7.18

Is Human Enhancement Cheating?

Brad Allenby

Braden R. Allenby (b. 1950) is the director of the Center for Earth Systems Engineering and Management at Arizona State University and Lincoln Professor of Engineering and Ethics. He is a regular contributor on science and technology matters for Slate, an online magazine. This article was published in the May 9, 2013, issue of Slate.

KEY CONTEXT In 2012, Lance Armstrong was stripped of his seven wins of the Tour de France cycling competition due to his acknowledgment of using illegal performance-

Were you incensed when Lance Armstrong was finally cornered and stripped of his seven Tour de France titles? Almost everyone seemed to be. While some felt he had been treated unfairly, most appeared to feel betrayed by a cheater in whom they had believed. In 2013, neither Barry Bonds nor Roger Clemens made the Baseball Hall of Fame, even with their clearly superior records, because they used steroids. This was despite the fact that, as a New York Times editorial put it, the Hall of Fame is hardly a Hall of Virtue, filled as it is with “lowlifes, boozers and bigots.” Steroid use is apparently a different level of sin: It is cheating.

In another area, however, the American Society for Plastic Surgeons reported that in 2011 Americans spent $11.4 billion on cosmetic surgery and underwent 13.8 million procedures (figures exclude reconstructive surgery). No allegations of cheating in that arena — or, apparently, even slowing down.

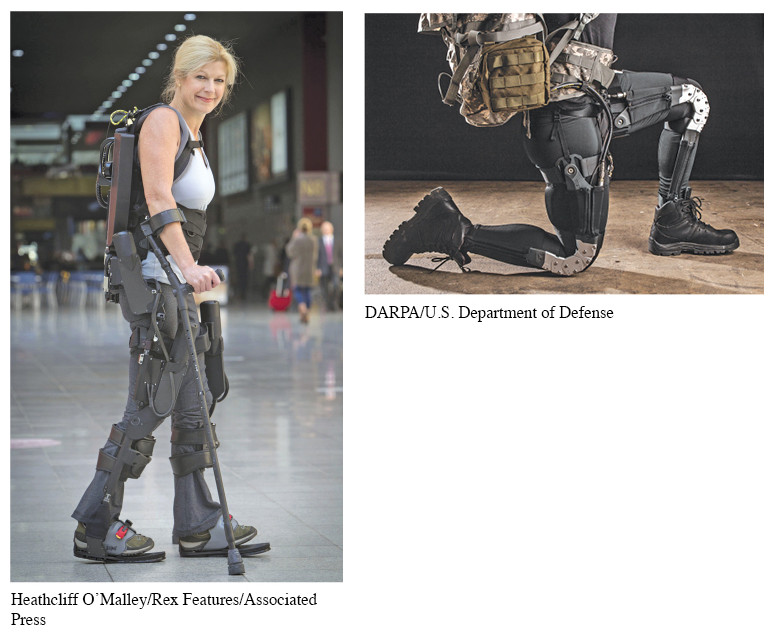

In yet a different domain, campaigners are increasingly concerned by the possibility of enhanced military “superwarriors,” especially as technologists strive to separate the soldier from immediate conflict areas — as, for example, unmanned aircraft systems (commonly called drones) do now. Meanwhile, autonomous robots and human/robot hybrids connected by powerful computer-

Probably few people would have objections to these exoskeletons to help disabled people to walk and function fully, but what are the ethical lines that could be drawn for their use in other areas, such as in warfare or sports competitions, or even in their use in jobs that require physical force?

We are deeply conflicted when it comes to human enhancement technologies. It is unclear, for example, precisely whom Armstrong was cheating. Enhancing has been pervasive in cycling for many years, and when he was stripped of his Tour de France titles, they were not awarded to anyone else because . . . well, everyone else was also under “a cloud of suspicion,” as the Union Cycliste Internationale put it. So he was not cheating his competitors, or at least not completely. And if just breaking rules —which he, and apparently some of his peers, were doing — is cause for substantial retribution, traffic speeders across the country, and those of you who just “borrowed” that pen from work, are in deep trouble.

5 Surgical enhancement of various body parts, on the other hand, does not appear to be regarded as cheating. False allure is apparently caveat emptor. (And are you really going to ban cosmetics?)

Questions of the impact of enhancement technologies on the psychology of conflict, especially in counterinsurgency environments, are complex. But arguments that it’s cheating to use technology to distance soldiers from potential harm are weak. War has rules, but it is not a sport, and the idea that an individual should be exposed to maiming or death out of some misplaced demand for “fairness,” as if war were a soccer game, is difficult to defend.

That doesn’t mean we can’t draw some conclusions from this confusion. First, “cheating” does not seem to be an issue of enhancement generally. People seem fine with personal enhancement, especially where the practice is long-

People get queasy, however, when human enhancement shifts from the quotidian to the highly symbolic. Major professional sports, for example, have long been dominated by commercial ethics, money, and entertainment dollars, and few indeed are the athletic stars who cannot be lured elsewhere by money. Professional teams and sports heroes, however, are not seen as simply part of the commercial entertainment enterprise. Rather, in an increasingly complex and unstable age, sports events and stars become not just symbols of city and home but a part of personal identity. Look at the visceral outrage that Clevelanders expressed when a local star, LeBron James, left for Miami rather than staying in Cleveland. That’s not about contract or business; that’s something going on at a far deeper level. More poignantly, it is remarkable how the healing of Boston after the recent bombing is entwining the Boston Red Sox, the Celtics, and the Bruins.

Moreover, sports are still iconic for purity, for the simplicity of an idyllic earlier America (which even a fleeting brush with history tells us is illusory). Look, for example, at the frequency with which the myth of the “student-

10 Military human enhancements seem to occupy a middle ground. There is unquestionably some concern about what human enhancements in this domain might come to, especially if one moves beyond temporary enhancements like pharmaceuticals to more permanent enhancements, such as genetic engineering. The concerns here go beyond the operational. If enhanced humans leave the military and return to civilian life, for instance, what will happen? The differences may be subtle — genetic engineering enabling one to see in the dark, or providing maximum muscle development and efficiency, or augmented cognitive and neural performance, for example. Or they may be less so — one might have a set of personal technologies that are accessed by onboard computer-

What does all this mean? It means that social responses to human enhancement are more nuanced and complex than is usually recognized. More specifically, it means that the same enhancement will generate different responses depending on the domain in which it is introduced. If one wants to promote an enhancement, making it available and familiar to the public might be an excellent strategy. A military use that doesn’t trigger sci-

From a social perspective, however, perhaps the most important observation is that to the extent an enhancement technology has symbolic dimensions, it will be very difficult to evaluate rationally and objectively. The risk is that various enhancement technologies are regulated or rejected not based on a realistic assessment of their costs and benefits, but because of how they were introduced, in sports or in doctors’ offices. The challenge, then, is not “cheating” but the far more difficult challenge of developing the ability to interact ethically, rationally, and responsibly with the world of enhancement technologies that is already here.

Understanding and Interpreting

What can you conclude about the author’s opinion of Lance Armstrong’s actions? To what extent does Allenby seem to think Armstrong cheated? Explain your answer using evidence from the article.

Explain what Allenby means when he says “We are deeply conflicted when it comes to human enhancement technologies” (par. 4).

Create a line graph to illustrate how Allenby identifies the general public’s acceptance of the various human enhancements he describes in this piece. Plot your graph on a scale from “Fully accepted” to “Unacceptable.”

According to Allenby, why do some people react so emotionally when they hear about cheating in sports, as opposed to other human enhancements, such as cosmetic surgery?

What are the pros and cons of the “superwarrior” that Allenby describes (par. 3)?

Reread the last paragraph and summarize Allenby’s conclusion about what is most important for the general public to understand about human-

enhancement technologies.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Even though Allenby begins by asking if readers had an emotional reaction to the news of Lance Armstrong’s use of performance-

enhancing drugs, most of his argument relies on his use of logos. Review the article carefully and explain how he uses rhetorical appeals to build his argument. Page 506Allenby uses a term in this piece—

“superwarriors”—to describe soldiers who use human- enhancement technologies (par. 3). How does his use of this term reflect his tone toward the issue of “cheating”? Allenby utilizes a very complex organizational structure in this piece. Notice how often he juxtaposes sports, the military, and other areas of human enhancement. Identify one significant place where he puts two topics near each other and explain how this juxtaposition helps to support his argument or to illustrate a point he is trying to make.

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

According to Allenby, Lance Armstrong “was not cheating his competitors” and was “just breaking rules” (par. 4). Based on what you know about Armstrong, why do you agree or disagree with this assertion?

Allenby is fairly broad in his initial definition of “human enhancement,” including socially accepted changes, such as plastic surgery, vaccines, and joint replacements, but there are many other types of enhancements that he does not mention. Adderall, for instance, is a drug that is often prescribed to people diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) but is also used by some students as a study aid. In a March 2013 opinion piece in the New York Times, Roger Cohen states, “Adderall has become to college what steroids are to baseball: an illicit performance enhancer for a fiercely competitive environment.” Conduct brief research on Adderall and write an argument about whether it should be banned for students taking tests like the SAT, ACT, or other high-

stakes assessments, the scores for which are compared to those of other students for college entrance. Use evidence from your research to support your position and explain whether Allenby would agree or disagree. When discussing human enhancements in the military, Allenby seems to suggest that military leaders need to think carefully about the language they use when naming their technologies, avoiding terms such as “killer robot.” Think about some current technologies that have particularly effective names. What makes those names so effective? Then, consider how some technologies could be either enhanced or hindered by having a different name. Propose new names for these products and explain the effect of the new name. You might go so far as creating a whole new brand, including a logo, packaging, an advertisement, etc.