7.16

Why We Look the Other Way

Chuck Klosterman

Chuck Klosterman (b. 1972) is an American writer who publishes essays on music, sports, and pop culture. He is a regular contributor to the sports-

Shawne Merriman weighs 272 pounds. This is six pounds less than Anthony Muñoz, probably the most dominating left tackle of all time. Shawne Merriman also runs the 40-

You do not need Mel Kiper’s1 hard drive to deduce what these numbers mean: As an outside linebacker, Shawne Merriman is almost as big as the best offensive tackle who ever played and almost as fast as the best wide receiver who ever played. He is a rhinoceros who moves like a deer. Common sense suggests this combination should not be possible. It isn’t.

In this photo, we see a typical football hit, but when frozen in a shot, we can see the violence of the impact between two very large and strong men.

Merriman was suspended from the San Diego Chargers for four games last season after testing positive for the anabolic steroid nandrolone. He argues this was the accidental result of a tainted nutritional supplement. “I think two out of 10 people will always believe I did something intentional, or still think I’m doing something,” Merriman has said. If this is truly what he believes, no one will ever accuse him of pragmatism. Virtually everyone who follows football assumes Merriman used drugs to turn himself into the kind of hitting machine who can miss four games and still lead the league with 17 sacks. He has been caught and penalized, and the public shall forever remain incredulous of who he is and what he does.

5 The public knows the truth, or at least part of it. And knowing this partial truth, the public will return to ignoring this conundrum almost entirely.

The public will respond by renewing its subscription to NFL Sunday Ticket, where it will regularly watch dozens of 272-

As a consequence, you will have to make some decisions.

Not commissioner Roger Goodell.

You.

10 On Feb. 27, federal, state and local authorities seized the records of an Orlando pharmacy, accusing the owners of running an online bazaar for performance-

None of this is particularly shocking.

But then there is the case of Richard Rydze. In 2006 Rydze, an internist, purchased $150,000 of testosterone and human growth hormone from the Florida pharmacy over the Internet. This is not against the law. However, Rydze is a physician for the Pittsburgh Steelers. He says he never prescribed any of those drugs to members of the team, and I cannot prove otherwise. However, the Steelers have had a complicated relationship with performance enhancers for a long time. Offensive lineman Steve Courson (now deceased) admitted he used steroids while playing for Pittsburgh in the 1970s and early ’80s, as did at least four other guys. Former Saints coach Jim Haslett, a player in Buffalo from 1979 to 1985, has said the old Steelers dynasty essentially ran on steroids. The team, obviously, denies this.

Several members of the Carolina Panthers’ 2004 Super Bowl team were implicated in a steroid scandal involving Dr. James Shortt, a private practitioner in West Columbia, S.C. One of these players was punter Todd Sauerbrun. Do not mitigate the significance of this point: The punter was taking steroids. The punter had obtained syringes and injectable Stanozolol, the same chemical Ben Johnson used before the 1988 Olympics. I’m not suggesting punters aren’t athletes, nor am I overlooking how competitive the occupation of punting must be; I’m merely pointing out that it’s kind of crazy to think punters would be taking steroids but defensive tackles would not. We all concede that steroids, HGH and blood doping can help people ride bicycles faster through the Alps. Why do we even momentarily question how much impact they must have on a game built entirely on explosion and power?

“People may give a certain amount of slack to football players because there’s this unspoken sense that in order to play the game well, you need an edge,” USC critical studies professor Todd Boyd told the Los Angeles Times last month. Boyd has written several books about sports, race and culture. “That’s what people want in a football player — someone who’s crazy and mean.”

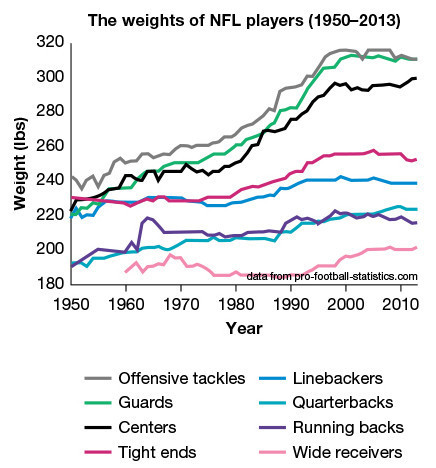

Looking over the information presented in this chart about the weight of NFL players, what is a conclusion that you can draw that would support or contradict Klosterman’s argument about the use of PEDs?

15 It’s a subtle paradox: People choose to ignore the relationship between performance enhancers and the NFL because it’s unquestionably the league where performance enhancers would have the biggest upside. But what will happen when such deliberate naïveté becomes impossible? Revelatory drug scandals tend to escalate exponentially (look at Major League Baseball and U.S. track and field). Merriman, Sauerbrun and the other 33 players suspended by the NFL since 2002 could be exceptions; it seems far more plausible they are not. We are likely on the precipice of a bubble that is going to burst. But if it does, how are we supposed to feel about it? Does this invalidate the entire sport, or does it barely matter at all?

This is where things become complicated.

It can be strongly argued that the most important date in the history of rock music was Aug. 28, 1964. This was the day Bob Dylan met the Beatles in New York City’s Hotel Delmonico and got them high.

Obviously, a lot of people might want to disagree with this assertion, but the artistic evidence is hard to ignore. The introduction of marijuana altered the trajectory of the Beatles’ songwriting, reconstructed their consciousness and prompted them to make the most influential rock albums of all time. After the summer of 1964, the Beatles started taking serious drugs, and those drugs altered their musical performance. Though it may not have been their overt intent, the Beatles took performance-

Jack Kerouac wrote On the Road on a Benzedrine binge, yet nobody thinks this makes his novel less significant. A Wall Street stockbroker can get jacked up on cocaine before going into the trading pit, yet nobody questions his bottom line. It’s entirely possible that you take 10mg of Ambien the night before a big day at the office, and then drink 32 ounces of coffee when you wake up (possibly along with a mind-

20 My point is not that all drugs are the same, nor that drugs are awesome, nor that the Beatles needed LSD to become the geniuses they already were. My point is that sports are unique in the way they’re retrospectively colored by the specter of drug use. East Germany was an Olympic force during the 1970s and ’80s; today, you can’t mention the East Germans’ dominance without noting that they were pumped full of Ivan Drago–

Now, the easy rebuttal to this argument is contextual, because it’s not as if Roger Waters was shooting up with testosterone in order to strum his bass-

I am told we live in a violent society. But even within that society, football players are singular. Another former Eagle, strong safety Andre Waters, committed suicide last November at age 44. A postmortem examination of his brain indicated he had the neurological tissue of an 85-

Announcers casually lionize pro football players as gladiators, but that description is more accurate than most would like to admit. For the sake of entertainment, we expect these people to be the fastest, strongest, most aggressive on earth. If they are not, they make less money and eventually lose their jobs.

This being the case, it seems hypocritical to blame them for taking steroids. We might blame them more if they did not.

25 Around this time last year, I wrote an essay for [ESPN] The Magazine about Barry Bonds — specifically, how steroids made his passing of Babe Ruth on the career home run list problematic. I still believe this to be true, just as I believe that the notion of an NFL that’s more juiced than organic is more negative than interesting. It would be easier to be a football fan if none of this was going on. But since it is going on, we will all have to decide how much this Evolved Reality is going to bother us.

This will not be simple. I don’t think there will be a fall guy for the NFL; over time, we won’t be able to separate Merriman from the rest of the puzzle (which MLB has so far successfully done with Bonds). It won’t be about the legitimacy of specific players. This will be more of an across-

The answer depends on who you are. And maybe how old you are.

In 1982, I read a story about Herschel Walker in Sports Illustrated headlined “My Body’s Like an Army.” It explained how, at the time, Walker didn’t even lift weights; instead, he did 100,000 sit-

But I was 10 years old.

30 There comes a point in every normal person’s life when they stop looking at athletes as models for living. Any thinking adult who follows pro sports understands that some people are corrupt and the games are just games and money drives everything. It would be strange if they did not realize these things. But what’s equally strange is the way so many fans (and sportswriters, myself included) revert back to their 10-

Most of the time, we don’t care what football players do when they’re not playing football. On any given Wednesday, we have only a passing interest in who they are as people or how they choose to live. But Sunday is different. On Sunday, we have wanted them to be superfast, superstrong, superentertaining and, weirdly, superethical. They are supposed to be pristine 272-

It may be time to rethink some of this stuff.

Understanding and Interpreting

Klosterman is not making a simplistic argument about performance-

enhancing drugs here. He is not, for instance, simply suggesting that PEDs should be banned in football. What is his central claim about the relationship between the football players and the viewers of the NFL? In two different places, Klosterman uses the phrase “Evolved Reality” (pars. 6 and 25). What does this phrase mean, and what purpose does it serve in this argument?

The references to Bob Dylan, the Beatles, Jack Kerouac, and Pink Floyd are likely included here as counterarguments to the idea that PEDs are always automatically bad. Explain the conclusion the reader is expected to draw from these references and evaluate how well they support Klosterman’s overall claim. Do they really work as counterarguments?

Throughout the piece, Klosterman compares the use of PEDs in football and in baseball. What are the significant differences that he identifies, and how do these differences support his overall claim about PEDs in sports?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What is a likely reason that Klosterman started his argument with a description of Shawne Merriman’s size and speed? What is a reader expected to conclude from the first three paragraphs?

Since this article appeared in ESPN The Magazine, we can assume that Klosterman’s audience is made up of sports fans. What words, phrases, and allusions does Klosterman include that make it clear that this is his intended audience? What might he have included if he were writing for an audience not as familiar with sports?

Evaluate Klosterman’s logical reasoning in paragraph 12. What evidence does he include? Where does he make unsupported assumptions? Where does he commit logical fallacies? What are his biases? Overall, how effective is this paragraph in supporting his position?

In paragraph 23, Klosterman uses the word “gladiators” to describe NFL players. What are the positive and the negative connotations of this word, and how do these conflicting meanings help illustrate Klosterman’s claim?

Klosterman saves his story about how his ten-

year- old self admired Herschel Walker until the end of his piece (pars. 28– 29). What purpose does this section serve in his argument, and why is it most effective— or not— at the end of the piece? A rhetorical question is a device that authors use in which they pose a question for the purpose of trying to make a point. Klosterman uses this device regularly throughout this piece. Identify one or two examples and explain the point the question helps Klosterman make.

Reread the last three paragraphs. What is Klosterman’s tone toward NFL players and viewers? How does this tone reflect his central claim?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

There are several issues that Klosterman raises in this piece: use of PEDs, dangers of concussions and injury in sport, recreational drug use by musicians and writers, and the ethical decisions facing sports fans. Choose one of these topics and write an argument in which you explain why you support, challenge, or qualify the conclusion that Klosterman draws.

Think about yourself as a fan. You might not like to watch sports like Klosterman does, but you likely are a fan of specific celebrities, musicians, authors, actors, and so on. Explain the positive and negative aspects of your relationship with them. What are the costs and benefits of your fandom, to those you watch and to yourself?

Choose an athlete who has been caught or accused of using PEDs. Research the types of drugs he or she may have been using and how the drugs helped, and explain to what extent the athlete behaved unethically.

If they are adults and are informed about the potential health risks, should athletes be allowed to take whatever PEDs they want as long as they identify exactly what drugs they take? Choose a sport or another form of competition and write an argument about what types of benefits should be allowed or prohibited under the governing rules for that sport or competition.

While Klosterman focuses mostly on PEDs that allow athletes to become faster and stronger, there is another class of PEDs, known as beta blockers, that has also been banned from many athletic competitions. This category includes drugs that decrease the anxiety that people can feel in pressure situations such as competitive pistol shooting. Read the following excerpt from an article by Carl Elliot, “In Defense of the Beta Blocker,” and explain why you think that such drugs should be legal or not in competitive sports.

So the question for pistol shooting is this: should we reward the shooter who can hit the target most accurately, or the one who can hit it most accurately under pressure in public? Given that we’ve turned big-

time sports into a spectator activity, we might well conclude that the answer is the second— it is the athlete who performs best in front of a crowd who should be rewarded. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that that athlete is really the best. Nor does it mean that using beta blockers is necessarily a disgrace in other situations. If Barack Obama decides to take a beta blocker before his big stadium speech at the Democratic Convention next week, I doubt his audience will feel cheated. And if my neurosurgeon were to use beta blockers before performing a delicate operation on my spine, I am certain that I would feel grateful.