7.15

Cheating Upwards

Robert Kolker

Robert Kolker (b. 1969) is the author of Lost Girls (2013), about a series of unsolved Long Island, NY, murders and the lives of five victims. He is also a contributing editor and writer for New York magazine, from which this article has been taken.

KEY CONTEXT In this piece, Kolker examines an extensive cheating scandal that took place in June 2012 at Stuyvesant High School, an exclusive public high school in New York City that, unlike most public schools in the United States, has extraordinarily rigorous entrance requirements; typically, over twenty thousand students apply for only eight hundred spots. Through interviews with parents, students, and school administrators, Kolker tries to answer the question of why students, especially those at the most demanding schools, cheat.

On Wednesday, June 13, Nayeem Ahsan walked into a fourth-

The son of Bangladeshi immigrants, Nayeem was born in Flushing Hospital and raised in Jackson Heights, a 35-

Nayeem had cased the room beforehand. His iPhone had spotty service inside Stuyvesant, and he wanted to be sure he’d have a signal. He tested the device in the second seat of the first row — he’d assumed he would be seated alphabetically — and it worked. He tried out the second seat counting from the other side of the room just to be safe — also good. Then he examined the sight lines to both seats from the teacher’s desk — what could the proctor see and not see? — and checked out the seats where he thought some of his friends would be sitting. One was right in front of the teacher. He made a note of that. That kid was out.

Nayeem had cheated on tests before. By his junior year, he and his friends had become fairly well-

5 Regents Exams are typically administered for three hours. After two hours, students who are done are allowed to leave. Nayeem is a good physics student. He worked his way through the test quickly, as he knew he would, finishing in an hour and a half. (He’d later learn he received a 97.) His plan had been to use the next half-

That day, however, there was a glitch. The proctor was someone Nayeem knew, Hugh Francis, an English teacher, and he was not just sitting at the desk but walking around the room. Francis even caught the girl next to Nayeem using her phone in the first few minutes of the test. While cell phones technically aren’t allowed in city schools, that rule was widely ignored at Stuyvesant. Many of the school’s students, some as young as 13, travel far from home, and their families insist on staying in touch. “Put it back in your pocket,” the proctor said, and the girl complied. It was all Nayeem could do to send a text to his friends: “Okay, I got you guys later.”

Nayeem had been writing the answers on a piece of scrap paper as he went along so he wouldn’t have to flip back and forth once he had the chance to text. He waited for the shift change. During a Regents Exam, two teachers share the proctoring duties, handing off the mantle at the 90-

He got bolder. Turning to page one of his completed exam, Nayeem lifted his phone just enough to snap a picture of that page, then put the phone down again. Over the next few minutes, he photographed the whole test booklet — all fifteen pages.

The night before, Nayeem had sent a group-

10 The next day, Nayeem used the same scheme during his U.S. history Regents Exam —only this time it was his turn to get help from others. He sat in the first seat of the first row, just a few feet from the proctor, and received the answers. Next, on June 18, came the Spanish Regents. Spanish was Nayeem’s weakest subject; he needed a score high enough to lift his final grade in the class out of the cellar (Regents are often factored into class grades at Stuyvesant). This time his plan was to take pictures of the questions, text them to friends who were facile with the language but not taking the test, then wait for his phone to vibrate with fully written paragraphs of Spanish.

About halfway through that test, just after the proctor switch, the school’s principal, Stanley Teitel, accompanied by a handful of other administrators, entered the exam room. A science teacher by background who still taught chemistry at the time, Teitel is tall and thin with a thick Brooklyn accent. As principal, he was known as an intense presence, liked personally but given to policies the students often found too restrictive. Teitel walked past Nayeem, then doubled back and stared down at him, taking him by surprise.

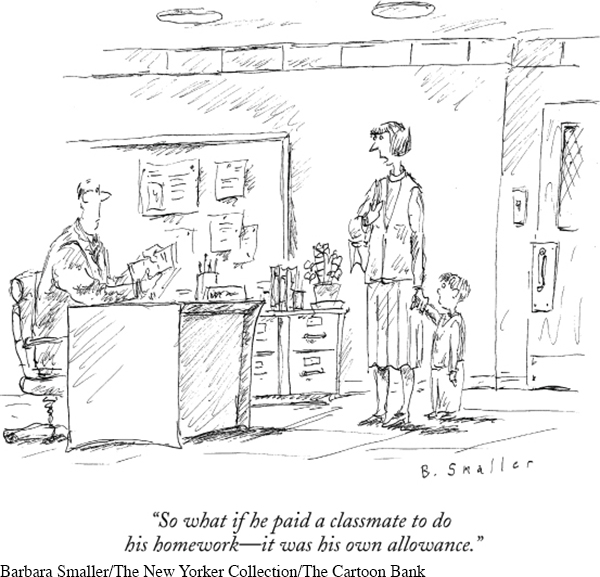

While the topic of this New Yorker cartoon is cheating, what is the artist suggesting about parents’ role in cheating? What might the teacher say in response to the parent?

“Do you have a phone?”

“Yeah,” Nayeem said.

“Give it to me.”

15 “Why?”

“Because,” Teitel said, “I’m the principal.”

Nayeem knew Teitel was aware he was cheating, although he wasn’t sure how Teitel found out. His best guess was that his answers on one of the earlier exams had been too similar to too many other students’ (he’d later learn that was true for the physics test). Nayeem’s phone not only had the recently incriminating texts and the names of those he’d been texting with on it, it still contained a record of every test he’d shared answers on since the start of the term. But there was no time to wipe the device clean. He had no choice now but to give it to Teitel.

Teitel escorted Nayeem to the front office, and instructed him to continue taking the test while Teitel and the others discussed how to proceed. Nayeem tried to calm himself with the thought that his phone was password-

The Stuyvesant scandal may have been the most notorious act of cheating to take place at a high school in the United States, but it is by no means the only high-

20 Around the country, there are other cases: In March, nine seniors just months from graduation from Leland High School, an acclaimed public school in San Jose, California, were accused of taking part in a cheating ring (one student was said to have broken in to at least two classrooms to steal test information before winter exams). In May, a high-

Eric Anderman, a professor of educational psychology at Ohio State University, has been studying cheating in schools for decades. He says research shows that close to 85 percent of all kids have cheated at least once in some way by the time they leave high school (boys tend to cheat a bit more than girls, although they might just be more likely to admit the transgression; otherwise, cheating is fairly uniform across demographic groups). Three months before Nayeem walked into his physics Regents Exam, the Stuyvesant Spectator, the school’s official student newspaper, happened to publish the results of a survey it conducted in which 80 percent of respondents (nearly two-

It’s impossible to determine whether the recent incidents reflect an uptick in the overall incidence of cheating (“It has been high, it continues to be high, and it’s extremely high now,” says Anderman). But the much-

The culture of sharing appears to also create fertile ground for cheating. It’s not just that e-

It’s tricky business to blame the Dick Fulds1 of the world for breeding a generation of cheaters, but Wall Street titans, politicians, and other high-

25 We now understand enough about brain science to blame biology as well. Modern research shows that the parts of the brain responsible for impulse control (measured in the lateral prefrontal cortex) may not completely develop until early adulthood, while the parts that boost sensation-

But why do bright kids — Stuyvesant and Harvard students — cheat? Aren’t they smart enough to get ahead honestly? One might think so, but the pressure to succeed, or the perception of it anyway, is often only greater for such students. Students who attend such schools often feel they not only have to live up to the reputation of the institution and the expectations that it brings, but that they have to compete, many of them for the first time, with a school full of kids as smart, or smarter, than they are. Harvard only admits so many Stuy students, Goldman Sachs will hire only so many Harvard kids. Competition can get ratcheted up to extreme levels. “Kids here know that the difference between a 96 and a 97 on one test isn’t going to make any difference in the future,” says Edith Villavicencio, a Stuyvesant senior. “But they feel as if they need the extra one point over a friend, just because it’s possible and provides a little thrill.”

Stuyvesant’s 2012 valedictorian, Vinay Mayar, talked about the pressure at the school in his graduation speech. Mayar, who lives on the Upper East Side and just started at MIT, called his classmates “a volatile mix of strong-

Teitel, Stuyvesant’s principal, used to like to share a quip with incoming freshmen: Grades, friends, and sleep — choose two. The work can be so demanding at top schools that students sometimes justify cheating as an act of survival, or rebellion even. At Harvard, the Crimson, which broke the story, reported that part of the take-

“Not everyone cheats, but it is collaborative,” says Daniel Solomon, a former Stuyvesant Spectator staffer who graduated in June, and is now starting at Harvard. “One of my friends told me, ‘School is a team effort.’ That’s sort of the ethos at Stuy.”

30 Some students rationalize cheating as a victimless crime — even an act of generosity. Sam Eshagoff, one of the students involved in the Long Island SAT scandal, justified taking the test at least twenty times, and charging others up to $2,500 per test to take the exam for them, by casting himself as a sort of savior. “A kid who has a horrible grade-

Nayeem and I meet for dinner on a weeknight in August at the Old Town pub, near Union Square. He says he decided to speak to me to tell his side of the story, and make his case for returning to Stuyvesant. His parents know about his decision, he told me later, but aren’t happy about it.

Nayeem speaks rapidly, and barely bothers with his food when it comes. He is wearing two bands on his wrist, one from the Stuyvesant Red Cross Club, another a hospital I.D. bracelet. Back in July, as news of the cheating scandal spread, he underwent a previously scheduled surgery, the removal of a benign tumor from his leg. “That was a real low point,” he says. “I was limping home with my parents. I was experiencing physical pain from the stitches. And people were contacting me on Facebook, asking ‘What’s gonna happen to the Regents?’” (Nayeem’s father, Najmul, had told a reporter that the tumor, along with a recent mugging, left Nayeem stressed and forced him to miss time at school. Those factors, he said, explained the cheating incident.)

Nayeem’s parents, he says, had always wanted him to go to Stuyvesant. Najmul publishes a small cultural Bangladeshi news-

Nayeem started studying for the city’s Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT), the gateway to the city’s elite public schools, two or three afternoons a week in the summer before seventh grade at a so-

35 Almost from his first day at Stuyvesant, Nayeem knew what GPA he’d need to maintain to have a shot at Harvard. “When you get into Stuy, they show you where the graduating seniors went to college and what grades they got,” Nayeem says. “You don’t get to see names, but you get to see their GPA in every subject and their SAT scores.” But the schoolwork was more difficult than Nayeem expected. He dreaded double-

By the end of the first term, Nayeem’s GPA hovered around 89 — solid, but not high enough for Harvard. He began staying up all night studying at friends’ houses. “My parents were a little tentative,” he says. “They’d rather I stay home, but they understood.” By the end of his second term, Nayeem had raised his GPA to 92. That’s when he says his biology teacher offered the class a deal: If everyone correctly completed their final Friday assignment, working through the weekend on it, she would raise everyone’s average by three points. “She knew there was this one guy who wouldn’t do it,” he says. “He never did a single homework or a single lab.”

But Nayeem wasn’t going to miss out on this chance for extra credit because of a slacker. On Friday night, he rushed and finished the homework. Then he put it up on Facebook as a note, tagging about fifteen of the kids in his class (he says he did it to lift the whole group up). It was, as he recalls, his first major act of cheating. He got caught and the class didn’t get the three points, but, he says, the teacher took mercy on him and didn’t turn him in.

When Nayeem began struggling in his sophomore year (trigonometry was especially hard for him), he started sharing — and borrowing —answers more. By junior year, when grades matter most to colleges, cheating had become a regular habit. “History had five teachers. I was getting tests for four of them. I was being nice to everyone, and they started helping me out.” By now he realized “how lazy teachers could be. I studied for the first test. But I looked at the new test and last year’s test and they were, like, 75 percent the same exact questions and the same exact answers. So I was like, ‘Okay, why am I studying?’ ”

Some teachers teach not just the same subject but the same class for three or four different periods over the course of a day. Nayeem began passing test answers from the early classes to the later ones. He knew he was taking a risk, but he also knew he hadn’t officially been caught yet, not even for a first offense. (At Stuyvesant, a first cheating incident triggers a warning, and a second goes on your permanent record, which compels you to answer yes when asked on college applications if you’ve ever cheated.) Nayeem’s rationale for who he did and didn’t share answers with was byzantine. “There’s kids you know, and there’s kids you really know. There are kids I trust a lot and kids I care about. There are kids I really don’t care too much about, but I want them to have a bright future. There are kids that can help me in the future. There are kids that are good at most subjects, but they suck at one, and I worked that to my advantage.”

40 Nayeem remembers wondering before the physics Regents if it was worth it to put so much time into cheating on such an easy test. But he decided it was — especially considering the help he could use on the Spanish test. Studying, he says, seemed pointless. “It’s not like studying is going to change one point on my exam,” he says, “because there are things I am bound to not know.” He says he thought about it morally, too. “I was like, ‘There’s a ton of kids that are studying so hard, and here’s 140 kids that are just going to ace the exam without knowing shit, right?’ But a good number of people at Stuy have asked me for some kind of help.”

The only reason he got caught, he says, was that “it was too many people with one exam. It got really big, much faster than I thought it would. One day it was 5 people, and one day it was 140.”

Stanley Teitel told Nayeem right away that he couldn’t return to Stuyvesant in the fall, but Nayeem had all summer to fight that decision, which he did. Since last March, ironically enough, he’s been working teaching kids at a test-

Nayeem’s identity might never have become public knowledge if a friend hadn’t tried to help him by circulating a petition online to try to convince the school not to expel him. “He told me, ‘There’s a lot of people that do a lot worse in Stuy. There’s people that smoke weed, people that do drugs. True, it’s unethical, it’s an extreme breach of academic integrity, and it’s at an elite school. It is bad, but I don’t get how kicking you out would help anything.’” The DOE had previously acknowledged it was investigating the incident, but the petition exposed the scandal, and outed Nayeem.

Shortly after Nayeem got caught, he went home and remotely wiped his phone of its data; the school and the DOE aren’t commenting, but Nayeem has implied that they didn’t get the names of all 140 recipients of his text message before that. Initial press reports held that the school had 92 names. Later that number drifted down to 72, and more recently to 66. A few of those 66 students were cleared owing to lack of evidence. While at first it seemed that only a handful of the remaining accused students would be suspended, the DOE announced earlier this month that all 66 would be suspended — a dozen for up to ten days and the rest for up to five days, depending on what each of them has to say in a one-

45 Nayeem says he feels bad about what may happen to the kids who are being punished. “I don’t want them to go to lousy colleges because of this.” But he insists his friends aren’t upset with him. “I’ve done a lot for these people, so much so that they know I have got good intentions.” He says his parents go back and forth about what happened. “Sometimes they’re mad at me. Sometimes they’re sad. Sometimes they’re very optimistic.”

Nayeem says he is ready to accept any punishment the DOE throws at him as long as he is able to go back to Stuyvesant. The worst damage, he argues, has already been done — a simple Google search will ruin him in the eyes of any college-

On August 3, Stanley Teitel resigned from Stuyvesant, saying in a letter that it was “time to devote my energy to my family and personal endeavors.” Teitel’s critics say he pushed kids too hard. “He saw the students’ stress as a sign that the school was doing what it was supposed to be doing,” says one teacher. Another calls him “a visionless bureaucrat who is sort of like, ‘Well, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. And we know it ain’t broke because everyone’s doing such a good job getting into college.’” His defenders note that he did more than most administrators to curb cheating, and caught Nayeem.

The new interim principal, Jie Zhang, is a Chinese-

While many Stuyvesant parents are outraged by the scandal, some seem to think the school has been unfairly vilified. In terms of cheating, Stuyvesant “is no different from Horace Mann or Bronx Science,” one father says. Many of the students who were not implicated, meanwhile, feel betrayed by Nayeem and his confederates. “All the people I talked to said [Nayeem] deserved to be expelled,” says one student. “They said they were angry taking the tests knowing other people were cheating it.”

50 As for Harvard, the probe there is expected to continue well into the fall and perhaps even beyond, with each student’s situation being adjudicated individually. “It will take as long as it will take,” says Harvard spokesman Jeff Neal. “We are committed to ensuring the students involved have their due-

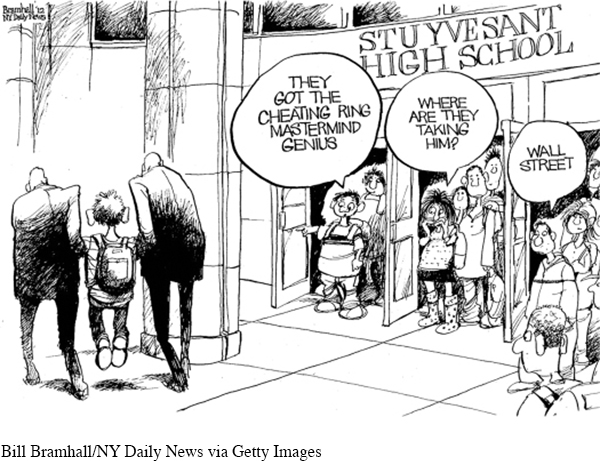

What connection are both Kolker and the artist in this editorial cartoon making between Wall Street and the Stuyvesant cheating scandal?

As of this writing, Nayeem has been sitting out the start of the school year, not yet enrolling at another high school in hopes that the DOE will relent and allow him to return to Stuyvesant. He’s hopeful, but far from confident, that will happen. When he visited other schools with an eye toward transferring, Nayeem says, his heart sank. “I just wanted to stay at Stuy more. Now I realize, but before I didn’t — you’re so lucky to go to Stuy. You’re able to learn. In other schools, there are kids in school who are texting during the day while the teacher’s talking. There’s no learning. It would have been easier, but it wouldn’t have been what I wanted.”

When I ask him if he thinks he’d be able to handle the workload at Stuyvesant without cheating, he doesn’t hesitate. “I can definitely study my way out of it. Like, now that my future’s on the line.”

But he says he still wonders if maybe he could have gotten away with his cheating scheme if he spent more time organizing it, or put more locks on his phone. At times, it seems, he’s still trying to rationalize what he did. He says he didn’t think the Regents was as big a deal as the SAT. “I didn’t know I could have gotten kicked out of Stuy if I pulled this off. That was never made clear to me.”

This stops me. He cheated on not just one but three different Regents Exams, and he didn’t think that could get him kicked out of high school?

55 Nayeem squints. “I mean, like, I really didn’t think so.” Then he sits up straighter. “And now it’s like a second chance. It’s like a second chance that has a lot of dark clouds. It still has consequences, right? I was still suspended. I still won’t be able to go to a decent college. But hopefully I’ll be able to go somewhere. That’s what I’m worried about. Somewhere decent enough to work my way up into a career.”

What career?

“I want to be an investment banker.”

Understanding and Interpreting

What is a conclusion that you could draw, according to Carol Dweck, who is cited in paragraph 22, about the effect that standardized testing may have on cheating?

What is the “culture of sharing” that Kolker identifies in paragraph 23, and what role does it play in how today’s students define cheating?

Kolker includes quotes from people who essentially rationalize the cheating. What are the arguments that those people put forward?

Does Kolker seem to believe that the steps the new principal of Stuyvesant has taken will have any effect on cheating at the school (par. 48)? Why or why not? Use evidence from the text to support your argument.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

How does Kolker give the reader the impression that Nayeem’s cheating was premeditated? What effect does this have on his argument about cheating?

How valid is the evidence that Kolker provides in support of the following factors that also might influence students’ decisions to cheat?

social norms

biology

competition

How does Kolker create suspense in the events leading up to Nayeem’s being caught?

What is Kolker’s purpose in moving away from Stuyvesant to describe other cheating scandals (pars. 19–

20)? Why does he place that section there, instead of at the beginning of the piece? Reread the last few paragraphs of the article, starting with “As of this writing” (par. 51). Though he never explicitly says, what do you think Kolker’s feelings are about Nayeem and his actions? Point to specific evidence from this section to support your response.

The final sentence of the article is Nayeem’s statement that he wants to be an investment banker in the future. What is the effect of this ending?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

During the testing, Stuyvesant principal Teitel seized Nayeem’s phone and accessed his messages, likely without Nayeem’s consent. Were Teitel’s actions legal? Were they justified? Were they ethical? Conduct research on the Supreme Court decision New Jersey v. T.L.O. (1985), which is the case that has set the precedent for school search and seizures, to support your response.

Kolker offers several possible reasons why students cheat—

rise of the importance of standardized tests, the culture of sharing, social factors, biology of adolescent brains, and the competitive nature of school. Which reasons do you think are most valid from your own experience? Why? What are other factors that he does not identify that might play a role? Near the end of the article, Nayeem says, “I didn’t know I could have gotten kicked out of Stuy if I pulled this off. That was never made clear to me” (par. 53). Locate your own school’s academic honesty policies. What are the consequences for cheating at your school? Have you or anyone you know ever been disciplined for cheating? Why or why not? What changes would you recommend to your school’s policies?

After Nayeem was expelled from Stuyvesant, over two hundred students signed the petition below to have him reinstated. Would you have signed? Why or why not?

To:

Stuyvesant High School Administration, Attn: Principal Teitel

I just signed the following petition addressed to: Stuyvesant High School Administration.

-----------

Reinstate Nayeem Ahsan as a student at Stuyvesant

Nayeem Ahsan is a valued member of the Stuyvesant community. He plays an integral role in school morale, photographing all major school events among the countless other selfless deeds he’s done for the class of 2013. His absence would leave the senior class of 2013 defunct. Expulsion from his home for the last three years is an exorbitant repercussion for his mistake, Nayeem does not deserve to have his future ripped out of his hands, simply so the administration can set an example.

-----------

Sincerely,

[Your name]