from Common Sense

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (1737–

KEY CONTEXT Paine arrived in Philadelphia just as the conflict between the colonies and England was becoming especially intense, as many colonists were calling for independence from England. The initial revolt against England focused on the colonists’ anger over taxation from the king, but after the first battles of the Revolutionary War, Paine argued that the colonists should not merely resist taxation but rather fight for complete independence from England. He explained his ideas concerning the necessity of independence in a fifty-

Thoughts of the Present State of American Affairs

In the following pages I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense; and have no other preliminaries to settle with the reader, than that he will divest himself of prejudice and prepossession, and suffer his reason and his feelings to determine for themselves; that he will put on, or rather that he will not put off the true character of a man, and generously enlarge his views beyond the present day.

Volumes have been written on the subject of the struggle between England and America. Men of all ranks have embarked in the controversy, from different motives, and with various designs; but all have been ineffectual, and the period of debate is closed. Arms, as the last resource, decide the contest; the appeal1 was the choice of the king, and the continent hath accepted the challenge.

It hath been reported of the late Mr. Pelham2 (who tho’ an able minister was not without his faults) that on his being attacked in the house of commons, on the score, that his measures were only of a temporary kind, replied, “they will last my time.” Should a thought so fatal and unmanly possess the colonies in the present contest, the name of ancestors will be remembered by future generations with detestation.

The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ’Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent — of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed time of continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

5 By referring the matter from argument to arms, a new area for politics is struck; a new method of thinking hath arisen. All plans, proposals, &c. prior to the nineteenth of April, i.e., to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacs of the last year; which, though proper then, are superseded and useless now. Whatever was advanced by the advocates on either side of the question then, terminated in one and the same point, viz., a union with Great Britain; the only difference between the parties was the method of effecting it; the one proposing force, the other friendship; but it hath so far happened that the first hath failed, and the second hath withdrawn her influence.

As much hath been said of the advantages of reconciliation, which, like an agreeable dream, hath passed away and left us as we were, it is but right, that we should examine the contrary side of the argument, and inquire into some of the many material injuries which these colonies sustain, and always will sustain, by being connected with, and dependant on Great Britain. To examine that connection and dependance, on the principles of nature and common sense, to see what we have to trust to, if separated, and what we are to expect, if dependant.

I have heard it asserted by some, that as America hath flourished under her former connection with Great Britain, that the same connection is necessary towards her future happiness, and will always have the same effect. Nothing can be more fallacious than this kind of argument. We may as well assert, that because a child has thrived upon milk, that it is never to have meat; or that the first twenty years of our lives is to become a precedent for the next twenty. But even this is admitting more than is true, for I answer roundly, that America would have flourished as much, and probably much more, had no European power had anything to do with her. The commerce by which she hath enriched herself are the necessaries of life, and will always have a market while eating is the custom of Europe.

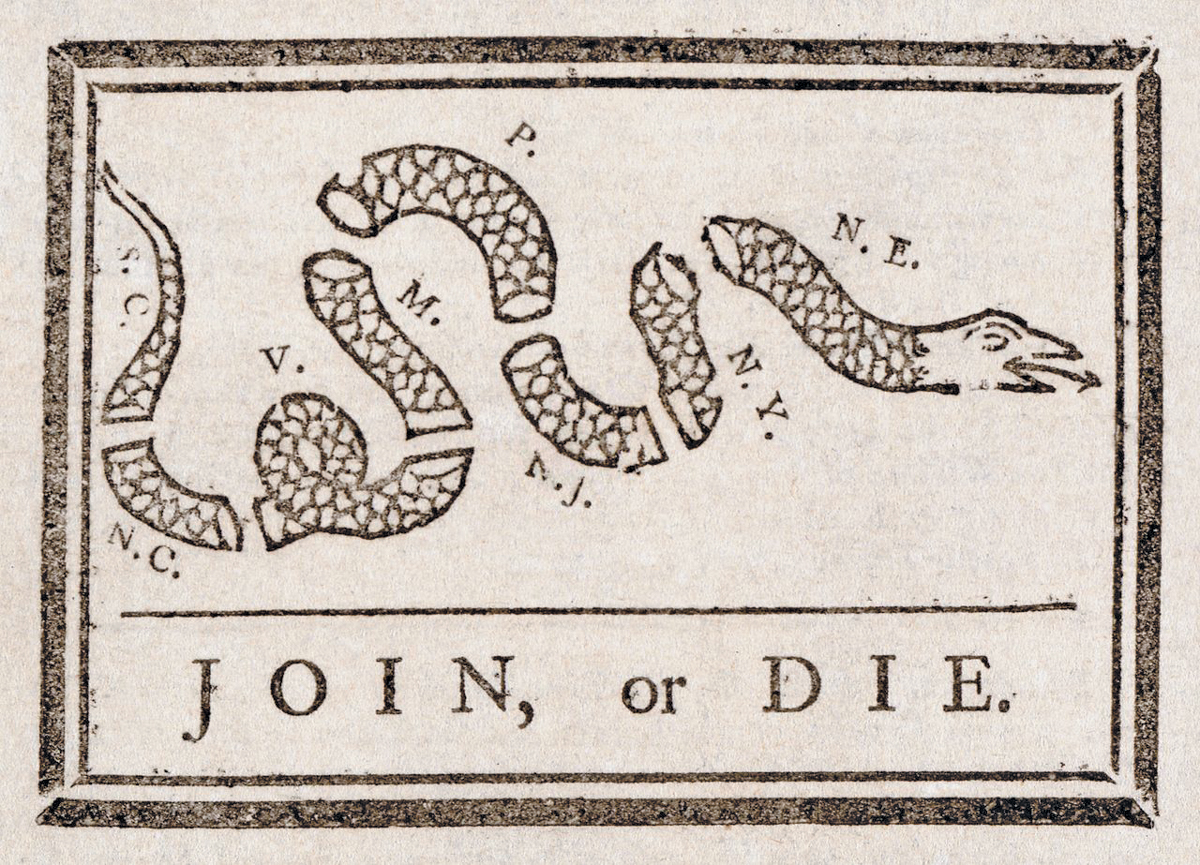

This is a political cartoon created by Ben Franklin and published in his Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754. The sections of the “snake” represent different colonies.

But she has protected us, say some. That she hath engrossed us is true, and defended the continent at our expense as well as her own is admitted, and she would have defended Turkey from the same motive, viz., the sake of trade and dominion.

Alas, we have been long led away by ancient prejudices and made large sacrifices to superstition. We have boasted the protection of Great Britain, without considering, that her motive was interest not attachment; that she did not protect us from our enemies on our account, but from her enemies on her own account, from those who had no quarrel with us on any other account, and who will always be our enemies on the same account. Let Britain wave her pretensions to the continent, or the continent throw off the dependance, and we should be at peace with France and Spain were they at war with Britain. The miseries of Hanover last war ought to warn us against connections.

10 It hath lately been asserted in parliament, that the colonies have no relation to each other but through the parent country, i.e., that Pennsylvania and the Jerseys, and so on for the rest, are sister colonies by the way of England; this is certainly a very roundabout way of proving relationship, but it is the nearest and only true way of proving enemyship, if I may so call it. France and Spain never were, nor perhaps ever will be our enemies as Americans, but as our being the subjects of Great Britain.

But Britain is the parent country, say some. Then the more shame upon her conduct. Even brutes do not devour their young; nor savages make war upon their families; wherefore the assertion, if true, turns to her reproach; but it happens not to be true, or only partly so, and the phrase parent or mother country hath been jesuitically adopted by the king and his parasites, with a low papistical design of gaining an unfair bias on the credulous weakness of our minds. Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every Part of Europe. Hither have they fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home pursues their descendants still.

Understanding and Interpreting

Paine states that he has no other “preliminaries,” or conditions, for the reader other than that the reader divest himself of “prejudice and prepossession” (par. 1) before reading the text. What is Paine asking of the reader, and why is it important at this point?

In paragraph 3, Paine refers to a statement made by “the late Mr. Pelham” that measures put in place would “last [his] time.” Why does Paine consider this statement “fatal and unmanly” with respect to the situation the colonies face?

Paine discusses several advantages that have been offered as reasons for reconciling with England. Identify each of the so-

called advantages that Paine mentions and then explain how he refutes each one. Explain what Paine means by “enemyship” (par. 10), and why, according to Paine, that term explains the relationship between the colonies and other countries that are in conflict with Great Britain.

Paine claims that “Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America” (par. 11). Explain the reasoning behind his assertion.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Consider the first sentence of the passage. How do the connotations of the adjectives “simple,” “plain,” and “common” help Paine establish the tone of his argument?

At the end of the second paragraph, Paine indicates that the “continent,” meaning the colonies, accepted the challenge of battle. What is the effect of beginning his argument with an acknowledgment that an armed conflict seems inevitable?

Explain how the simile regarding the “name engraved” on the “tender rind of a young oak” (par. 4) illustrates the significance of the cause that Paine is discussing.

In paragraph 5, Paine refers to the “commencement of hostilities” on the “nineteenth of April,” a reference to the battle of Lexington and Concord, which marked the beginning of armed conflict between the colonies and Great Britain. Explain how the simile the “almanacs of the last year” advances how Paine wishes the reader to understand the current situation.

Paine asserts that the protection of England was motivated by “interest not attachment” (par. 9). How do the connotations of these words serve to advance his argument while at the same time acknowledging the practical nature of the relationship between the colonies and England?

Paine advances a complex argument that encompasses several points. Explain how the structure of his argument, specifically the order in which he introduces his points, is effective in achieving his rhetorical purpose for his intended audience.

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Paine’s Common Sense is considered one of the primary founding documents in American history. Research the background of Paine and his influence on the American Revolution and Declaration of Independence. and prepare a presentation that argues what his impact was in shaping modern America.

Paine was a common target of British propaganda during the Revolutionary War. One coin used in British camps read “End of Pain” and showed Thomas Paine hanged from the gallows. Research other examples in which Paine was used by Britain as war propaganda and provide a written or oral presentation analyzing one example of how Paine was used to motivate British soldiers to fight against the Continental Army.