8.15

from Letters from an American Farmer

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur

Michel-

What Is an American?

I wish I could be acquainted with the feelings and thoughts which must agitate the heart and present themselves to the mind of an enlightened Englishman, when he first lands on this continent. He must greatly rejoice that he lived at a time to see this fair country discovered and settled; he must necessarily feel a share of national pride, when he views the chain of settlements which embellishes these extended shores. When he says to himself, this is the work of my countrymen, who, when convulsed by factions, afflicted by a variety of miseries and wants, restless and impatient, took refuge here. They brought along with them their national genius, to which they principally owe what liberty they enjoy, and what substance they possess. Here he sees the industry of his native country displayed in a new manner, and traces in their works the embrios of all the arts, sciences, and ingenuity which flourish in Europe. Here he beholds fair cities, substantial villages, extensive fields, an immense country filled with decent houses, good roads, orchards, meadows, and bridges, where an hundred years ago all was wild, woody and uncultivated! What a train of pleasing ideas this fair spectacle must suggest; it is a prospect which must inspire a good citizen with the most heartfelt pleasure. The difficulty consists in the manner of viewing so extensive a scene. He is arrived on a new continent; a modern society offers itself to his contemplation, different from what he had hitherto seen. It is not composed, as in Europe, of great lords who possess every thing and of a herd of people who have nothing. Here are no aristocratical families, no courts, no kings, no bishops, no ecclesiastical dominion, no invisible power giving to a few a very visible one; no great manufacturers employing thousands, no great refinements of luxury. The rich and the poor are not so far removed from each other as they are in Europe. Some few towns excepted, we are all tillers of the earth, from Nova Scotia to West Florida. We are a people of cultivators, scattered over an immense territory communicating with each other by means of good roads and navigable rivers, united by the silken bands of mild government, all respecting the laws, without dreading their power, because they are equitable. We are all animated with the spirit of an industry which is unfettered and unrestrained, because each person works for himself. [. . .]

What attachment can a poor European emigrant have for a country where he had nothing? The knowledge of the language, the love of a few kindred as poor as himself, were the only cords that tied him: his country is now that which gives him land, bread, protection, and consequence: Ubi panis ibi patria,1 is the motto of all emigrants. What then is the American, this new man? He is either an European, or the descendant of an European, hence that strange mixture of blood, which you will find in no other country. I could point out to you a family whose grandfather was an Englishman, whose wife was Dutch, whose son married a French woman, and whose present four sons have now four wives of different nations. He is an American, who leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds.

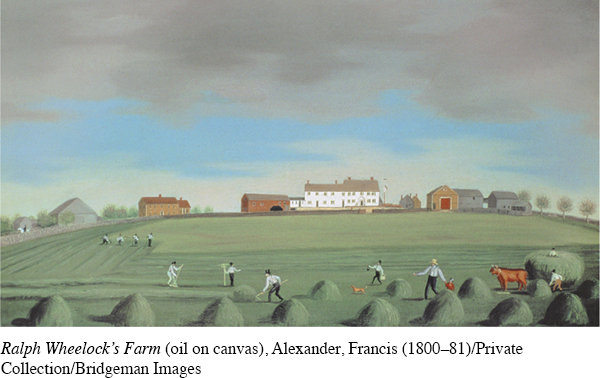

While this painting, Ralph Wheelock’s Farm by Francis Alexander, was created forty years after Crèvecoeur published his Letters from an American Farmer, it depicts an America that is similar to the one Crèvecoeur presents.

He becomes an American by being received in the broad lap of our great Alma Mater. Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world. Americans are the western pilgrims, who are carrying along with them that great mass of arts, sciences, vigour, and industry which began long since in the east; they will finish the great circle. The Americans were once scattered all over Europe; here they are incorporated into one of the finest systems of population which has ever appeared, and which will hereafter become distinct by the power of the different climates they inhabit. The American ought therefore to love this country much better than that wherein either he or his forefathers were born. Here the rewards of his industry follow with equal steps the progress of his labour; his labour is founded on the basis of nature, self-

Understanding and Interpreting

This excerpt begins by asking the reader to imagine seeing America through the eyes of “an enlightened Englishman.” Explain how Crèvecoeur says this Englishman would feel.

The middle section of the excerpt draws contrasts between America and Europe. Make a T-

chart or a Venn diagram that illustrates the similarities and differences that Crèvecoeur identifies. How do the contrasts support the central idea of the text? According to Crèvecoeur, why should Americans love their new country more than their former nation?

Put into your own words what Crèvecoeur means when he writes that an American is a “new man.”

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Who is Crèvecoeur’s audience for this piece? How do you know? What does Crèvecoeur do to appeal to and avoid insulting this audience?

If part of Crèvecoeur’s purpose in writing this piece is to persuade people to immigrate to America, how successful is his argument?

What evidence does Crèvecoeur provide to support his claim that “[h]ere individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men” (par. 3)?

Examine the word choices that Crèvecoeur uses to distinguish between America and Europe. How do these choices help or hinder Crèvecoeur’s argument?

Trace Crèvecoeur’s use of pronouns. When and for what effect does he use “he,” “we,” “them,” and “I”?

Crèvecoeur published this piece in 1782, soon after the conclusion of the American Revolution. How does the occasion of his writing affect his purpose and his tone?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

To what extent is America, as Crèvecoeur suggests, a pot in which everyone from other countries is melted into a new race? Is it more like a “salad bowl,” as described in the opening of this Conversation, and if so, why? Alternatively, what might be a more appropriate metaphor for how immigrants become Americans?

At the time of Crèvecoeur’s writing, farming was the most common American profession, but now it is retail sales. Write a “Letter from an American Salesperson” in an attempt to persuade people to immigrate to—

or dissuade them from moving to— the United States today. Is today’s America still as different from Europe as it was in Crèvecoeur’s time? What has changed and what has remained the same? Are there other countries or parts of the world that are as different from America today as Crèvecoeur says Europe was at the time? Explain.