from An Ideal for Which I Am Prepared to Die

Nelson Mandela

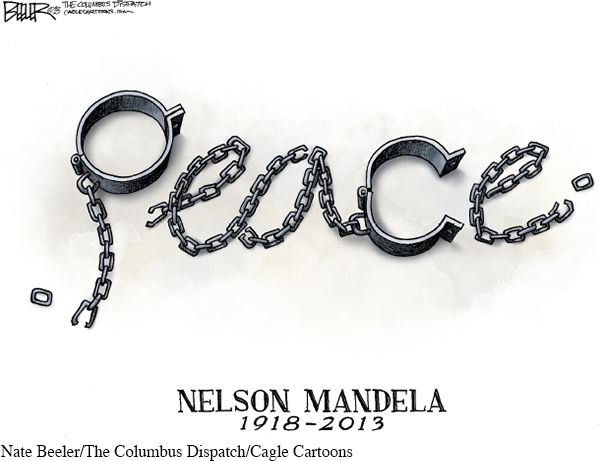

Nobel Peace Prize recipient Nelson Mandela (1918–

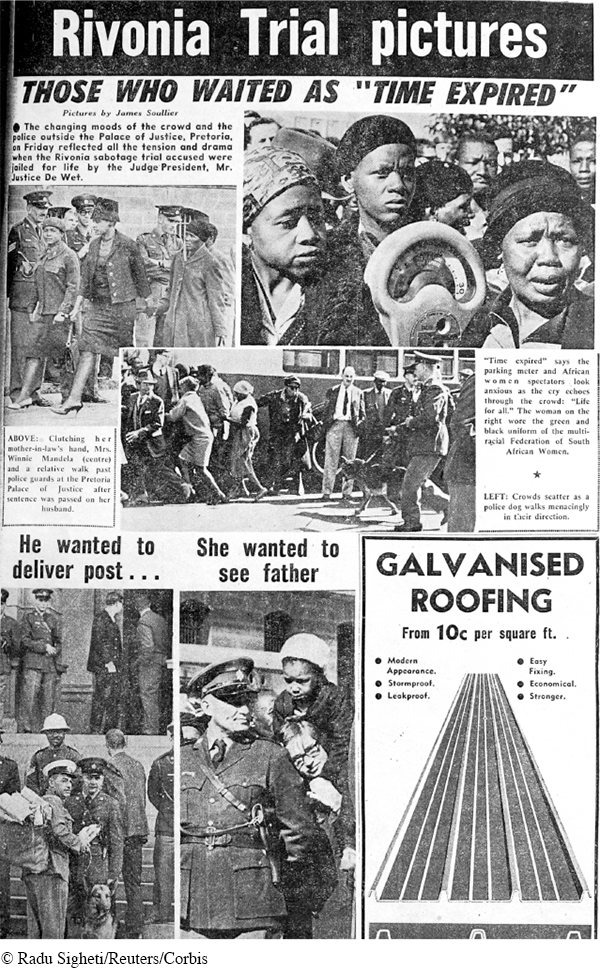

KEY CONTEXT Long before he became the president of South Africa and a Nobel Prize winner, Nelson Mandela fought against a system known as apartheid, the racial segregation of people within South Africa. As a result, Mandela faced constant persecution from the ruling political party in South Africa at the time, the National Party. Mandela was arrested four times, in 1952, 1956, 1962, and then again in 1963, when he was tried along with ten other defendants in what is called the Rivonia Trial.

Mandela stood accused of four broad charges: “(a) recruiting persons for training in the preparation and use of explosives and in guerrilla warfare for the purpose of violent revolution and committing acts of sabotage; (b) conspiring to commit these acts and to aid foreign military units when they [hypothetically] invaded the Republic; (c) acting in these ways to further the objectives of communism; and (d) soliciting and receiving money for these purposes from sympathizers outside South Africa.” Due to a justice system that was beholden to the ruling National Party, Mandela was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

When he was finally released after spending twenty-

What follows is a portion of Mandela’s speech delivered in the courtroom at the opening of the defense case in the Rivonia Trial. Although he was eventually convicted of the charges, the speech became a rallying point for opposition leaders and is considered to be one of the most compelling and important speeches made by Mandela in his illustrious career.

I am the first accused. I hold a bachelor’s degree in arts and practised as an attorney in Johannesburg for a number of years in partnership with Oliver Tambo. I am a convicted prisoner serving five years for leaving the country without a permit and for inciting people to go on strike at the end of May 1961.

At the outset, I want to say that the suggestion made by the state in its opening that the struggle in South Africa is under the influence of foreigners or communists is wholly incorrect. I have done whatever I did, both as an individual and as a leader of my people, because of my experience in South Africa and my own proudly felt African background, and not because of what any outsider might have said.

In my youth in the Transkei1 I listened to the elders of my tribe telling stories of the old days. Amongst the tales they related to me were those of wars fought by our ancestors in defence of the fatherland. The names of Dingane and Bambata, Hintsa and Makana, Squngthi and Dalasile, Moshoeshoe and Sekhukhuni,2 were praised as the glory of the entire African nation. I hoped then that life might offer me the opportunity to serve my people and make my own humble contribution to their freedom struggle. This is what has motivated me in all that I have done in relation to the charges made against me in this case.

Having said this, I must deal immediately and at some length with the question of violence. Some of the things so far told to the court are true and some are untrue. I do not, however, deny that I planned sabotage. I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation, and oppression of my people by the whites.

5 I admit immediately that I was one of the persons who helped to form Umkhonto we Sizwe,3 and that I played a prominent role in its affairs until I was arrested in August 1962. [. . .]

I, and the others who started the organisation, did so for two reasons. Firstly, we believed that as a result of Government policy, violence by the African people had become inevitable, and that unless responsible leadership was given to canalise and control the feelings of our people, there would be outbreaks of terrorism which would produce an intensity of bitterness and hostility between the various races of this country which is not produced even by war. Secondly, we felt that without violence there would be no way open to the African people to succeed in their struggle against the principle of white supremacy. All lawful modes of expressing opposition to this principle had been closed by legislation, and we were placed in a position in which we had either to accept a permanent state of inferiority, or to defy the government. We chose to defy the law. We first broke the law in a way which avoided any recourse to violence; when this form was legislated against, and then the government resorted to a show of force to crush opposition to its policies, only then did we decide to answer violence with violence.

But the violence which we chose to adopt was not terrorism. We who formed Umkhonto were all members of the African National Congress, and had behind us the ANC tradition of non-

Consider this political cartoon in response to Mandela’s passing in 2013.

In the words of my leader, Chief Lutuli, who became President of the ANC in 1952, and who was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize:

Who will deny that thirty years of my life have been spent knocking in vain, patiently, moderately, and modestly at a closed and barred door? What have been the fruits of moderation? The past thirty years have seen the greatest number of laws restricting our rights and progress, until today we have reached a stage where we have almost no rights at all.

[. . .] What were we, the leaders of our people, to do? Were we to give in to the show of force and the implied threat against future action, or were we to fight it and, if so, how?

10 We had no doubt that we had to continue the fight. Anything else would have been abject surrender. Our problem was not whether to fight, but was how to continue the fight. We of the ANC had always stood for a non-

At the beginning of June 1961, after a long and anxious assessment of the South African situation, I, and some colleagues, came to the conclusion that as violence in this country was inevitable, it would be unrealistic and wrong for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-

This conclusion was not easily arrived at. It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle, and to form Umkhonto we Sizwe. We did so not because we desired such a course, but solely because the government had left us with no other choice. In the Manifesto of Umkhonto published on 16 December 1961, which is exhibit AD, we said:

The time comes in the life of any nation when there remain only two choices — submit or fight. That time has now come to South Africa. We shall not submit and we have no choice but to hit back by all means in our power in defence of our people, our future, and our freedom.

[. . .] When we took this decision, and subsequently formulated our plans, the ANC heritage of non-

The avoidance of civil war had dominated our thinking for many years, but when we decided to adopt violence as part of our policy, we realised that we might one day have to face the prospect of such a war. This had to be taken into account in formulating our plans. We required a plan which was flexible and which permitted us to act in accordance with the needs of the times; above all, the plan had to be one which recognised civil war as the last resort, and left the decision on this question to the future. We did not want to be committed to civil war, but we wanted to be ready if it became inevitable.

15 Four forms of violence were possible. There is sabotage, there is guerrilla warfare, there is terrorism, and there is open revolution. We chose to adopt the first method and to exhaust it before taking any other decision.

In the light of our political background the choice was a logical one. Sabotage did not involve loss of life, and it offered the best hope for future race relations. Bitterness would be kept to a minimum and, if the policy bore fruit, democratic government could become a reality. This is what we felt at the time, and this is what we said in our manifesto (exhibit AD):

We of Umkhonto we Sizwe have always sought to achieve liberation without bloodshed and civil clash. We hope, even at this late hour, that our first actions will awaken everyone to a realisation of the disastrous situation to which the nationalist policy is leading. We hope that we will bring the government and its supporters to their senses before it is too late, so that both the government and its policies can be changed before matters reach the desperate state of civil war.

The initial plan was based on a careful analysis of the political and economic situation of our country. We believed that South Africa depended to a large extent on foreign capital and foreign trade. We felt that planned destruction of power plants, and interference with rail and telephone communications, would tend to scare away capital from the country, make it more difficult for goods from the industrial areas to reach the seaports on schedule, and would in the long run be a heavy drain on the economic life of the country, thus compelling the voters of the country to reconsider their position.

Attacks on the economic life-

In addition, if mass action were successfully organised, and mass reprisals taken, we felt that sympathy for our cause would be roused in other countries, and that greater pressure would be brought to bear on the South African government.

20 This then was the plan. Umkhonto was to perform sabotage, and strict instructions were given to its members right from the start, that on no account were they to injure or kill people in planning or carrying out operations. [. . .]

Umkhonto had its first operation on 16 December 1961, when Government buildings in Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth and Durban were attacked. The selection of targets is proof of the policy to which I have referred. Had we intended to attack life we would have selected targets where people congregated and not empty buildings and power stations. [. . .]

The Manifesto of Umkhonto was issued on the day that operations commenced. The response to our actions and manifesto among the white population was characteristically violent. The government threatened to take strong action, and called upon its supporters to stand firm and to ignore the demands of the Africans. The whites failed to respond by suggesting change; they responded to our call by suggesting the laager.4

In contrast, the response of the Africans was one of encouragement. Suddenly there was hope again. Things were happening. People in the townships became eager for political news. A great deal of enthusiasm was generated by the initial successes, and people began to speculate on how soon freedom would be obtained. But we in Umkhonto weighed up the white response with anxiety. The lines were being drawn. The whites and blacks were moving into separate camps, and the prospects of avoiding a civil war were made less. The white newspapers carried reports that sabotage would be punished by death. If this was so, how could we continue to keep Africans away from terrorism? [. . .]

How do these images from the media coverage of the trial reflect the racial division that Mandela was fighting against? Do you think the newspaper was expressing support for Mandela’s cause in its selection of these images? Explain.

Our fight is against real, and not imaginary, hardships or, to use the language of the state prosecutor, “so-

25 South Africa is the richest country in Africa, and could be one of the richest countries in the world. But it is a land of extremes and remarkable contrasts. The whites enjoy what may well be the highest standard of living in the world, whilst Africans live in poverty and misery. Forty per cent of the Africans live in hopelessly overcrowded and, in some cases, drought-

Poverty goes hand in hand with malnutrition and disease. The incidence of malnutrition and deficiency diseases is very high amongst Africans. Tuberculosis, pellagra, kwashiorkor, gastro-

The complaint of Africans, however, is not only that they are poor and the whites are rich, but that the laws which are made by the whites are designed to preserve this situation. There are two ways to break out of poverty. The first is by formal education, and the second is by the worker acquiring a greater skill at his work and thus higher wages. As far as Africans are concerned, both these avenues of advancement are deliberately curtailed by legislation.

The present government has always sought to hamper Africans in their search for education. One of their early acts, after coming into power, was to stop subsidies for African school feeding. Many African children who attended schools depended on this supplement to their diet. This was a cruel act.

There is compulsory education for all white children at virtually no cost to their parents, be they rich or poor. Similar facilities are not provided for the African children, though there are some who receive such assistance. African children, however, generally have to pay more for their schooling than whites. According to figures quoted by the South African Institute of Race Relations in its 1963 journal, approximately 40 per cent of African children in the age group between seven to fourteen do not attend school. [. . .]

30 The quality of education is also different. According to the Bantu Educational Journal, only 5,660 African children in the whole of South Africa passed their junior certificate in 1962, and in that year only 362 passed matric.5 This is presumably consistent with the policy of Bantu education about which the present Prime Minister said, during the debate on the Bantu Education Bill in 1953:

When I have control of native education I will reform it so that natives will be taught from childhood to realise that equality with Europeans is not for them . . . People who believe in equality are not desirable teachers for natives. When my Department controls native education it will know for what class of higher education a native is fitted, and whether he will have a chance in life to use his knowledge.

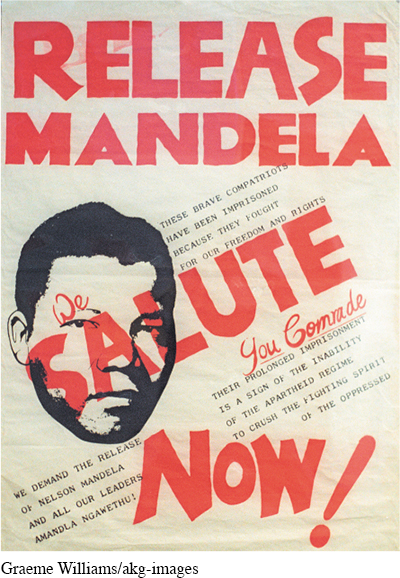

Examine this 1989 poster in support of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. The small print reads: “These brave compatriots have been imprisoned because they fought for our freedom and rights[.] We demand the release of Nelson Mandela and all our leaders Amandla Ngawethu! Their prolonged imprisonment is a sign of the inability of the apartheid regime to crush the fighting spirit of the oppressed[.]”

The other main obstacle to the economic advancement of the African is the industrial colour-

The government often answers its critics by saying that Africans in South Africa are economically better off than the inhabitants of the other countries in Africa. I do not know whether this statement is true and doubt whether any comparison can be made without having regard to the cost-

The lack of human dignity experienced by Africans is the direct result of the policy of white supremacy. White supremacy implies black inferiority. Legislation designed to preserve white supremacy entrenches this notion. Menial tasks in South Africa are invariably performed by Africans. When anything has to be carried or cleaned the white man will look around for an African to do it for him, whether the African is employed by him or not. Because of this sort of attitude, whites tend to regard Africans as a separate breed. They do not look upon them as people with families of their own; they do not realise that they have emotions — that they fall in love like white people do; that they want to be with their wives and children like white people want to be with theirs; that they want to earn enough money to support their families properly, to feed and clothe them and send them to school. And what “house-

Poverty and the breakdown of family life have secondary effects. Children wander about the streets of the townships because they have no schools to go to, or no money to enable them to go to school, or no parents at home to see that they go to school, because both parents (if there be two) have to work to keep the family alive. This leads to a breakdown in moral standards, to an alarming rise in illegitimacy, and to growing violence which erupts not only politically, but everywhere. Life in the townships is dangerous. There is not a day that goes by without somebody being stabbed or assaulted. And violence is carried out of the townships in to the white living areas. People are afraid to walk alone in the streets after dark. Housebreakings and robberies are increasing, despite the fact that the death sentence can now be imposed for such offences. Death sentences cannot cure the festering sore. [. . .]

35 Africans want to be paid a living wage. Africans want to perform work which they are capable of doing, and not work which the government declares them to be capable of. Africans want to be allowed to live where they obtain work, and not be endorsed out of an area because they were not born there. Africans want to be allowed to own land in places where they work, and not to be obliged to live in rented houses which they can never call their own. Africans want to be part of the general population, and not confined to living in their own ghettoes. African men want to have their wives and children to live with them where they work, and not be forced into an unnatural existence in men’s hostels. African women want to be with their menfolk and not be left permanently widowed in the Reserves. Africans want to be allowed out after eleven o’clock at night and not to be confined to their rooms like little children. Africans want to be allowed to travel in their own country and to seek work where they want to and not where the labour bureau tells them to. Africans want a just share in the whole of South Africa; they want security and a stake in society.

Above all, we want equal political rights, because without them our disabilities will be permanent. I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country, because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy.

But this fear cannot be allowed to stand in the way of the only solution which will guarantee racial harmony and freedom for all. It is not true that the enfranchisement of all will result in racial domination. Political division, based on colour, is entirely artificial and, when it disappears, so will the domination of one colour group by another. [. . .]

This then is what the ANC is fighting. Their struggle is a truly national one. It is a struggle of the African people, inspired by their own suffering and their own experience. It is a struggle for the right to live.

During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

Understanding and Interpreting

Look back at the Key Context section before this piece, and think about the charges that Mandela stands trial for. What does the nature of those charges tell you about the political context of this speech?

What distinction does Mandela make between “violence” and “terrorism” (par. 7), and what purpose does this distinction serve?

Explain the concept of a “non-

racial democracy” (par. 10) and why this is of central concern to Mandela and the ANC. How does Mandela justify abandoning nonviolent protest and how does he make the case for sabotage as his preferred alternative? How does this reasoning support his overall argument in this speech?

Mandela says that the “complaint of Africans, however, is not only that they are poor and the whites are rich, but that the laws which are made by the whites are designed to preserve this situation” (par. 27). Explain the distinction he is making and why it is important in terms of his overall justification for violent resistance.

Mandela addresses the state of education in South Africa at the time. What are the main points he raises, and how do the issues he discusses perpetuate the inequalities of apartheid?

Mandela references the “industrial colour-

bar” (par. 31) when discussing economic advancement. To what is he referring and what evidence does he cite in support of his use of this term? What large social problems does Mandela link to the “policy of white supremacy” (par. 33) and what logic does he use to make this connection?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

How does opening with a counterargument help Mandela establish his overall purpose?

Mandela provides two reasons for establishing the resistance group Umkhonto. How effectively do these reasons justify the organization’s actions?

What purpose does quoting Chief Lutuli serve in Mandela’s argument (par. 8)? In your response, consider both the quote itself as well as the speaker.

In what ways does Mandela use the prospect of civil war in South Africa to explain the choice to adopt a more violent approach?

Mandela states that the “whites failed to respond [to the Manifesto of Umkhonto] by suggesting change; they responded to our call by suggesting the laager” (par. 22). Laager is an Afrikaans (South African Dutch) word, so it is closely associated with the white National Party that was largely responsible for the imprisonment of political activists such as Mandela. Its original meaning was a camp formed by a circle of wagons. It later came to mean an entrenched position or viewpoint that is defended against opponents. How might the choice of the term laager reinforce Mandela’s justification for the use of violent opposition to the government?

Notice the repeated use of the phrase “so-

called” in paragraph 24. Explain how Mandela uses that phrase as a rhetorical tool in that paragraph. Mandela discusses education and economic opportunities, which lead to his assertion that “[w]hite supremacy implies black inferiority” and that “[l]egislation designed to preserve white supremacy entrenches this notion” (par. 33). Discuss how the order of his evidence and the specific examples he uses build to this assertion.

Explain how Mandela’s statement that “[p]olitical division, based on colour, is entirely artificial and, when it disappears, so will the domination of one colour group by another” (par. 37) is linked to his argument as a whole.

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Mandela gave numerous speeches during his career as a political activist. Research other speeches he made, and then select one that you find inspiring. Then, create a PowerPoint presentation using words from the speech you select and images (from various sources) that capture the tone of the speech.

Mandela was imprisoned for standing up against a white supremacist government whose primary purpose was to ensure white privilege and institutionalize inferiority for nonwhite South Africans. As he indicates in his speech, he changed his stance from one of passive, nonviolent resistance to one that embraced the need to engage in violent opposition. Write an argument in which you address the following questions: Was Nelson Mandela justified in the use of violence to overthrow apartheid? What does it mean that he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in spite of his call for violent opposition?

Find Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” online and consider the similarities between this speech and Mandela’s. Specifically consider the ways in which both King and Mandela use the circumstances of their imprisonment to advance their individual causes.

Mandela put his life on the line, and ultimately sacrificed his freedom in pursuit of his cause. Consider a current political, social, or economic issue that you consider to be of great importance. Then, write a persuasive speech in which you explain the issue, why you believe it’s important, why you believe others should agree with your position, and what you would be willing to do in order to support your position. This can be an issue related to your school, your local community, the entire nation, or even the global community.

Mandela was called a rebel and ultimately imprisoned for his political views as he strove for justice. In spite of his long imprisonment, he inspired lasting change in his country and around the world. Research other leaders who have also been imprisoned for their activism and were nonetheless able to motivate powerful and lasting change, selecting one whom you find particularly compelling. Then prepare a presentation in which you share the ways in which the leader you selected influenced or changed the world.