8.11

2000 lbs.

Brian Turner

Brian Turner (b. 1967) is the author of two collections of poetry, Phantom Noise and Here, Bullet, as well as a memoir, My Life as a Foreign Country. Turner served for seven years in the U.S. military, including one year during the Iraq War, which is the setting for this poem about the effects of a car bomb detonation in a crowded market.

Ashur Square, Mosul

It begins simply with a fist, white-

and tight, glossy with sweat. With two eyes

in a rearview mirror watching for a convoy.

The radio a soundtrack that adrenaline has

5 pushed into silence, replacing it with a heartbeat,

his thumb trembling over the button.

A flight of gold, that’s what Sefwan thinks

as he lights a Miami, draws in the smoke

and waits in his taxi at the traffic circle.

10 He thinks of summer 1974, lifting

pitchforks of grain high in the air,

the slow drift of it like the fall of Shatha’s hair,

and although it was decades ago, he still loves her,

remembers her standing at the canebrake

15 where the buffalo cooled shoulder-

pleased with the orange cups of flowers he brought her,

and he regrets how so much can go wrong in a life,

how easily the years slip by, light as grain, bright

as the street’s concussion of metal, shrapnel

20 traveling at the speed of sound to open him up

in blood and shock, a man whose last thoughts

are of love and wreckage, with no one there

to whisper him gone.

Sgt. Ledouix of the National Guard

25 speaks but cannot hear the words coming out,

and it’s just as well his eardrums ruptured

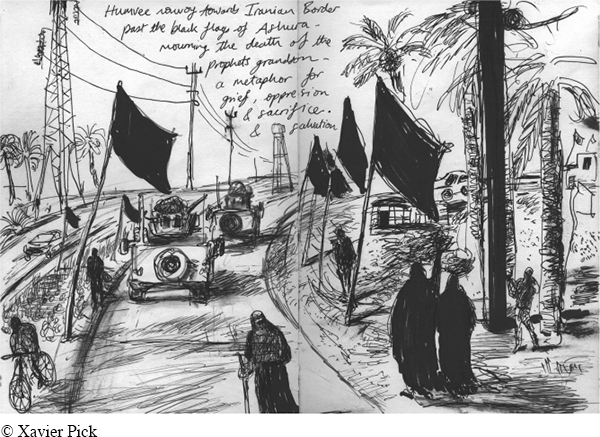

British artist Xavier Pick spent six weeks with British, American, and Iraqi armed forces in the Basra region in 2008. His caption reads: “Humvee convoy towards Iranian Border past the black flags of Ashura—

because it lends the world a certain calm,

though the traffic circle is filled with people

running in panic, their legs a blur

30 like horses in a carousel, turning

and turning the way the tires spin

on the Humvee flipped to its side,

the gunner’s hatch he was thrown from

a mystery to him now, a dark hole

35 in metal the color of sand, and if he could,

he would crawl back inside of it,

and though his fingertips scratch at the asphalt

he hasn’t the strength to move:

shrapnel has torn into his ribcage

40 and he will bleed to death in ten minutes,

but he finds himself surrounded by a strange

beauty, the shine of light on the broken,

a woman’s hand touching his face, tenderly

the way his wife might, amazed to find

45 a wedding ring on his crushed hand,

the bright gold sinking in flesh

going to bone.

Rasheed passes the bridal shop

on a bicycle, with Sefa beside him,

50 and just before the air ruckles and breaks

he glimpses the sidewalk reflections

in the storefront glass, men and women

walking and talking, or not, an instant

of clarity, just before each of them shatters

55 under the detonation’s wave,

as if even the idea of them were being

destroyed, stripped of form,

the blast tearing into the manikins

who stood as though husband and wife

60 a moment before, who cannot touch

one another, who cannot kiss,

who now lie together in glass and debris,

holding one another in their half-

calling this love, if this is all there will ever be.

65 The civil affairs officer, Lt. Jackson, stares

at his missing hands, which make

no sense to him, no sense at all, to wave

these absurd stumps held in the air

where just a moment before he’d blown bubbles

70 out the Humvee window, his left hand holding the bottle,

his right hand dipping the plastic ring in soap,

filling the air behind them with floating spheres

like the oxygen trails of deep ocean divers,

something for the children, something beautiful,

75 translucent globes with their iridescent skins

drifting on vehicle exhaust and the breeze

that might lift one day over the Zagros mountains,

that kind of hope, small globes which may have

astonished someone on the sidewalk

80 seven minutes before Lt. Jackson blacks out

from blood loss and shock, with no one there to bandage

the wounds that would carry him home.

Nearby, an old woman cradles her grandson,

whispering, rocking him on her knees

85 as though singing him to sleep, her hands

wet with their blood, her black dress

soaked in it as her legs give out

and she buckles with him to the ground.

If you’d asked her forty years earlier

90 if she could see herself an old woman

begging by the roadside for money, here,

with a bomb exploding at the market

among all these people, she’d have said

To have your heart broken one last time

95 before dying, to kiss a child given sight

of a life he could never live? It’s impossible,

this isn’t the way we die.

And the man who triggered the button,

who may have invoked the Prophet’s name,

100 or not — he is obliterated at the epicenter,

he is everywhere, he is of all things,

his touch is the air taken in, the blast

and wave, the electricity of shock,

his is the sound the heart makes quick

105 in the panic’s rush, the surge of blood

searching for light and color, that sound

the martyr cries filled with the word

his soul is made of, Inshallah.

Still hanging in the air over Ashur Square,

110 the telephone line snapped in two, crackling

a strange incantation the dead hear

as they wander confused amongst one another,

learning each other’s names, trying to comfort

the living in their grief, to console

115 those who cannot accept such random pain,

speaking habib softly, one to another there

in the rubble and debris, habib

over and over, that it might not be forgotten.

Understanding and Interpreting

How would you characterize the speaker of this poem? What does the speaker know and not know, or report and not report? How does Turner’s choice of speaker relate to the theme of the poem?

In the second stanza, Sefwan thinks the detonation looks like a “flight of gold” (l. 7), which is an image of beauty, even as it destroys. Identify other places where Turner intentionally juxtaposes images of beauty with destruction. What is the purpose of these contrasts?

Page 604Does everyone in the poem die the same way, or are there differences in their deaths? Explain how these similarities or differences support a point Turner is making about life and death.

Turner takes the reader inside the thoughts of each of the characters in the poem, with the exception of the man in the first and seventh stanzas. What is the effect of this narrative choice?

Many of the characters in the poem have flashbacks before their deaths. What seems to be in common among the topics of these flashbacks, and why would Turner choose these topics?

There is a shift in the final stanza; we do not get the perspective of one single person. In terms of plot, what happens in this final stanza, and how does the shift of narrative focus illustrate a theme of the poem?

References to love appear throughout the poem. What is Turner saying about love, and what does he accomplish by using this tragic incident to make his point?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

The first line of the poem begins with “it,” and the last line includes the word “it.” What does “it” refer to, and how are those two uses of the pronoun related?

Look at stanzas 2–

6, select two of them, and look closely at how they are structured. How does each stanza begin (for example, before, after, or during the explosion), what information does the reader receive in the middle of the stanza, and how does the stanza end? What is Turner suggesting through the structure of each stanza? The poem has eight stanzas, in which we get the alternating perspectives of six different people. How does Turner’s decision to structure his poem in this manner reflect the meaning of the poem?

People who have survived terrible accidents sometimes say that time seemed to stand still as the event was occurring. What language and structural choices does Turner make in this poem to create a similar feeling?

How does the inclusion of words in Arabic—

Inshallah and habib—illustrate Turner’s overall tone toward the events presented in the poem? In stanza seven, Turner uses the word “martyr” in reference to the man who detonated the bomb. What does the use of this word, instead of other possible words, suggest about the meaning of the poem?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Discuss whether Turner is too sympathetic to the man who sets off the bomb, using evidence from the poem to support your position.

Turner served for seven years in the U.S. Army, spending time in Iraq and other war zones. To what extent does his background give him a level of credibility or authenticity that affects how you read the poem?

The expression Turner chooses to end the stanza about the man who sets off the bomb is “Inshallah,” which is often translated from Arabic as “God willing.” Nevertheless, the term’s full meaning and its usage are more complex than this translation may suggest. Conduct research into the usage of the expression inshallah, and explain the similarities and differences in how the phrase is used in two or more cultures.

Write an additional stanza of Turner’s poem from the perspective of a bystander who witnesses the death of one of the characters depicted in one of the other stanzas. Try to use the same structure and narrative point of view that Turner employs.