8.2

Part 1 When the Emperor Was Divine

In the beginning the boy thought he saw his father everywhere. Outside the latrines. Underneath the showers. Leaning against barrack doorways. Playing go with the other men in their floppy straw hats on the narrow wooden benches after lunch. Above them blue skies. The hot midday sun. No trees. No shade. Birds.

It was 1942. Utah. Late summer. A city of tar-

For it was true, they all looked alike. Black hair. Slanted eyes. High cheekbones. Thick glasses. Thin lips. Bad teeth. Unknowable. Inscrutable.

That was him, over there.

5 The little yellow man.

. . .

Three times a day the clanging of bells. Endless lines. The smell of liver drifting out across the black barrack roofs. The smell of catfish. From time to time, the smell of horse meat. On meatless days, the smell of beans. Inside the mess hall, the clatter of forks and spoons and knives. No chopsticks. An endless sea of bobbing black heads. Hundreds of mouths chewing. Slurping. Sucking. Swallowing. And over there, in the corner, beneath the flag, a familiar face.

The boy called out, “Papa,” and three men with thick metal-

What is it?

But the boy could not say what it was.

10 He lowered his head and skewered a small Vienna sausage. His mother reminded him, once again, not to shout out in public. And never to speak with his mouth full. Harry Yamaguchi tapped a spoon on a glass and announced that the head count would be taken on Monday evening. The boy’s sister nudged him under the table, hard, with the scuffed toe of her Mary Jane. “Papa’s gone,” she said. [. . .]

On their first day in the desert his mother had said, “Be careful,”

“Do not touch the barbed-

“Do not stare at the sun.

“And remember, never say the Emperor’s name out loud.”

15 The boy wore a blue baseball cap and he did not stare at the sun. He often wandered the firebreak with his head down and his hands in his pockets, looking for seashells and old Indian arrowheads in the sand. Some days he saw rattlesnakes sleeping beneath the sagebrush. Some days he saw scorpions. Once he came across a horse skull bleached white by the sun. Another time, an old man in a red silk kimono with a tin pail in his hand who said he was going down to the river.

Whenever the boy walked past the shadow of a guard tower he pulled his cap down low over his head and tried not to say the word.

But sometimes it slipped out anyway.

Hirohito, Hirohito, Hirohito.

He said it quietly. Quickly. He whispered it. [. . .]

20 The man scrubbing pots and pans in the mess hall had once been the sales manager of an import-

One evening as the boy’s mother was hauling back a bucket of water from the washroom she ran into her former housekeeper, Mrs. Ueno. “When she saw me she grabbed the bucket right out of my hands and insisted upon carrying it home for me. ‘You’ll hurt your back again,’ she said. I tried to tell her that she no longer worked for me. ‘Mrs. Ueno,’ I said, ‘here we’re all equals,’ but of course she wouldn’t listen. When we got back to the barracks she set the bucket down by the front door and then she bowed and hurried off into the darkness. I didn’t even get a chance to thank her.”

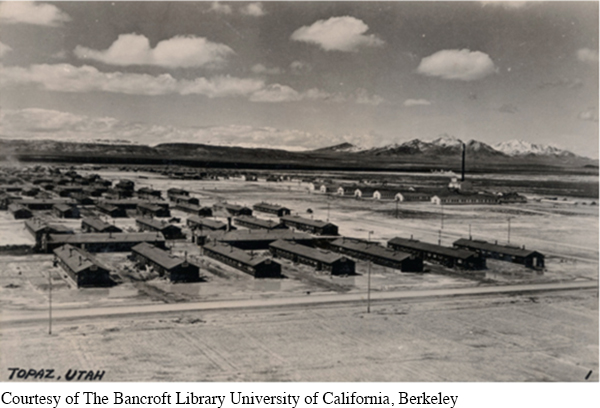

This is a picture of the Topaz camp that was used as a postcard by one of the internees. The back of the postcard says: “Dec 16, 1944. Mr. and Mrs. Uchida. Our concentration camp in Topaz, Utah. The barbed wire fence and guard towers are not visible.”

seeing connections

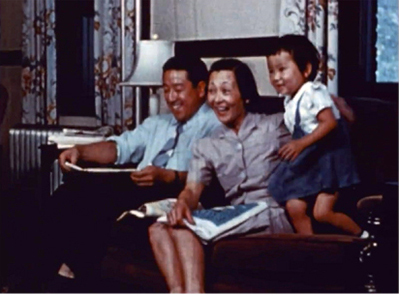

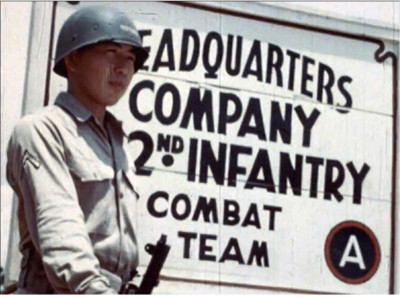

In 1944, after two years of Japanese imprisonment, the U.S. War Relocation Authority produced a propaganda film called A Challenge to Democracy in order to counter rising opposition to the internment camps. The pictures shown here are still images from the film and the accompanying passages are excerpts from the voice-

Look at each image, carefully read the script of the narration, and explain how the film uses visuals and word choice to attempt to show the internment in the best possible way. Consider as well how the images and text differ from what you have read in this excerpt from When the Emperor Was Divine.

“Evacuation: more than 100,000 men, women and children all of Japanese ancestry removed from their homes in the Pacific coast states to wartime communities established in out-

What is the effect of the words and phrases that the narrator is using to describe the Japanese?

“There can be no question of the constitutionality of any part of the action taken by the government to meet the dangers of war, so no law-

Based on the language choices, who is the target audience for this film?

“The Americanism of the great majority of America’s Japanese finds its highest expression in the thousands who are in the United States Army. Almost half of them are in a Japanese-

What is the narrator implying when he says the “American ideals that are part of their upbringing?”

“Maybe you can thank her tomorrow,” said the boy.

“I don’t even know where she lives. I don’t even know what day it is.”

“It’s Tuesday, Mama.” [. . .]

25 His sister had long skinny legs and thick black hair and wore a gold French watch that had once belonged to their father. Whenever she went out she covered her head with a wide-

“Nobody’s looking at me anyway,” he replied.

Late at night, after the lights had gone out, she told him things. Beyond the fence, she said, there was a dry riverbed and an abandoned smelter mine and at the edge of the desert there were jagged blue mountains that rose up into the sky. The mountains were farther away than they seemed. Everything was, in the desert. Everything except water. “Water,” she said, “is just a mirage.”

A mirage was not there at all.

The mountains were called Big Drum and Little Drum, Snake Ridge, the Rubies. The nearest town over was Delta.

30 In Delta, she said, you could buy oranges.

In Delta there were green leafy trees and blond boys on bikes and a hotel with a verandah where the waiters served ice-

“What else?” asked the boy.

In Delta, she said, there was shade.

She told him about the ancient salt lake that had once covered all of Utah and parts of Nevada. This was thousands of years ago, she said, during the Ice Age. There were no fences then. And no names. No Utah. No Nevada. Just lots and lots of water. “And where we are now?”

35 “Yes?”

“Six hundred feet under.” [. . .]

Every few days the letters arrived, tattered and torn, from Lordsburg, New Mexico. Sometimes entire sentences had been cut out with a razor blade by the censors and the letters did not make any sense. Sometimes they arrived in one piece, but with half of the words blacked out. Always, they were signed, “From Papa, With Love.”

Lordsburg was a nice sunny place on a broad highland plain just north of the Mexican border. That was how his father had described it in his letters. There are no trees here but the sunsets are beautiful and on clear days you can see the hills rising up in the distance. The food is fresh and substantial and my appetite is good. Although it is still very warm I have begun taking a cold shower every morning to better prepare myself for the winter. Please write and tell me what you are interested in these days. Do you still like baseball? How is your sister? Do you have a best friend?

The boy still liked baseball and he was very interested in outlaws. He had seen a movie about the Dalton Gang — When the Daltons Rode — in Recreation Hall 22. His sister had won second prize in a jitterbug contest at the mess hall. She wore her hair in a ponytail. She was fine. The boy did not have a best friend but he had a pet tortoise that he kept in a wooden box filled with sand right next to the barrack window. He had not given the tortoise a name but he had scratched his family’s identification number into its shell with the tip of his mother’s nail file. At night he covered the box with a lid and on top of the lid he placed a flat white stone so the tortoise could not escape. Sometimes, in his dreams, he could hear its claws scrabbling against the side of the box.

40 He did not mention the scrabbling claws to his father. He did not mention his dreams.

What he said was, Dear Papa: It’s pretty sunny here in Utah too. The food is not so bad and we get milk every day. In the mess hall we are collecting nails for Uncle Sam. Yesterday my kite got stuck on the fence.

The rules about the fence were simple: You could not go over it, you could not go under it, you could not go around it, you could not go through it.

And if your kite got stuck on it?

That was an easy one. You let the kite go.

45 There were rules about language, too: Here we say Dining Hall and not Mess Hall; Safety Council, not Internal Police; Residents, not Evacuees; and last but not least, Mental Climate, not Morale.

There were rules about food: No second helpings except for milk and bread.

And books: No books in Japanese.

There were rules about religion: No Emperor-

His father was a small handsome man with delicate hands and a raised white scar on his index finger that the boy, as a young child, had loved to kiss. “Does it hurt?” he’d once asked him. “Not anymore,” his father had replied. He was extremely polite. Whenever he walked into a room he closed the door behind him softly. He was always on time. He wore beautiful suits and did not yell at waiters. He loved pistachio nuts. He believed that fruit juice was the ideal drink. He liked to doodle. He was especially fond of drawing a box and then making it into three dimensions. I guess you could say that’s my forte. Whenever the boy knocked on his door his father would look up and smile and put down whatever it was he was doing. “Don’t be shy,” he’d say. He read the Examiner every morning before work and he knew the answers to everything. How small a germ was and when did fish sleep and where did Kitty McKenzie go after they took her out of her iron lung? You don’t have to worry about Kitty McKenzie anymore. She’s in a better place now. She’s up there in heaven. I heard they threw her a big party the day she arrived. He knew when to leave the boy’s mother alone and how best to ask her for ice cream. Don’t ask her too often and when you do, don’t let her know how much you really want it. Don’t beg. Don’t whine. He knew which restaurants would serve them lunch and which would not. He knew which barbers would cut their kind of hair. The best ones, of course. The thing that he loved most about America, he once confided to the boy, was the glazed jelly donut. Can’t be beat. [. . .], pp. 63–

50 One evening, while they were walking, the boy reached over and grabbed the girl’s arm. “What is it?” she asked him.

He tapped his wrist. “Time,” he said. “What time?”

She stopped and looked at her watch as though she had never seen it before. “It’s six o’clock,” she said.

Her watch had said six o’clock for weeks. She had stopped winding it the day they had stepped off the train.

“What do you think they’re doing back home?”

55 She looked at her watch one more time and then she stared up at the sky, as though she were thinking. “Right about now,” she said, “I bet they’re having a good time.” Then she started walking again.

And in his mind he could see it: the tree-

When he thought of the world outside it was always six o’clock. A Wednesday or a Thursday. Dinnertime across America.

In early autumn the farm recruiters arrived to sign up new workers, and the War Relocation Authority allowed many of the young men and women to go out and help harvest the crops. Some of them went north to Idaho to top sugar beets. Some went to Wyoming to pick potatoes. Some went to Tent City in Provo to pick peaches and pears and at the end of the season they came back wearing brand-

How does this picture demonstrate the sentence from the novel, “Life was easier, they said, on this side of the fence” (par. 58)?

The shoes were black Oxfords. Men’s, size eight and a half, extra narrow. He took them out of his suitcase and slipped them over his hands and pressed his fingers into the smooth oval depressions left behind by his father’s toes and then he closed his eyes and sniffed the tips of his fingers.

60 Tonight they smelled like nothing.

The week before they had still smelled of his father but tonight the smell of his father was gone.

He wiped off the leather with his sleeve and put the shoes back into the suitcase. Outside it was dark and in the barrack windows there were lights on and figures moving behind curtains. He wondered what his father was doing right then. Getting ready for bed, maybe. Washing his face. Or brushing his teeth. Did they even have toothpaste in Lordsburg? He didn’t know. He’d have to write him and ask. He lay down on his cot and pulled up the blankets. He could hear his mother snoring softly in the darkness, and a lone coyote in the hills to the south, howling up at the moon. He wondered if you could see the same moon in Lordsburg, or London, or even in China, where all the men wore little black slippers. And he decided that you could, depending on the clouds.

“Same moon,” he whispered to himself, “same moon.” [. . .]

Every week they heard new rumors.

65 The men and women would be put into separate camps. They would be sterilized. They would be stripped of their citizenship. They would be taken out onto the high seas and then shot. They would be sent to a desert island and left there to die. They would all be deported to Japan. They would never be allowed to leave America. They would be held hostage until every last American POW got home safely. They would be turned over to the Chinese for safekeeping right after the war.

You’ve been brought here for your own protection, they were told.

It was all in the interest of national security.

It was a matter of military necessity.

It was an opportunity for them to prove their loyalty.

70 The school was opened in mid-

Every morning, at Mountain View Elementary, he placed his hand over his heart and recited the pledge of allegiance. He sang “Oh, beautiful for spacious skies” and “My country, ’tis of thee” and he shouted out “Here!” at the sound of his name. His teacher was Mrs. Delaney. She had short brown hair and smooth creamy skin and a husband named Hank who was a sergeant in the Marines. Every week he sent her a letter from the front lines in the Pacific. Once, he even sent her a grass skirt. “Now when am I ever going to wear a grass skirt?” she asked the class.

“How about tomorrow?”

“Or after recess.”

“Put it on right now!”

75 The first week of school they learned all about the Nina and the Pinta and the Santa Maria, and Squanto and the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock. They wrote down the names of the states in neat cursive letters across lined sheets of paper. They played hangman and twenty questions. In the afternoon, during current events, they listened to Mrs. Delaney read out loud to them from the newspaper. The First Lady is visiting the Queen in London. The Russians are still holding in Stalingrad. The Japs are massing on Guadalcanal.

“What about Burma?” the boy asked.

The situation in Burma, she told the class, was bleak.

Late at night he heard the sound of the door opening, and footsteps crossing the floor, and then his sister was suddenly there by the window, flipping her dress up high over her head.

“You asleep?”

80 “Just resting.” He could smell her hair, and the dust, and salt, and he knew she’d been out there, in the night, where it was dark.

She said, “Miss me?” She said, “Turn down the radio.” She said, “I won a nickel at bingo tonight. Tomorrow we’ll go to the canteen and buy you a Coca-

He said, “I’d like that. I’d like that a lot.”

She dropped down onto the cot next to his. “Talk to me,” she said. “Tell me what you did tonight.”

“I wrote Papa a postcard.”

85 “What else?”

“Licked a stamp.”

“Do you know what bothers me most? I can’t remember his face sometimes.”

“It was sort of round,” said the boy. Then he asked her if she wanted to listen to some music and she said yes—

In the dream there was always a beautiful wooden door. The beautiful wooden door was very small — the size of a pillow, say, or an encyclopedia. Behind the small but beautiful wooden door there was a second door, and behind the second door there was a picture of the Emperor, which no one was allowed to see.

90 For the Emperor was holy and divine. A god.

You could not look him in the eye.

In the dream the boy had already opened the first door and his hand was on the second door and any minute now, he was sure of it, he was going to see God.

Only something always went wrong. The doorknob fell off. Or the door got stuck. Or his shoelace came untied and he had to bend over and tie it. Or maybe a bell was ringing somewhere — somewhere in Nevada or Peleliu or maybe it was just some crazy gong bonging in Saipan — and the nights were growing colder, the sound of the scrabbling claws was fainter now, fainter than ever before, and it was October, he was miles from home, and his father was not there.

Understanding and Interpreting

Throughout the novel, the main characters are identified only as “boy,” “girl,” “mother,” and “father.” How do you interpret the reasons for this choice?

In paragraph 14, the boy is told to “never say the Emperor’s name out loud.” What is the boy’s view of the emperor at this point? What does the emperor represent for him?

In paragraph 21, the mother runs into her former housekeeper, Mrs. Ueno. What is that interaction intended to reveal about the situation the Japanese find themselves in?

The father and boy write back and forth to each other. Read their exchange in paragraphs 37–

41. Identify what is said and what is not said in the boy’s letter, and explain what this reveals about their relationship. Make a claim about the relationship between the boy and the girl in this first section of the chapter. Use specific evidence from the text to support your statement.

Page 546While the father is absent from the camps, he is far from absent from the boy’s thoughts. What are the key details or events that the boy remembers about his father, and what do these say about the boy, as well as about the father?

The girl’s watch has stopped at 6:00, and when the boy thinks of the world outside of the camp, it is “always six o’clock. A Wednesday or a Thursday. Dinnertime across America” (par. 57). How does this section reveal a point Otsuka is making about how the boy views the various cultures of America?

The first section of this chapter ends with one of the boy’s dreams (pars. 89–

93). What does this dream likely represent? The setting plays a vitally important role in this novel; it is almost as if it is a character in the story. Choose a passage in which Otsuka describes an aspect of the camp and explain how the setting seems to affect the boy or others in the camp.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Notice Otsuka’s use of sentence fragments, especially in the opening paragraphs of this chapter. What effect is created through the use of these sentence fragments and how does that help to establish character and tone?

While this excerpt from the novel is written in the “third person” point of view, it is clearly written from the perspective of the boy. What does Otsuka do, especially with her language choices, to make it clear to the reader that we are seeing the situation through the eyes of a young boy?

Reread paragraph 45, where we learn that there are rules about the use of language in the camp. Explain the differences between some of the pairs of words that Otsuka includes, and why the authorities might have preferred certain words.

There are several places in this section of the chapter where Otsuka includes flashbacks to the characters’ lives before the camp. Identify one flashback and explain its purpose. Why is it placed where it is within the story? What does it reveal about the boy or the family?

Reread paragraphs 64–

66, which are in the section that begins with the flashback “Every week they heard new rumors.” Why does Otsuka begin almost every sentence in paragraph 65 with the word “They”? There is very little of what we typically call “plot” in this selection; the action is mostly told in short, episodic bits. What feeling is created by this choice? How does this choice reflect a theme that Otsuka is presenting?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

The boy is told to never say the emperor’s name out loud. Conduct brief research on Emperor Hirohito, or, as he was known after his death, Emperor Shōwa. What was his background, and what were his significant actions before, during, and after World War II? Beyond the title, “When the Emperor Was Divine,” what is the connection of the emperor to the events in this section of the chapter?

The father’s letters to the boy were significantly redacted or censored. To what extent should a government be able to read and censor the communications of people it suspects of treason?

In paragraph 45, the boy learns the rules about the language of the camp, such as saying “Residents” instead of “Evacuees.” Clearly this is an example of euphemistic language, much like the military term “collateral damage,” which is used instead of “civilian deaths” to minimize the negative perceptions of unintended carnage. Identify some euphemisms that you know from real life. Where do they come from, and why are they used in the context you identified?

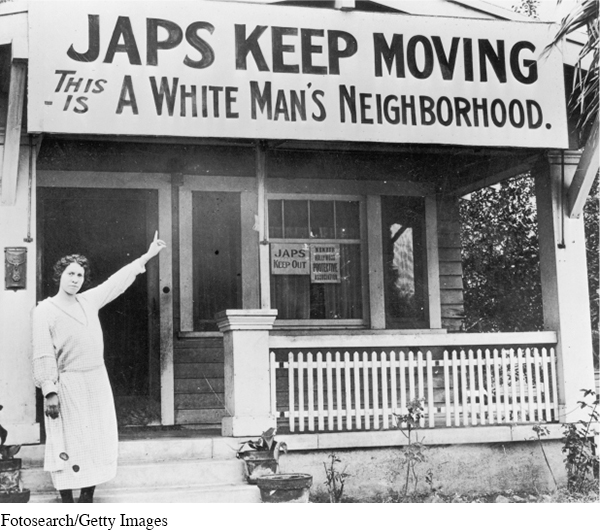

In paragraph 58, some of the Japanese who left the camp say “[l]ife was easier . . . on this side of the fence” because of the racism they experienced. Research the prejudices the Japanese (or another immigrant group) faced in U.S. society before and during World War II.