Ambition: Why Some People Are Most Likely to Succeed

Jeffrey Kluger

Jeffrey Kluger (b. 1954) is a senior editor of science and technology reporting at Time magazine. He has written several books, including Splendid Solution (2006) and Simplexity: Why Simple Things Become Complex (2008), and coauthored Lost Moon: The Perilous Journey of Apollo 13, the book that was the basis for the movie Apollo 13, released in 1995. In his essay “Ambition: Why Some People Are Most Likely to Succeed,” written for Time in 2005, Kluger explores possible reasons why some individuals are able to find great success in life while others struggle to get ahead.

You don’t get as successful as Gregg and Drew Shipp by accident. Shake hands with the 36-

That did it. By the time they got out of school, both Shipps had entirely transformed themselves, changing from boys who might have grown up to live off the family’s wealth to men consumed with going out and creating their own. “At this point,” says Gregg, “I consider myself to be almost maniacally ambitious.”

It shows. In 1998 the brothers went into the gym trade. They spotted a modest health club doing a modest business, bought out the owner and transformed the place into a luxury facility where private trainers could reserve space for top-

Why is that? Why are some people born with a fire in the belly, while others — like the Shipps — need something to get their pilot light lit? And why do others never get the flame of ambition going? Is there a family anywhere that doesn’t have its overachievers and underachievers — its Jimmy Carters and Billy Carters, its Jeb Bushes and Neil Bushes — and find itself wondering how they all could have come splashing out of exactly the same gene pool?

5 Of all the impulses in humanity’s behavioral portfolio, ambition — that need to grab an ever bigger piece of the resource pie before someone else gets it — ought to be one of the most democratically distributed. Nature is a zero-

And yet it’s not. For every person consumed with the need to achieve, there’s someone content to accept whatever life brings. For everyone who chooses the 80-

Not only do we struggle to understand why some people seem to have more ambition than others, but we can’t even agree on just what ambition is. “Ambition is an evolutionary product,” says anthropologist Edward Lowe at Soka University of America, in Aliso Viejo, Calif. “No matter how social status is defined, there are certain people in every community who aggressively pursue it and others who aren’t so aggressive.”

Dean Simonton, a psychologist at the University of California, Davis, who studies genius, creativity and eccentricity, believes it’s more complicated than that. “Ambition is energy and determination,” he says. “But it calls for goals too. People with goals but no energy are the ones who wind up sitting on the couch saying ‘One day I’m going to build a better mousetrap.’ People with energy but no clear goals just dissipate themselves in one desultory project after the next.”

Assuming you’ve got drive, dreams and skill, is all ambition equal? Is the overworked lawyer on the partner track any more ambitious than the overworked parent on the mommy track? Is the successful musician to whom melody comes naturally more driven than the unsuccessful one who sweats out every note? We may listen to Mozart, but should we applaud Salieri?1

10 Most troubling of all, what about when enough ambition becomes way too much? Grand dreams unmoored from morals are the stuff of tyrants — or at least of Enron. The 16-

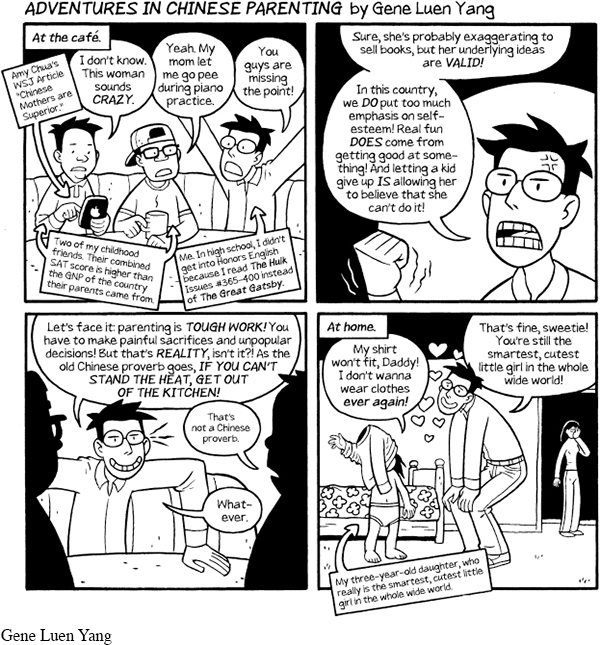

The Wall Street Journal asked Gene Luen Yang, the author of the graphic novel American Born Chinese, to offer his cartoon response to Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, a book written by Amy Chua.

Anthropologists, psychologists and others have begun looking more closely at these issues, seeking the roots of ambition in family, culture, gender, genes and more. They have by no means thrown the curtain all the way back, but they have begun to part it. “It’s fundamentally human to be prestige conscious,” says Soka’s Lowe. “It’s not enough just to be fed and housed. People want more.”

If humans are an ambitious species, it’s clear we’re not the only one. Many animals are known to signal their ambitious tendencies almost from birth. Even before wolf pups are weaned, they begin sorting themselves out into alphas and all the others. The alphas are quicker, more curious, greedier for space, milk, Mom — and they stay that way for life. Alpha wolves wander widely, breed annually and may live to a geriatric 10 or 11 years old. Lower-

Humans often report the same kind of temperamental determinism. Families are full of stories of the inexhaustible infant who grew up to be an entrepreneur, the phlegmatic child who never really showed much go. But if it’s genes that run the show, what accounts for the Shipps, who didn’t bestir themselves until the cusp of adulthood? And what, more tellingly, explains identical twins — precise genetic templates of each other who ought to be temperamentally identical but often exhibit profound differences in the octane of their ambition?

Ongoing studies of identical twins have measured achievement motivation — lab language for ambition — in identical siblings separated at birth, and found that each twin’s profile overlaps 30% to 50% of the other’s. In genetic terms, that’s an awful lot — “a benchmark for heritability,” says geneticist Dean Hamer of the National Cancer Institute. But that still leaves a great deal that can be determined by experiences in infancy, subsequent upbringing and countless other imponderables.

15 Some of those variables may be found by studying the function of the brain. At Washington University, researchers have been conducting brain imaging to investigate a trait they call persistence — the ability to stay focused on a task until it’s completed just so — which they consider one of the critical engines driving ambition.

The researchers recruited a sample group of students and gave each a questionnaire designed to measure persistence level. Then they presented the students with a task — identifying sets of pictures as either pleasant or unpleasant and taken either indoors or outdoors — while conducting magnetic resonance imaging of their brains. The nature of the task was unimportant, but how strongly the subjects felt about performing it well — and where in the brain that feeling was processed — could say a lot. In general, the researchers found that students who scored highest in persistence had the greatest activity in the limbic region, the area of the brain related to emotions and habits. “The correlation was .8 [or 80%],” says professor of psychiatry Robert Cloninger, one of the investigators. “That’s as good as you can get.”

It’s impossible to say whether innate differences in the brain were driving the ambitious behavior or whether learned behavior was causing the limbic to light up. But a number of researchers believe it’s possible for the non-

Is such an epiphany possible for all of us, or are some people immune to this kind of lightning? Are there individuals or whole groups for whom the amplitude of ambition is simply lower than it is for others? It’s a question — sometimes a charge — that hangs at the edges of all discussions about gender and work, about whether women really have the meat-

Economists Lise Vesterlund of the University of Pittsburgh and Muriel Niederle of Stanford University conducted a study in which they assembled 40 men and 40 women, gave them five minutes to add up as many two-

20 “Men and women just differ in their appetite for competition,” says Vesterlund. “There seems to be a dislike for it among women and a preference among men.”

To old-

As with so much viewed through the lens of anthropology, the roots of these differences lie in animal and human mating strategies. Males are built to go for quick, competitive reproductive hits and move on. Women are built for the it-

Import such tendencies into the 21st century workplace, and you get women who are plenty able to compete ferociously but are inclined to do it in teams and to split the difference if they don’t get everything they want. And mothers who appear to be unwilling to strive and quit the workplace al

“Being out in the world became a lot less important to me,” she says. “I used to worry about getting Presidents elected, and I’m still an incredibly ambitious person. But what I want to succeed at now is managing my family, raising my boys, helping my husband and the community. In 10 years, when the boys are launched, who knows what I’ll be doing? But for now, I have my world.”

25 But even if something as primal as the reproductive impulse wires you one way, it’s possible for other things to rewire you completely. Two of the biggest influences on your level of ambition are the family that produced you and the culture that produced your family.

There are no hard rules for the kinds of families that turn out the highest achievers. Most psychologists agree that parents who set tough but realistic challenges, applaud successes and go easy on failures produce kids with the greatest self-

What’s harder for parents to control but has perhaps as great an effect is the level of privilege into which their kids are born. Just how wealth or poverty influences drive is difficult to predict. Grow up in a rich family, and you can inherit either the tools to achieve (think both Presidents Bush) or the indolence of the aristocrat. Grow up poor, and you can come away with either the motivation to strive (think Bill Clinton) or the inertia of the hopeless. On the whole, studies suggest it’s the upper middle class that produces the greatest proportion of ambitious people — mostly because it also produces the greatest proportion of anxious people.

When measuring ambition, anthropologists divide families into four categories: poor, struggling but getting by, upper middle class, and rich. For members of the first two groups, who are fighting just to keep the electricity on and the phone bill paid, ambition is often a luxury. For the rich, it’s often unnecessary. It’s members of the upper middle class, reasonably safe economically but not so safe that a bad break couldn’t spell catastrophe, who are most driven to improve their lot. “It’s called status anxiety,” says anthropologist Lowe, “and whether you’re born to be concerned about it or not, you do develop it.”

But some societies make you more anxious than others. The U.S. has always been a me-

30 The study of high-

Demerath got very different results when he conducted research in a very different place — Papua, New Guinea.

In the mid-

That makes tactical sense. In a country based on farming and fishing, you need to know that if you get sick and can’t work your field or cast your net, someone else will do it for you. Putting on airs in the classroom is not the way to ensure that will happen.

Of course, once a collectivist not always a collectivist. Marcelo Suárez-

35 As a group, the immigrant children in his study are outperforming their U.S.-born peers. What’s more, the adults are dramatically out-

So this is a good thing, right? Striving people come here to succeed — and do. While there are plenty of benefits that undeniably come with learning the ways of ambition, there are plenty of perils too — many a lot uglier than high school students cheating on the trig final.

Human history has always been writ in the blood of broken alliances, palace purges and strong people or nations beating up on weak ones — all in the service of someone’s hunger for power or resources. “There’s a point at which you find an interesting kind of nerve circuitry between optimism and hubris,” says Warren Bennis, a professor of business administration at the University of Southern California and the author of three books on leadership. “It becomes an arrogance or conceit, an inability to live without power.”

While most ambitious people keep their secret Caesar tucked safely away, it can emerge surprisingly, even suddenly. Says Frans de Waal, a primatologist at the Yerkes Primate Center in Atlanta and the author of a new book, Our Inner Ape: “You can have a male chimp that is the most laid-

But a yearning for supremacy can create its own set of problems. Heart attacks, ulcers and other stress-

40 For these reasons, people and animals who have an appetite for becoming an alpha often settle contentedly into life as a beta. “The desire to be in a high position is universal,” says de Waal. “But that trait has co-

Humans not only make peace with their beta roles but they also make money from them. Among corporations, an increasingly well-

Ultimately, it’s that very flexibility — that multiplicity of possible rewards — that makes dreaming big dreams and pursuing big goals worth all the bother. Ambition is an expensive impulse, one that requires an enormous investment of emotional capital. Like any investment, it can pay off in countless different kinds of coin. The trick, as any good speculator will tell you, is recognizing the riches when they come your way.

Understanding and Interpreting

Kluger cites a study led by economists from the University of Pittsburgh and Stanford University that looked at the difference in appetite for competition between males and females (par. 19). What connection does Kluger make between competition and ambition, and how does that connection support the goals of his essay?

Kluger addresses the issue of the level of financial privilege into which an individual is born. What are the advantages and disadvantages of being born into privilege? In what ways does this discussion about privilege support Kluger’s goals in his argument?

While there are many benefits to being ambitious, there are also a number of drawbacks. According to Kluger, what are some of the possible problems associated with ambition? Do these problems outweigh the benefits in some cases? Explain.

Taking the entire essay into account, discuss how Kluger structures his argument. What is the order in which he makes his points, how does he develop them, and what connections does he draw between his different points?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Using evidence from the text, explain how Kluger develops his definition of ambition over the course of the essay. Pay specific attention to the types of evidence he uses to support his claims.

Throughout the essay, Kluger uses examples from the animal kingdom to make points about the roots of human ambition. To what degree are these examples helpful in reinforcing his argument, and in what ways does introducing these examples lead to possible objections?

Kluger begins his essay with an anecdote about two brothers who entirely transform themselves after finishing college. In what ways is this example an effective way to begin an essay about the nature of ambition?

In paragraph 5, Kluger asserts that ambition as a quality seems like it should be “democratically distributed,” yet it isn’t. What specific rebuttals does he give to refute the notion of equal distribution of ambition? Do you agree with his rebuttals, or do you think there is something he is not considering?

Kluger not only discusses the benefits of ambition but also raises the possibility that ambition can go too far. The examples he uses include the immoral choices that executives at Enron made in their pursuit of success (par. 10), as well as students who are “triple-

booked with advanced- placement courses, sports and after- school jobs” and reportedly feeling under stress some or all of the time (par. 10). What effect do these negative examples of ambition have on his overall discussion of ambition? Kluger cites a number of different findings from various research studies over the course of his essay. What do the types of research studies he cites have in common? Try to identify a pattern in the way he uses research to support his main assertions.

In his essay, Kluger sometimes makes an assertion about ambition based on selected evidence and then contradicts that evidence in the following paragraph. In what ways is this an effective approach to making his argument and in what ways might it undermine his purpose?

Kluger introduces the idea of “status anxiety” (par. 28) when discussing the influence of family and culture on ambition. How does he use this concept to further his overall argument?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Do you consider yourself to be an ambitious person, as outlined in Kluger’s essay? Do you think that ambition is of primary importance, or is it more important just to be happy—

whether that means being ambitious or not? Kluger begins his essay with the story of two ambitious brothers who have found considerable success in the fitness industry. These two men, according to Kluger, only became ambitious after completing their college education, when they needed to figure out how to become successful without simply inheriting the family business. In other words, they were motivated by external forces. In your personal experience, what motivates you to take action? Are you an individual who is intrinsically motivated and naturally works hard? Or do you need some kind of external motivation in order to take specific action? Cite a specific example from Kluger’s article that may help explain why you believe you are extrinsically or intrinsically motivated.

Kluger identifies self-

confidence and privilege as two driving factors that determine how ambitious a person will be. According to psychologists, self- confidence can be fostered by parents who “set tough but realistic challenges, applaud successes and go easy on failures” (par. 26). Discuss this balance that psychologists describe. Do you think these three factors are important to developing self- confident children, and, if so, how important do you think the relationship is between self- confidence and ambition? If you don’t agree with the psychologists’ theories about the development of self- confidence, what do you think they are failing to recognize about human nature? Kluger takes into account the experiences of students in a high-

performing school who report feeling stressed or overwhelmed by the amount of work they do both in and outside of school. Create a survey for your classmates that either confirms or refutes this example in your school. In creating your survey, consider what questions you can ask that will best reveal how your peers feel about their ability to balance success in school with their ability to also enjoy their lives. Once you have created your questions and given the survey to a number of your peers, evaluate the results to see if they support the original study’s conclusions or if the situation is significantly different in your school. Kluger cites a study that concludes that men and women have different appetites for competition. In your experience both in and outside of school, do you see this difference between males and females? Use your personal experience to argue whether or not this difference exists, and cite specific examples that lead you to your conclusions.