Step 6: Write Your Body Paragraphs

At some point in your education, you may have heard that an essay is supposed to have five paragraphs: an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Your argumentative essay might, in fact, have five paragraphs, but it also might have four or fourteen, or any other number in between or beyond, depending on the complexity of your argument, and the scope of the project you have been given. Nelson Mandela’s speech, “An Ideal for Which I Am Prepared to Die,” for instance, reportedly went on for over two hours, while Malala Yousafzai’s address at the U.N. took about twenty minutes. The point is that your argument should be as long as it needs to be to convince your audience of your claim. This is not to say that there are no guidelines at all for how you make your argument. In general, you should have an introduction and a conclusion, and include body paragraphs that provide a variety of evidence that is fully explained and connected to your claim. You should also address the significant counterarguments to your claim.

Structuring a Paragraph

Just like the “five-

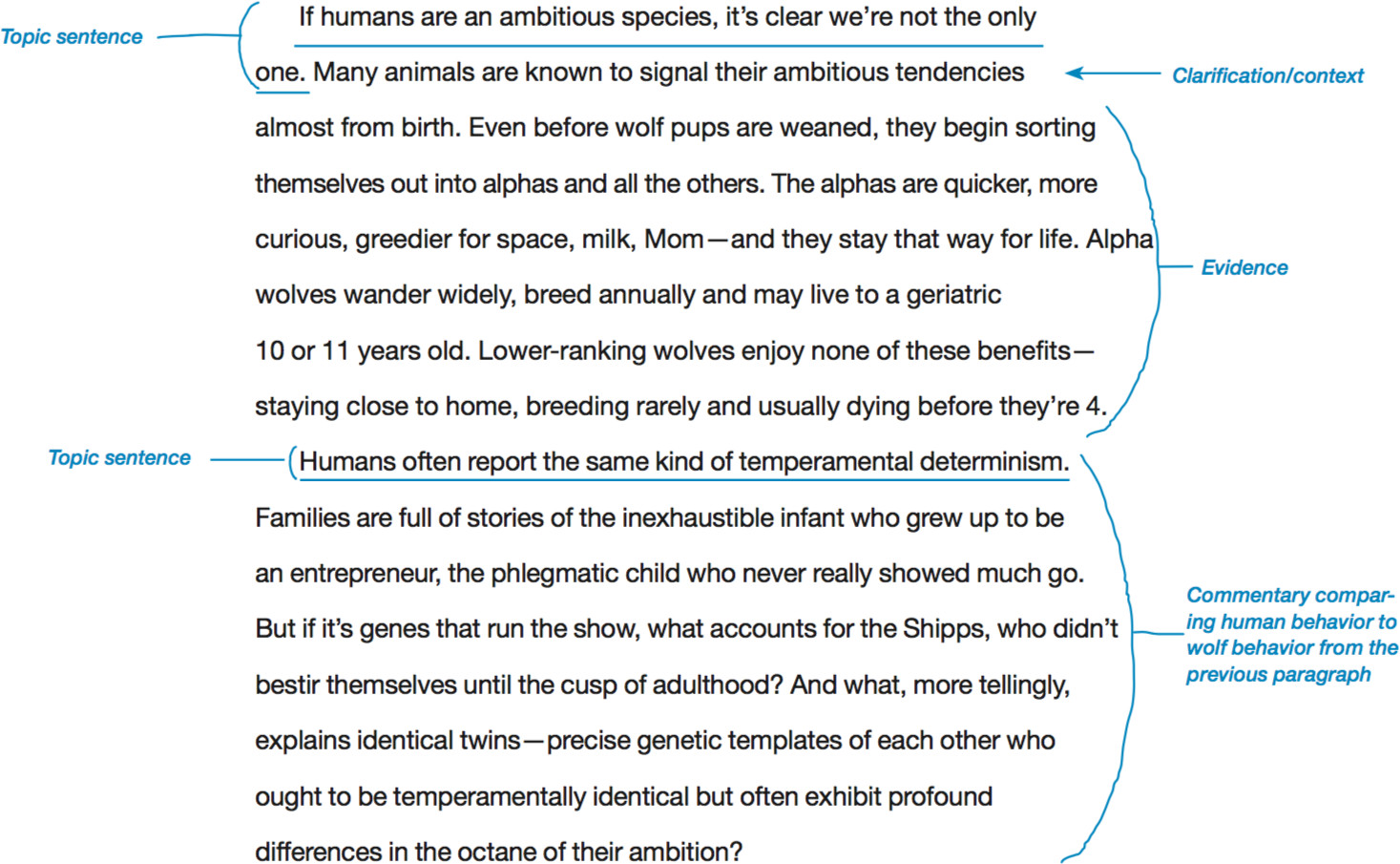

Again, this structure is not intended as a formula but is suggested as a guide for you to use as it fits for you and your argument. You can see how elements of this structure are in place in some of the paragraphs in this excerpt from “Ambition: Why Some People Are Most Likely to Succeed,” by Jeffrey Kluger:

Notice that Kluger spreads the evidence and commentary over two paragraphs. Again, the structure suggested above is not a rigid formula. The point here is that evidence should never stand on its own. It should be accompanied by commentary from you, the writer. In an argumentative essay, telling your audience what the evidence proves, and why it is relevant to your overall argument, is an important part of your job.

ACTIVITY

Write a draft of one or more body paragraphs of your argument, starting with the strongest reason that supports your claim. Be sure to use and explain the evidence. Use the format and the models above to guide you.

Addressing the Counterargument

An essential part of making your argument is to address the counterargument, the ideas that differ from the one you are using as your claim. These ideas are not necessarily against your entire position, but they might represent a different course of action, or might go beyond what you are willing to propose.

Some writers address the counterarguments immediately, at the beginning of their piece, acknowledging and quickly dismissing their opponents’ points. Other writers may wait until later in their argument, after they have made their strongest points. In Old Major’s speech in Animal Farm, he addresses the counterargument near the beginning, in order to remove the objection right away:

“No animal in England is free. The life of an animal is misery and slavery: that is the plain truth.

“But is this simply part of the order of nature? Is it because this land of ours is so poor that it cannot afford a decent life to those who dwell upon it? No, comrades, a thousand times no! The soil of England is fertile, its climate is good, it is capable of affording food in abundance to an enormously greater number of animals than now inhabit it.”

Given Old Major’s firebrand style, the refutation of the counterargument is a bit harsher than what we might expect in an academic paper, but note that Old Major supports his strident rejection with solid logical evidence.

The basic approach of addressing the counterarguments is to acknowledge and concede any valid points your opponents might make, and then refute the main thrust of their arguments. Unaddressed counterarguments linger in the minds of thoughtful readers who say, “Yeah, but what about _______?” Your job as a successful writer of arguments includes anticipating all reasonable objections to your claim and presenting evidence that your point of view is the most reasonable.

It may be tempting to use a phrase such as “Some people say . . . ,” but this only prompts readers to question: “Who?” Try, instead, to fully understand and describe the opposition’s position, and respectfully identify any noteworthy experts who hold that view.

Be careful to avoid the straw man logical fallacy in which you misrepresent the opposition or present an opponent’s view in an incomplete or exaggerated way just to make it easy to refute. Here is a straw man from President Obama’s second inaugural address: “We reject the belief that America must choose between caring for the generation that built this country and investing in the generation that will build its future.”

Whose belief is Obama referring to? Was anyone really suggesting that we shouldn’t care for the previous generations and invest in the future? Even people who opposed Obama’s fiscal policies likely never believed something so extreme. A straw man fallacy sets up the opposition’s weakest argument or misrepresents it for the sole purpose of refuting it. You build your own ethos by addressing opponents’ objections ethically and fully.

ACTIVITY

Write a draft of a body paragraph in which you address one of the strongest counterarguments to your claim. Describe it fully and ethically and be sure to refute it with evidence and reasoning. Also, consider where in your essay this paragraph will appear. Near the beginning or at the end? Or paired with a particular point you want to make? Why?