8.17

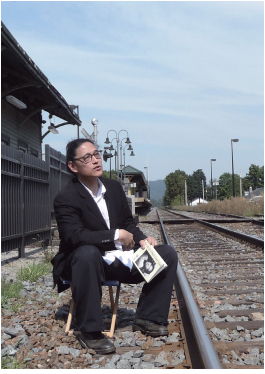

For a New Citizen of These United States

Li-

Poet Li-

Forgive me for thinking I saw

the irregular postage stamp of death;

a black moth the size of my left

thumbnail is all I’ve trapped in the damask.

5 There is no need for alarm. And

there is no need for sadness, if

the rain at the window now reminds you

of nothing; not even of that

parlor, long like a nave, where cloud-

10 wing-

continually confused the light. In flight,

leaf-

flags deepened those windows to submarine.

But you don’t remember, I know,

15 so I won’t mention that house where Chung hid,

Lin wizened, you languished, and Ming-

Ming hush-

don’t recall the missionary

bells chiming the hour, or those words whose sounds

20 alone exhaust the heart — garden,

heaven, amen — I’ll mention none of it.

After all, it was just our life,

merely years in a book of years. It was

1960, and we stood with

25 the other families on a crowded

railroad platform. The trains came, then

the rains, and then we got separated.

And in the interval between

familiar faces, events occurred, which

30 one of us faithfully pencilled

in a day-

But birds, as you say, fly forward.

So I won’t show you letters and the shawl

I’ve so meaninglessly preserved.

35 And I won’t hum along, if you don’t, when

our mothers sing Nights in Shanghai.

I won’t, each Spring, each time I smell lilac,

recall my mother, patiently

stitching money inside my coat lining,

40 if you don’t remember your mother

preparing for your own escape.

After all, it was only our

life, our life and its forgetting.

Understanding and Interpreting

Although the speaker of the poem says that he or she will “mention none of it” (l. 21), quite a bit of information of the past comes out about the time before coming to America. What are some of the most significant past events identified in the poem?

How would you characterize the relationship between the speaker and the “you” that he or she is addressing? How are their feelings about the past different? What can you infer about the cause of their conflict?

The speaker identifies letters and other objects that have been “so meaninglessly preserved” (l. 34). What factors might cause the speaker to claim that these are “meaningless”? Why does the speaker refer to them in this way?

There are many references to intentional forgetting or not remembering. What is Lee suggesting about the role of memory? What evidence from the poem supports your claim?

The title implies that this poem will include advice for recent immigrants to America. What suggestions do you think the speaker might offer about the difficulties associated with immigration?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

The past in this poem is shrouded in mystery and vagueness. Locate a section where the speaker describes the past and explain how the poet’s word choice creates a lack of clarity.

It is over halfway through the poem before the reader receives the most concrete image of the past: “It was / 1960, and we stood with / the other families on a crowded / railroad platform” (ll. 23–

26). How do these lines signal a shift in the speaker’s representation of the past? Unlike other poems you may have read, “For a New Citizen of These United States” employs very little rhyme or rhythmic pattern. How does Lee’s choice of “free verse” reflect the speaker’s attitude toward the past?

In the stanza after the trains are separated (ll. 28–

31), the speaker dismisses the details afterward by saying simply “events occurred.” How does this choice reflect the conflict between the “you” of the poem and the speaker? Twice, the speaker begins a stanza with a variation of “After all, it was just our life.” How does this reveal the speaker’s attitude toward the process of immigration?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Despite the speaker’s professed desire to leave the past behind, he or she has saved artifacts such as the letters and the shawl. What are some items from your own past that you have not let go of that hold some meaning for you, such as trophies, stuffed animals, or pieces of jewelry? Why have you kept them? What meaning do they hold for you?

It is clear the speaker’s arrival in the United States was an escape from something that was happening in the home country rather than a simple immigration. Research America’s current policy on political refugees seeking asylum from oppressive governments, focusing on who is allowed in the country for emergency reasons and who is not. Write an explanation of the policy and argue for any changes that you would recommend.

In another poem, called “A Hymn to Childhood,” Li-

Young Lee writes: Which childhood?

The one from which you’ll never escape? You,

so slow to know

what you know and don’t know.

To what extent would the speaker of “For a New Citizen of These United States” agree or disagree with this perspective of childhood?