one of the appealing things about the sport of mountain climbing in general — was that it didn’t matter a rat’s ass what anyone else thought. Getting the scheme off the ground didn’t hinge on winning the approval of some personnel director, admissions committee, licensing board, or panel of stern-

Petersburg sits on an island, the Devils Thumb rises from the mainland. To get myself to the foot of the Thumb it was first necessary to cross twenty-

Bart and Benjamin were ponytailed constituents of a Woodstock Nation tree-

The Devils Thumb pokes up out of the Stikine Icecap, an immense, labyrinthine network of glaciers that hugs the crest of the Alaskan panhandle like an octopus, with myriad tentacles that snake down, down to the sea from the craggy uplands along the Canadian frontier. In putting ashore at Thomas Bay I was gambling that one of these frozen arms, the Baird Glacier, would lead me safely to the bottom of the Thumb, thirty miles distant.

An hour of gravel beach led to the tortured blue tongue of the Baird. A logger in Petersburg had suggested I keep an eye out for grizzlies along this stretch of shore. “Them bears over there is just waking up this time of year,” he smiled. “Tend to be kinda cantankerous after not eatin’ all winter. But you keep your gun handy, you shouldn’t have no problem.” Problem was, I didn’t have a gun. As it turned out, my only encounter with hostile wildlife involved a flock of gulls who dive-

20 After three or four miles I came to the snowline, where I exchanged crampons for skis. Putting the boards on my feet cut fifteen pounds from the awful load on my back and made the going much faster besides. But now that the ice was covered with snow, many of the glacier’s crevasses were hidden, making solitary travel extremely dangerous.

In Seattle, anticipating this hazard, I’d stopped at a hardware store and purchased a pair of stout aluminum curtain rods, each ten feet long. Upon reaching the snowline, I lashed the rods together at right angles, then strapped the arrangement to the hip belt on my backpack so the poles extended horizontally over the snow. Staggering slowly up the glacier with my overloaded backpack, bearing the queer tin cross, I felt like some kind of strange Penitente. Were I to break through the veneer of snow over a hidden crevasse, though, the curtain rods would — I hoped mightily — span the slot and keep me from dropping into the chilly bowels or the Baird.

The first climbers to venture onto the Stikine Icecap were Bestor Robinson and Fritz Wiessner, the legendary German-

In the ensuing decades three other teams also made it to the top of the Thumb, but all steered clear of the big north face. Reading accounts of these expeditions, I had wondered why none of them had approached the peak by what appeared, from the map at least, to be the easiest and most logical route, the Baird. I wondered a little less after coming across an article by Beckey in which the distinguished mountaineer cautioned, “Long, steep icefalls block the route from the Baird Glacier to the icecap near Devils Thumb,” but after studying aerial photographs I decided that Beckey was mistaken, that the icefalls weren’t so big or so bad. The Baird, I was certain, really was the best way to reach the mountain.

For two days I slogged steadily up the glacier without incident, congratulating myself for discovering such a clever path to the Thumb. On the third day, I arrived beneath the Stikine Icecap proper, where the long arm of the Baird joins the main body of ice. Here, the glacier spills abruptly over the edge of a high plateau, dropping seaward through the gap between two peaks in a phantasmagoria of shattered ice. Seeing the icefall in the flesh left a different impression than the photos had. As I stared at the tumult from a mile away, for the first time since leaving Colorado the thought crossed my mind that maybe this Devils Thumb trip wasn’t the best idea I’d ever had.

25 The icefall was a maze of crevasses and teetering seracs1. From afar it brought to mind a bad train wreck, as if scores of ghostly white boxcars had derailed at the lip of the icecap and tumbled down the slope willy-

In my impetuosity, I decided to carry on anyway. For the better part of the day I groped blindly through the labyrinth in the whiteout, retracing my steps from one dead end to another. Time after time I’d think I’d found a way out, only to wind up in a deep blue cul de sac, or stranded atop a detached pillar of ice. My efforts were lent a sense of urgency by the noises emanating underfoot. A madrigal of cracks and sharp reports — the sort of protests a large fir limb makes when it’s slowly bent to the breaking point — served as a reminder that it is the nature of glaciers to move, the habit of seracs to topple.

As much as I feared being flattened by a wall of collapsing ice, I was even more afraid of falling into a crevasse, a fear that intensified when I put a foot through a snow bridge over a slot so deep I couldn’t see the bottom of it. A little later I broke through another bridge to my waist; the poles kept me out of the hundred-

Night had nearly fallen by the time I emerged from the top of the serac slope onto the empty, wind-

Although my plan to climb the Devils Thumb wasn’t fully hatched until the spring of 1977, the mountain had been lurking in the recesses of my mind for about fifteen years — since April 12, 1962, to be exact. The occasion was my eighth birthday. When it came time to open birthday presents, my parents announced that they were offering me a choice of gifts: According to my wishes, they would either escort me to the new Seattle World’s Fair to ride the Monorail and see the Space Needle, or give me an introductory taste of mountain climbing by taking me up the third highest peak in Oregon, a long-

30 To prepare me for the rigors of the ascent, my father handed over a copy of Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, the leading how-

Which is not to suggest that my parents and I conquered the mighty volcano: From the pages and pages of perilous situations depicted in Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, I had concluded that climbing was a life-

Perversely, after the South Sister debacle my interest in climbing only intensified. I resumed my obsessive studies of Mountaineering. There was something about the scariness of the activities portrayed in those pages that just wouldn’t leave me alone. In addition to the scores of line drawings — most of them cartoons of a little man in a jaunty Tyrolean cap — employed to illustrate arcana like the boot-

A view of the still-

From the first time I saw it, the picture — a portrait of the Thumb’s north wall — held an almost pornographic fascination for me. On hundreds — no, make that thousands — of occasions over the decade and a half that followed I took my copy of Mountaineering down from the shelf, opened it to page 147, and quietly stared. How would it feel, I wondered over and over, to be on that thumbnail-

I had planned on spending between three weeks and a month on the Stikine Icecap. Not relishing the prospect of carrying a four-

35 On May 6 I set up a base camp on the Icecap just northeast of the Thumb and waited for the airdrop. For the next four days it snowed, nixing any chance for a flight. Too terrified of crevasses to wander far from camp, I occasionally went out for a short ski to kill time, but mostly I lay silently in the tent — the ceiling was too low to sit upright — with my thoughts, fighting a rising chorus of doubts.

As the days passed, I grew increasingly anxious. I had no radio, nor any other means of communicating with the outside world. It had been many years since anyone had visited this part of the Stikine Icecap, and many more would likely pass before anyone did so again. I was nearly out of stove fuel, and down to a single chunk of cheese, my last package of ramen noodles, and half a box of Cocoa Puffs. This, I figured, could sustain me for three or four more days if need be, but then what would I do? It would only take two days to ski back down the Baird to Thomas Bay, but then a week or more might easily pass before a fisherman happened by who could give me a lift back to Petersburg (the Hodads with whom I’d ridden over were camped fifteen miles down the impassable, headland-

When I went to bed on the evening of May 10 it was still snowing and blowing hard. I was going back and forth on whether to head for the coast in the morning or stick it out on the icecap, gambling that the pilot would show before I starved or died of thirst, when, just for a moment, I heard a faint whine, like a mosquito. I tore open the tent door. Most of the clouds had lifted, but there was no airplane in sight. The whine returned, louder this time. Then I saw it: a tiny red-

A few minutes later the plane passed directly overhead. The pilot, however, was unaccustomed to glacier flying and he’d badly misjudged the scale of the terrain. Worried about winding up too low and getting nailed by unexpected turbulence, he flew a good thousand feet above me — believing all the while he was just off the deck — and never saw my tent in the flat evening light. My waving and screaming were to no avail; from that altitude l was indistinguishable from a pile of rocks. For the next hour he circled the icecap, scanning its barren contours without success. But the pilot, to his credit, appreciated the gravity of my predicament and didn’t give up. Frantic, I tied my sleeping bag to the end of one of the crevasse poles and waved it for all I was worth. When the plane banked sharply and began to fly straight at me, I felt tears of joy well in my eyes.

The pilot buzzed my tent three times in quick succession, dropping two boxes on each pass, then the airplane disappeared over a ridge and I was alone. As silence again settled over the glacier I felt abandoned, vulnerable, lost. I realized that I was sobbing. Embarrassed, I halted the blubbering by screaming obscenities until I grew hoarse.

40 I awoke early on May 11 to clear skies and the relatively warm temperature of twenty degrees Fahrenheit. Startled by the good weather, mentally unprepared to commence the actual climb, I hurriedly packed up a rucksack nonetheless, and began skiing toward the base of the Thumb. Two previous Alaskan expeditions had taught me that, ready or not, you simply can’t afford to waste a day of perfect weather if you expect to get up anything.

A small hanging glacier extends out from the lip of the icecap, leading up and across the north face of the Thumb like a catwalk. My plan was to follow this catwalk to a prominent rock prow in the center of the wall, and thereby execute an end run around the ugly, avalanche-

The catwalk turned out to be a series of fifty-

The rock, exhibiting a dearth of holds and coated with six inches of crumbly rime, did not look promising, but just left of the main prow was an inside corner — what climbers call an open book — glazed with frozen melt water. This ribbon of ice led straight up for two or three hundred feet, and if the ice proved substantial enough to support the picks of my ice axes, the line might go. I hacked out a small platform in the snow slope, the last flat ground I expected to feel underfoot for some time, and stopped to eat a candy bar and collect my thoughts. Fifteen minutes later I shouldered my pack and inched over to the bottom of the corner. Gingerly, I swung my right axe into the two-

The climbing was steep and spectacular, so exposed it made my head spin. Beneath my boot soles, the wall fell away for three thousand feet to the dirty, avalanche-

45 The higher I climbed, the more comfortable I became. All that held me to the mountainside, all that held me to the world, were six thin spikes of chrome-

By and by, your attention becomes so intensely focused that you no longer notice the raw knuckles, the cramping thighs, the strain of maintaining nonstop concentration. A trance-

At such moments, something like happiness actually stirs in your chest, but it isn’t the sort of emotion you want to lean on very hard. In solo climbing, the whole enterprise is held together with little more than chutzpa, not the most reliable adhesive. Late in the day on the north face of the Thumb, I felt the glue disintegrate with a single swing of an ice axe.

I’d gained nearly seven hundred feet of altitude since stepping off the hanging glacier, all of it on crampon front-

I tried left, then right, but kept striking rock. The frost feathers holding me up, it became apparent, were maybe five inches thick and had the structural integrity of stale cornbread. Below was thirty-

50 Awkwardly, stiff with fear, I started working my way back down. The rime gradually thickened, and after descending about eighty feet I got back on reasonably solid ground. I stopped for a long time to let my nerves settle, then leaned back from my tools and stared up at the face above, searching for a hint of solid ice, for some variation in the underlying rock strata, for anything that would allow passage over the frosted slabs. I looked until my neck ached, but nothing appeared. The climb was over. The only place to go was down.

Heavy snow and incessant winds kept me inside the tent for most of the next three days. The hours passed slowly. In the attempt to hurry them along I chain-

Near the end of Common Prayer, one of Didion’s characters says to another, “You don’t get any real points for staying here, Charlotte.” Charlotte replies, “I can’t seem to tell what you do get real points for, so I guess I’ll stick around here for awhile.”

When I ran out of things to read, I was reduced to studying the ripstop pattern woven into the tent ceiling. This I did for hours on end, flat on my back, while engaging in an extended and very heated self-

By the third afternoon of the storm I couldn’t stand it any longer: the lumps of frozen snow poking me in the back, the clammy nylon walls brushing against my face, the incredible smell drifting up from the depths of my sleeping bag. I pawed through the mess at my feet until I located a small green stuff sack, in which there was a metal film can containing the makings of what I’d hoped would be a sort of victory cigar. I’d intended to save it for my return from the summit, but what the hey, it wasn’t looking like I’d be visiting the top any time soon. I poured most of the can’s contents into a leaf of cigarette paper, rolled it into a crooked, sorry looking joint, and promptly smoked it down to the roach.

55 The reefer, of course, only made the tent seem even more cramped, more suffocating, more impossible to bear. It also made me terribly hungry. I decided a little oatmeal would put things right. Making it, however, was a long, ridiculously involved process: a potful of snow had to be gathered outside in the tempest, the stove assembled and lit, the oatmeal and sugar located, the remnants of yesterday’s dinner scraped from my bowl. I’d gotten the stove going and was melting the snow when I smelled something burning. A thorough check of the stove and its environs revealed nothing. Mystified, I was ready to chalk it up to my chemically enhanced imagination when I heard something crackle directly behind me.

I whirled around in time to see a bag of garbage, into which I’d tossed the match I’d used to light the stove, flare up into a conflagration. Beating on the fire with my hands, I had it out in a few seconds, but not before a large section of the tent’s inner wall vaporized before my eyes. The tent’s built-

The fire sent me into a funk that no drug known to man could have alleviated. By the time I’d finished cooking the oatmeal my mind was made up: the moment the storm was over, I was breaking camp and booking for Thomas Bay.

Twenty-

The day had begun well enough. When I emerged from the tent, clouds still clung to the ridge tops but the wind was down and the icecap was speckled with sunbreaks. A patch of sunlight, almost blinding in its brilliance, slid lazily over the camp. I put down a foam sleeping mat and sprawled on the glacier in my long johns. Wallowing in the radiant heat, I felt the gratitude of a prisoner whose sentence has just been commuted.

60 As I lay there, a narrow chimney that curved up the east half of the Thumb’s north face, well to the left of the route I’d tried before the storm, caught my eye. I twisted a telephoto lens onto my camera. Through it I could make out a smear of shiny grey ice — solid, trustworthy, hard-

The ice in the chimney did in fact prove to be continuous, but it was very, very thin — just a gossamer film of verglas. Additionally, the cleft was a natural funnel for any debris that happened to slough off the wall; as I scratched my way up the chimney I was hosed by a continuous stream of powder snow, ice chips, and small stones. One hundred twenty feet up the groove the last remnants of my composure flaked away like old plaster, and I turned around.

Instead of descending all the way to base camp, I decided to spend the night in the ’schrund beneath the chimney, on the off chance that my head would be more together the next morning. The fair skies that had ushered in the day, however, turned out to be but a momentary lull in a five-

The descent was terrifying. Between the clouds, the ground blizzard, and the flat, fading light, I couldn’t tell snow from sky, nor whether a slope went up or down. I worried, with ample reason, that I might step blindly off the top of a serac and end up at the bottom of the Witches Cauldron, a half-

I dug a shallow hole, wrapped myself in the bivvy bag, and sat on my pack in the swirling snow. Drifts piled up around me. My feet became numb. A damp chill crept down my chest from the base of my neck, where spindrift had gotten inside my parka and soaked my shirt. If only I had a cigarette, I thought, a single cigarette, l could summon the strength of character to put a good face on this [messed]-up situation, on the whole [messed]-up trip. “If we had some ham, we could have ham and eggs, if we had some eggs.” I remembered my friend Nate uttering that line in a similar storm, two years before, high on another Alaskan peak, the Mooses Tooth. It had struck me as hilarious at the time; I’d actually laughed out loud. Recalling the line now, it no longer seemed funny. I pulled the bivvy sack tighter around my shoulders. The wind ripped at my back. Beyond shame, I cradled my head in my arms and embarked on an orgy of self-

65 I knew that people sometimes died climbing mountains. But at the age of twenty-

At sunset the wind died and the ceiling lifted a hundred fifty feet off the glacier, enabling me to locate base camp. I made it back to the tent intact, but it was no longer possible to ignore the fact that the Thumb had made hash of my plans. I was forced to acknowledge that volition alone, however powerful, was not going to get me up the north wall. I saw, finally, that nothing was.

There still existed an opportunity for salvaging the expedition, however. A week earlier I’d skied over to the southeast side of the mountain to take a look at the route Fred Beckey had pioneered in 1946 — the route by which I’d intended to descend the peak after climbing the north wall. During that reconnaissance I’d noticed an obvious unclimbed line to the left of the Beckey route — a patchy network of ice angling across the southeast face — that struck me as a relatively easy way to achieve the summit. At the time, I’d considered this route unworthy of my attentions. Now, on the rebound from my calamitous entanglement with the nordwand, I was prepared to lower my sights.

A view of the eastern route up the Devils Thumb, the route that Krakauer ultimately took.

On the afternoon of May 15, when the blizzard finally petered out, I returned to the southeast face and climbed to the top of a slender ridge that abutted the upper peak like a flying buttress on a gothic cathedral. I decided to spend the night there, on the airy, knife-

That night I had troubled dreams, of cops and vampires and a gangland-

70 I carried no rope, no tent or bivouac gear, no hardware save my ice axes. My plan was to go ultralight and ultrafast, to hit the summit and make it back down before the weather turned. Pushing myself, continually out of breath, I scurried up and to the left across small snowfields linked by narrow runnels of verglas and short rock bands. The climbing was almost fun — the rock was covered with large, in-

seeing connections

In 1993, Krakauer wrote an article for Outside magazine about Chris McCandless, a twenty-

In 1977, when I was 23—

When I decided to go to Alaska that April, I was an angst-

As a young man, I was unlike Chris McCandless in many important respects—

The fact that I survived my Alaskan adventure and McCandless did not survive his was largely a matter of chance; had I died on the Stikine Icecap in 1977 people would have been quick to say of me, as they now say of him, that I had a death wish. Fifteen years after the event, I now recognize that I suffered from hubris, perhaps, and a monstrous innocence, certainly, but I wasn’t suicidal.

Read the excerpt below from the screenplay of Into the Wild, and comment on whether McCandless and Krakauer do in fact share a similar “agitation of the soul.” Compare Krakauer’s motivations with those ascribed to McCandless in the following scene from the movie, in which he talks about his trip to Alaska with his friend Wayne Westberg.

CHRIS

I’m thinking about going to Alaska.

WAYNE

Alaska, Alaska? Or city Alaska? The city Alaska does have markets.

CHRIS

(with a drunken, excited energy)

No, Alaska, Alaska. I want to be all the way out there. On my own. No map. No watch. No axe. Just out there. Big mountains, rivers, sky. Game. Just be out there in it. In the wild.

WAYNE

In the wild.

CHRIS

Yeah. Maybe write a book about my travels. About getting out of this sick society.

WAYNE

(coughing)

Society, right.

CHRIS

Because you know what I don’t understand? I don’t understand why, why people are so bad to each other, so often. It just doesn’t make any sense to me. Judgment. Control. All that.

WAYNE

Who “people” we talking about?

CHRIS

You know, parents and hypocrites. Politicians and [jerks].

A frame from the movie Into the Wild showing Chris McCandless leaving the road behind and entering the Alaskan wilderness.

How is this setting and situation similar to that of Krakauer in Alaska? What effect is created by the overhead point of view of this shot?

A frame from the movie Into the Wild showing Chris McCandless burning his wallet and heading out into the Arizona desert. In the movie, Chris’s sister comments: “Chris began to see ‘careers’ as a diseased invention of the twentieth century and to resent money and the useless priority people made of it in their lives.”

Do you think a young Krakauer would have agreed with this sentiment?

In what seemed like no time (I didn’t have a watch on the trip) I was on the distinctive final ice field. By now the sky was completely overcast. It looked easier to keep angling to the left, but quicker to go straight for the top. Paranoid about being caught by a storm high on the peak without any kind of shelter, I opted for the direct route. The ice steepened, then steepened some more, and as it did so it grew thin. I swung my left ice axe and struck rock. I aimed for another spot, and once again it glanced off unyielding diorite with a dull, sickening clank. And again, and again: It was a reprise of my first attempt on the north face. Looking between my legs, I stole a glance at the glacier, more than two thousand feet below. My stomach churned. I felt my poise slipping way like smoke in the wind.

Forty-

The insubstantial frost feathers ensured that those last twenty feet remained hard, scary, onerous. But then, suddenly, there was no place higher to go. It wasn’t possible, I couldn’t believe it. I felt my cracked lips stretch into a huge, painful grin. I was on top of the Devils Thumb.

Fittingly, the summit was a surreal, malevolent place, an improbably slender fan of rock and rime no wider than a filing cabinet. It did not encourage loitering. As I straddled the highest point, the north face fell away beneath my left boot for six thousand feet; beneath my right boot the south face dropped off for twenty-

75 Five days later I was camped in the rain beside the sea, marveling at the sight of moss, willows, mosquitoes. Two days after that, a small skiff motored into Thomas Bay and pulled up on the beach not far from my tent. The man driving the boat introduced himself as Jim Freeman, a timber faller from Petersburg. It was his day off, he said, and he’d made the trip to show his family the glacier, and to look for bears. He asked me if I’d “been huntin’, or what?”

“No,” I replied sheepishly. “Actually, I just climbed the Devils Thumb. I’ve been over here twenty days.”

Freeman kept fiddling with a cleat on the boat, and didn’t say anything for a while. Then he looked at me real hard and spat, “You wouldn’t be givin’ me double talk now, wouldja, friend?” Taken aback, I stammered out a denial. Freeman, it was obvious, didn’t believe me for a minute. Nor did he seem wild about my snarled shoulder-

The water was choppy, and the ride across Frederick Sound took two hours. The more we talked, the more Freeman warmed up. He still didn’t believe I’d climbed the Thumb, but by the time he steered the skiff into Wrangell Narrows he pretended to. When we got off the boat, he insisted on buying me a cheeseburger. That night he even let me sleep in a derelict step-

Taking the western route, climber Mikey Schaefer ascends the Cat Ear Spire on his way to the top of the Devils Thumb.

I lay down in the rear of the old truck for a while but couldn’t sleep, so I got up and walked to a bar called Kito’s Kave. The euphoria, the overwhelming sense of relief, that had initially accompanied my return to Petersburg faded, and an unexpected melancholy took its place. The people I chatted with in Kito’s didn’t seem to doubt that I’d been to the top of the Thumb, they just didn’t much care. As the night wore on the place emptied except for me and an Indian at a back table. I drank alone, putting quarters in the jukebox, playing the same five songs over and over, until the barmaid yelled angrily, “Hey! Give it a [. . .] rest, kid! If I hear ‘Fifty Ways to Lose Your Lover’ one more time, I’m gonna be the one who loses it.” I mumbled an apology, quickly headed for the door, and lurched back to Freeman’s step-

80 It is easy, when you are young, to believe that what you desire is no less than what you deserve, to assume that if you want something badly enough it is your God-

Climbing the Devils Thumb, however, had nudged me a little further away from the obdurate innocence of childhood. It taught me something about what mountains can and can’t do, about the limits of dreams. I didn’t recognize that at the time, of course, but I’m grateful for it now.

Understanding and Interpreting

Much of Krakauer’s motivation to successfully climb the mountain seems to come from his need to impress others. Locate at least two places in the text where this appears to be true and explain how those passages illustrate this aspect of Krakauer.

There are several places in the narrative in which Krakauer demonstrates an appalling lack of planning or forethought, and there are others where he does successfully make plans. Identify examples of both and explain which trait is more prevalent in the narrative.

Make an argumentative claim about Krakauer’s decision-

making and reasoning skills. Then, support that claim with direct evidence from the text. Trace the numerous setbacks Krakauer faces in trying to scale the Devils Thumb. Select one setback, and explain what his response to that setback reveals about his character.

What purpose does the history lesson about the previous climbs and attempts on the Devils Thumb (pars. 22 and 23) serve in the narrative? Why does Krakauer include it?

What role has the Devils Thumb played in Krakauer’s imagination since he started looking at it in the book he received when he was eight? How does this role influence his later decisions?

Reread paragraph 46. What effect does the physical act of climbing have on Krakauer?

What is the connection that the reader is expected to draw between Krakauer and the character in the Joan Didion novel (par. 52)?

In terms of Krakauer’s own personal development, there is probably no other passage from the narrative that is as important as his statement, “At the time, I’d considered this route unworthy of my attentions. Now . . . I was prepared to lower my sights” (par. 67). In what way does this revelation signal a significant change in Krakauer?

To what extent is Krakauer satisfied or disappointed with his climb? What evidence from the text supports your position?

Krakauer writes at the end that climbing the Devils Thumb taught him “something about what mountains can and can’t do, about the limits of dreams” (par. 81). What is this “something” that he learned?

Analyzing Language, Structure, and Style

What is the effect that Krakauer achieves by starting his narrative with his drive up to Alaska?

Krakauer includes two flashbacks in his narrative—

in paragraphs 6– 7 and then paragraphs 29– 33. Analyze those two structural choices, examining why each flashback is placed where it is, and what effect it has on the reader’s knowledge about and impressions of Krakauer. It is clear that Krakauer is writing this narrative as an older man looking back on an event that happened to him when he was younger (“Writing these words more than a dozen years later. . . .” [par. 9]). How would you describe the tone Krakauer takes toward his younger self? What specific words or phrases communicate this tone? How does this tone help Krakauer to create a theme of the narrative?

In paragraphs 13 and 14, Krakauer constructs a contrast between Coloradans and Alaskans in their attitudes toward his plans to climb the Devils Thumb. What is the purpose of this contrast?

Reread paragraph 18, paying attention to the imagery Krakauer uses. How does it help illustrate the conflict Krakauer is facing?

Reread the following lines from the essay and explain what the word choice reveals about Krakauer:

“I’d never heard of hubris” (par. 65).

“and the mountain would be mine” (par. 72)

“my head swimming with visions of glory and redemption” (par. 65)

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

In the last paragraph, Krakauer says that this experience moved him “a little further away from the obdurate innocence of childhood.” The word “obdurate” means “stubborn,” and it often has a negative connotation. Tell a story about a time when you, perhaps unwillingly, had to give up some of the innocence of your own childhood. In what ways was your childhood innocence “obdurate” like Krakauer’s?

You may recall reading about the Evil Queen from the Snow White story at the beginning of this chapter, and about the two different ways that people define their identities: as they see themselves, and as others see them. In this narrative, does Krakauer seem more concerned about how other people view him and his climb or how he views himself? Use direct evidence from the text to support your argument.

There are many places where Krakauer faces serious peril in his climb. Should he have stopped or gone forward? What evidence from the text, and your own reasoning, can you use to support your argument?

Krakauer writes, “Because I wanted to climb the mountain so badly, because I had thought about the Thumb so intensely for so long, it seemed beyond the realm of possibility that some minor obstacle like the weather or crevasses or rime-

covered rock might ultimately thwart my will” (par. 65). In other words, because he thought about it so much, his success should automatically happen. This is an example of what is often referred to as “magical thinking,” belief that thinking about something can make it happen. A common example of magical thinking is when viewers of a sporting event think they can influence the outcome of the game by what they wear or the foods they eat during a game. Research the topic of magical thinking, identify and explain other instances in the narrative where Krakauer engages in this process, and connect one of these instances to another example from outside the text, perhaps even from your own life. In paragraph 65, Krakauer admits, “I knew that people sometimes died climbing mountains. But at the age of twenty-

three personal mortality — the idea of my own death — was still largely out of my conceptual grasp. . . .” Here, Krakauer addresses a significant concern that has been the subject of a lot of research: adolescents often take part in risky behaviors that can lead to injury and death because of a number of factors. Research one or more factors — including brain development — that can lead adolescents to be unconcerned about “personal mortality” and apply that factor to Krakauer’s actions in this narrative. Look over these famous lines from Ralph Waldo Emerson, an American writer who popularized what was called the Transcendentalist Movement during the middle of the nineteenth century. Transcendentalists believed in the beauty of nature, the power of the individual, and the importance of freedom. Based upon your reading of his narrative, explain why Krakauer might agree or disagree with each and describe your own thoughts about the lines.

“Do not be too timid and squeamish about your actions. All life is an experiment. The more experiments you make the better.”

“There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better for worse as his portion.”

“Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string. Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events. Great men have always done so.”

“Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist.”