7

Ethics

How do we tell “right” from “wrong”?

Can there be a universal understanding of what is “right” or “wrong”?

To what extent do age, culture, and other factors affect our ethical decisions?

When making ethical decisions, whose needs should be most important? The individual’s, other people’s, the larger society’s?

What causes us to cheat? Is cheating always wrong? Who gets to define “cheating”?

Imagine that you are the operator of a train that has suddenly lost its brakes. Ahead of you on the tracks are five railroad workers who are unaware that you are moments away from slamming into them at a speed that will likely kill them all. But then, you notice that there is a split up ahead, which would allow you to switch to a different track, at the end of which is only one railroad worker. Your choice: keep on the first track and kill five, or switch tracks and kill only one. Do you kill the one to save the five? Why or why not?

This is a classic ethical dilemma that Michael Sandel, the author of the Central Text in this chapter, offers students in his justice course at Harvard University in order to illustrate the complexity of ethical choices. Philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson complicates the dilemma even further by asking you to imagine that you were no longer the operator, but instead a bystander on a bridge watching the train heading toward the five workers, and next to you on the bridge—

Obviously, these are situations that do not occur too frequently, but they can help us to clarify what we mean by “ethics.” As a branch of philosophy, ethics tries to articulate the reasons that some actions are considered “right” and others “wrong.” Just about everyone will say that killing is wrong, and yet, in scenarios such as the ones above, could killing sometimes be justified? Most people will say that stealing is wrong—

We know that different cultures, religions, and nations have different customs, laws, and practices, but do they also have different ethical codes? Philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote, “I cannot see how to refute the arguments for the subjectivity of ethical values, but I find myself incapable of believing that all that is wrong with wanton cruelty is that I don’t like it.” In other words, he expects that there should be some things that all people—

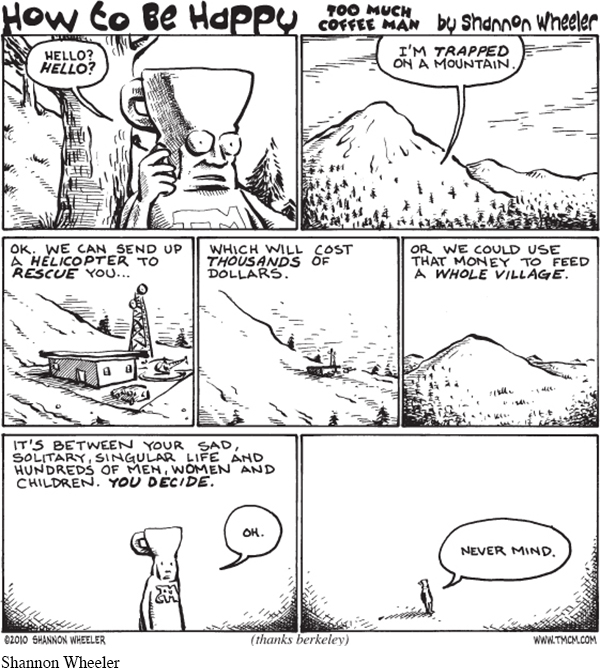

What essential ethical conflict does this cartoon rely on to make its point? Think of an example of this conflict from your own life.

OPENING ACTIVITY 1

Working with a partner or a small group, look through the following list and classify the actions as either “very bad,” “kind of bad,” or “not so bad.” Be prepared to share your reasoning for why you put each where you did:

robbing a bank

taking money from a parent without asking

cheating on a husband or wife

cheating on a girlfriend or boyfriend

copying answers during a test

copying homework

lying to your friends about why you didn’t meet up with them

lying to a friend about whether the terrible haircut he or she got looks good

illegally downloading a song from the Internet

stealing a CD from a music store

overcharging an insurance company if you are a doctor

overcharging a patient if you are a doctor

stealing a book from a bookstore

taking a library book without checking it out

going 15 miles per hour over the speed limit

texting while driving

driving while intoxicated

OPENING ACTIVITY 2

Read through the following scenarios and determine what you would do in each situation and why:

It is May of your senior year and your best friend has been accepted to Harvard on a full scholarship. Unfortunately, her mother has become very sick, and your friend has had to take care of her younger siblings, which has made it difficult for her to stay on top of her schoolwork and maintain the GPA required for her scholarship. She calls you one night in a panic because she has forgotten to do a major assignment due the following day and her teacher never accepts late work. You have completed the identical assignment for a different teacher. You go to a very big school and it is unlikely that either of the two teachers will ever see the other’s assignments, so if you let your friend copy your work, the chances of your being caught are not high. Nevertheless, your school has a zero tolerance policy for cheating, and if you are caught, both of you could be subject to severe punishments, including an automatic F in the class. Do you email your friend your assignment so that she can turn it in as her own work? Why or why not?

You are a parent of an eighteen-

year- old boy, and you, he, and your spouse are traveling to Singapore, a country with extremely strict drug laws. At the airport in Singapore, the security officials, using drug- sniffing dogs, begin looking closely at your son’s bag. You have suspected in the past that your son may have smoked marijuana, but you never knew for sure or confronted him about it. As the security officials move closer to the bag, you look at your son’s face, and you know for sure that he has brought marijuana with him. At the same time, you realize your spouse knows this as well and is preparing to take the blame for your son, which would likely lead to his or her serving many years in prison. When the security officials ask, “Whose bag is this?,” what do you do? Why? Page 414Imagine that you are working for a government intelligence agency. You captured a confirmed terrorist whom you suspect might have information about an imminent terrorist attack that you believe would result in the deaths of thousands of citizens. The terrorist is not offering the information willingly. Would you authorize torture on the terrorist if you thought it gave you a reasonable chance of preventing the attack? Why or why not?

The following scenario is a real-

life example from a famous court case in England called The Queen v. Dudley and Stephens. In 1884, four British men survived a shipwreck and floated for three weeks in a lifeboat in the Atlantic. When they ran out of food and water, the captain decided that they should draw straws to determine who would be killed and eaten in order to save the remaining three. The others refused. Eventually, the cabin boy became sick. When he was near death, the captain decided to kill him. The captain and the other two survivors ate his body, which kept them alive until they were rescued four days later. Upon returning to England, the captain was charged with murder. If you were on the jury, would you vote to convict the captain? Why or why not? The following scenario is a classic fictional ethical situation called “The Heinz Dilemma”: Imagine that you had a wife dying from a rare disease. A drug that might save her was available from a pharmacist in town, but he was charging $200,000, a sum that you could never pay and was ten times what the pharmacy paid for the drug wholesale. You borrowed all the money you could and went to the pharmacist with half the amount needed and asked him to sell the drug cheaper. When he refused, you became desperate and broke into the pharmacy to steal the drug. Should you have done that? More important, why or why not?