7.3

Part 2 The Case against Perfection

The ethic of giftedness, under siege in sports, persists in the practice of parenting. But here, too, bioengineering and genetic enhancement threaten to dislodge it. To appreciate children as gifts is to accept them as they come, not as objects of our design or products of our will or instruments of our ambition. Parental love is not contingent on the talents and attributes a child happens to have. We choose our friends and spouses at least partly on the basis of qualities we find attractive. But we do not choose our children. Their qualities are unpredictable, and even the most conscientious parents cannot be held wholly responsible for the kind of children they have. That is why parenthood, more than other human relationships, teaches what the theologian William F. May calls an “openness to the unbidden.”

25 May’s resonant phrase helps us see that the deepest moral objection to enhancement lies less in the perfection it seeks than in the human disposition it expresses and promotes. The problem is not that parents usurp the autonomy of a child they design. The problem lies in the hubris of the designing parents, in their drive to master the mystery of birth. Even if this disposition did not make parents tyrants to their children, it would disfigure the relation between parent and child, and deprive the parent of the humility and enlarged human sympathies that an openness to the unbidden can cultivate.

To appreciate children as gifts or blessings is not, of course, to be passive in the face of illness or disease. Medical intervention to cure or prevent illness or restore the injured to health does not desecrate nature but honors it. Healing sickness or injury does not override a child’s natural capacities but permits them to flourish.

Nor does the sense of life as a gift mean that parents must shrink from shaping and directing the development of their child. Just as athletes and artists have an obligation to cultivate their talents, so parents have an obligation to cultivate their children, to help them discover and develop their talents and gifts. As May points out, parents give their children two kinds of love: accepting love and transforming love. Accepting love affirms the being of the child, whereas transforming love seeks the well-

These days, however, overly ambitious parents are prone to get carried away with transforming love — promoting and demanding all manner of accomplishments from their children, seeking perfection. “Parents find it difficult to maintain an equilibrium between the two sides of love,” May observes. “Accepting love, without transforming love, slides into indulgence and finally neglect. Transforming love, without accepting love, badgers and finally rejects.” May finds in these competing impulses a parallel with modern science: it, too, engages us in beholding the given world, studying and savoring it, and also in molding the world, transforming and perfecting it.

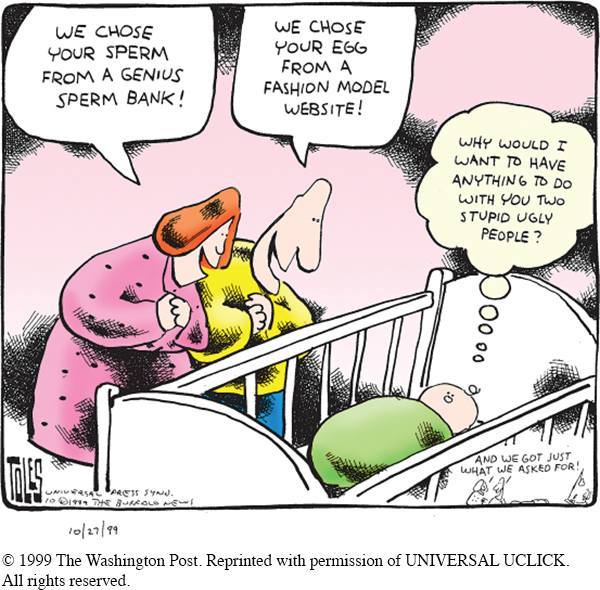

This political cartoon by Tom Toles appeared in 1999.

The mandate to mold our children, to cultivate and improve them, complicates the case against enhancement. We usually admire parents who seek the best for their children, who spare no effort to help them achieve happiness and success. Some parents confer advantages on their children by enrolling them in expensive schools, hiring private tutors, sending them to tennis camp, providing them with piano lessons, ballet lessons, swimming lessons, SAT-

30 The problem with genetic engineering is that [it] represent[s] the one-

From a religious standpoint the answer is clear: To believe that our talents and powers are wholly our own doing is to misunderstand our place in creation, to confuse our role with God’s. Religion is not the only source of reasons to care about giftedness, however. The moral stakes can also be described in secular terms. If bioengineering made the myth of the “self-

In a social world that prizes mastery and control, parenthood is a school for humility. That we care deeply about our children and yet cannot choose the kind we want teaches parents to be open to the unbidden. Such openness is a disposition worth affirming, not only within families but in the wider world as well. It invites us to abide the unexpected, to live with dissonance, to rein in the impulse to control. A Gattaca-like world in which parents became accustomed to specifying the sex and genetic traits of their children would be a world inhospitable to the unbidden, a gated community writ large. The awareness that our talents and abilities are not wholly our own doing restrains our tendency toward hubris.

Though some maintain that genetic enhancement erodes human agency by overriding effort, the real problem is the explosion, not the erosion, of responsibility. As humility gives way, responsibility expands to daunting proportions. We attribute less to chance and more to choice. Parents become responsible for choosing, or failing to choose, the right traits for their children. Athletes become responsible for acquiring, or failing to acquire, the talents that will help their teams win.

A lively sense of the contingency of our gifts — a consciousness that none of us is wholly responsible for his or her success — saves a meritocratic society from sliding into the smug assumption that the rich are rich because they are more deserving than the poor. Without this, the successful would become even more likely than they are now to view themselves as self-

35 There is something appealing, even intoxicating, about a vision of human freedom un-

Understanding and Interpreting

In this final section, what is Sandel’s view of how bioengineering and genetic enhancement “threaten to dislodge” the “ethic of giftedness” in parenting (par. 24)?

Sandel explains William F. May’s distinction between the “accepting love” and “transforming love” (par. 27) that parents give their children. Which of these types of love does Sandel believe is most jeopardized by genetic enhancement?

What does Sandel mean by “the hubris of the designing parents” (par. 25)? To what extent do you think Sandel is imposing a value judgment on parents who would consider genetically engineering their children?

Sandel raises the issue of parents who endeavor to help their children become successful by providing SAT tutors or private coaching in sports and asks whether these efforts are different from genetic enhancement (pars. 29–

32). How does he answer that question? Do you agree or disagree? How does Sandel answer the question he asks in paragraph 30: “What would be lost if biotechnology dissolved our sense of giftedness?” Consider the language he uses to frame his response, including “moral stakes” and “secular terms” (par. 31).

What does Sandel mean when he asserts that the “real problem” with genetic enhancement “is the explosion, not the erosion, of responsibility” (par. 33)?

Why does Sandel question the impact of genetic engineering on a “meritocratic’ society” (par. 34)? Why is this specific context relevant to his viewpoint?

What is Sandel’s final conclusion about genetic enhancement? Does he qualify his earlier position or reassert it?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

As Sandel explores the concept of “giftedness,” he alludes to the theologian William F. May’s phrase “openness to the unbidden” (pars. 24 and 25). To what extent does using May as a source strengthen or weaken the argument Sandel is in the process of developing?

What counterarguments does Sandel cite in this section? How effective is he in refuting them? Comment on at least two examples of counterarguments.

What is the logic that Sandel uses to develop his point that genetically engineering children would undermine or “transform” our sense of “humility” and “solidarity” (par. 31)? Does he move from a series of examples to a general conclusion or the reverse: that is, from a general statement to a series of examples that support it?

In this section, Sandel refers to “a religious standpoint,” and in the previous section he refers to the “pro-

life” position on abortion (par. 14). Issues of religion and abortion can sometimes be volatile and evoke strong reactions. How does he maintain a balanced perspective on these issues? Consider both his language and organization. Page 425When Sandel argues against “a world inhospitable to the unbidden,” he uses the metaphor that our world would risk becoming “a gated community writ large” (par. 32). What does that figure of speech suggest? To what extent do you think it is an effective strategy to promote his argument?

In paragraph 34, Sandel moves to a more political discussion of income inequity. Do you think he connects that issue clearly to the larger topic, or does it seem tangential or forced? Explain in terms of the argument he is developing.

How would you describe the tone of the conclusion to this essay? Is Sandel optimistic or pessimistic? Is he guarded or emphatic? Cite specific language choices to support your response.

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Consider the analogy Sandel draws between parents’ efforts to ensure the best for their children—

that is, sending them to expensive schools, hiring private tutors, providing music and other artistic enrichment— and the possibility of their choosing to genetically enhance their children’s intellectual ability, athletic ability, and physical appearance. Where would you draw the line between what is acceptable and what is not? And why? Bonnie Steinbock, PhD, is a professor of philosophy at the University at Albany, State University of New York, with a specialty in bioethics. In an October 2008 article in the Lancet, a well-

regarded British medical journal, she argues that “it’s far from obvious that such interventions [as genetic engineering] would be wrong” and concludes as follows: Genetic enhancement of embryos is, for the present, science fiction. Its opponents think that we need to ban it now, before it ever becomes a reality. What they have not provided are clear reasons to agree. Their real opposition is not to a particular means of shaping children, but rather to a certain style of parenting. Rather than fetishising the technology, the discussion should focus on which parental attitudes and modes of parenting help children to flourish. It may be that giving children “genetic edges” of certain kinds would not constrain their lives and choices, but actually make them better. That possibility should not be dismissed out of hand.

Are you more in agreement with Sandel in “The Case against Perfection” or with Steinbock? Explain with specific references to Sandel’s essay.

Much of Sandel’s argument in this section pivots on the distinction between accepting and transforming love. Psychologists tell us that accepting love is essential for healthy emotional development of a child. To what extent do you think that permitting all types of genetic enhancement might eliminate the very concept of accepting love?

What would you do? Imagine that ten years from now you want to have a child and technology that would enable you to deliberately choose specific mental or physical characteristics of the child is available. Would you use the technology or take your chances on a throw of the genetic dice?

Topics for Composing

Argument

Ultimately, how does Sandel challenge the case for perfection? Do you believe that striving for perfection is a worthy goal? A dangerous pursuit? A futile effort? Where do you draw the ethical line between what is acceptable and what is not? Is there truth in the saying that “perfect is the enemy of the good”? Explain your response with examples from your own experience and reading as well as reference to Sandel.Page 426Research/Exposition

After researching the topic of genetically engineering children, explain what you believe are the most compelling ethical concerns. Consider “The Case against Perfection” in your response. You might also read other works by Sandel, listen to one or more of his lectures, or explore additional works on your own. You might also consult two U.S. government websites: the Human Genome Project and the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues.Research/Exposition

Read “The Birthmark” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, a short story about a scientist’s obsession to remove his wife’s birthmark. What does this story have to say about the pursuit of perfection?Research/Argument

In a review of Sandel’s book that is an expansion of this essay, The Case against Perfection, critic William Saletan questions whether the ideas are outdated. He points out that in an earlier era, having a coach was believed to violate the spirit of sportsmanlike competition. He then asks: “Once gene therapy becomes routine, the case against genetic engineering will sound as quaint as the case against [. . .] coaches. If the genetic lottery were better than the self-made man, we might prefer the old truth to the new one. But Sandel’s egalitarian fatalism already feels a bit 20th- century.” Explain why you agree or disagree with Saletan’s assessment. Speech/Argument

Sandel’s argument pivots on his definition of what it means to be a parent in the early twenty-first century. Write a speech that you would deliver to an audience of parents from your community explaining why you agree or disagree with Sandel’s viewpoint. Exposition

The 1997 sci-fi film Gattaca explores the consequences of genetic engineering. After viewing the film, explain what position the filmmakers take on the subject. Research/Exposition

Broadly speaking, “The Case against Perfection” focuses on the complex ethical issues created by a new technology. Choose another example of technology and discuss the moral or ethical issues that it raises. You might choose a current technology, a technological development from the past, or a new emerging technology.Multimodal/Argument

Choose one point or statement that Sandel makes and challenge or support it with your own observations, experience, or knowledge. Make your argument using only images (still, moving, or a combination) and sound but no words (neither voice-over narration nor written text).