8.5

from The Storytellers of Empire

Kamila Shamsie

Writer Kamila Shamsie (b. 1973) was born and raised in Pakistan, went to college in the United States, and now lives in England. She is the author of five novels, including Burnt Shadows, as well as a nonfiction collection of essays about the perception of Islam by the West, called Offence: The Muslim Case. A frequent contributor to literary and cultural journals, Shamsie wrote this piece in 2012 for the magazine Guernica.

KEY CONTEXT In this essay, Shamsie reflects on the question she heard regularly after the terrorist attacks on the United States on 9/11/2001: why do they hate us? Getting to the answer of this question, predictably, is not easy, but one of the places she looks for answers is in the literature of war. In particular, she reflects on the book Hiroshima by John Hersey, published in 1946, which describes — in graphic detail — the effects of the atomic bomb that the United States dropped on that Japanese city.

Adisquieting thing happened to me in 2004. I had just finished my fourth novel and, unaccustomed as I was to any space of time in which I didn’t know what I would write next, I found myself searching for the single image which would lead me into a novel. Somewhat bewilderingly, instead of a single image I found myself thinking about the atom bomb falling on Nagasaki. There were a number of reasons for this — or at least, I have a number of theories about why this was so. But at the time the only thing which seemed relevant was the fact that I didn’t know anything about Nagasaki other than that a bomb fell there, yet somehow that falling bomb was getting in the way of my ability to alight on the image from which a novel would emerge.

“Of course you’ve read John Hersey’s Hiroshima,” a friend of mine said when I mentioned that atom bombs had taken up residence in my mind. I hadn’t. But I went and found it in a bookshop; it was appealingly slim enough to buy and bring home. As I read it in a single sitting I found, on page forty-

On some undressed bodies, the burns had made patterns of undershirt straps and suspenders and, on the skin of some women (since white repelled the heat from the bomb and dark clothes absorbed it and conducted it to the skin), the shapes of flowers they had had on their kimonos.

In my memory, the moment I read that line an image came of a woman facing away from me, three bird-

This is not in any way to suggest the significance of John Hersey’s work lies in its connection to my work — merely to acknowledge a debt of thanks.

Of course, the significance of Hiroshima lies in its extraordinary achievement in “bearing witness” — Hersey’s deliberately flattened tone is almost transparent, allowing us to see the images of the bombing of Hiroshima with as little mediation as possible. The line cited above illustrates this perfectly. Note the almost clinical detachment of “white repelled the heat from the bomb and dark clothes absorbed it and conducted it to the skin.” There is no need for anything more to be said, or any more emotive tone to be employed. As the actor Tara Fitzgerald recently remarked, “Melodrama is busy, tragedy isn’t.” Hersey’s pared down writing always stays on the right side of the tragedy-

5 Inevitably, it also contains within it two Americas. One is the America which develops and uses — not once, but twice — a weapon of a destructive capability which far outstrips anything that has come before, the America which decides what price some other country’s civilian population must pay for its victory. There is nothing particular to America in this — all nations in war behave in much the same way. But in the years between the bombing of Hiroshima and now, no nation has intervened militarily with as many different countries as America, and always on the other country’s soil; which is to say, no nation has treated as many other civilian populations as collateral damage as America while its own civilians stay well out of the arena of war. So that’s one of the Americas in Hiroshima —the America of brutal military power.

But there’s another America in the book, that of John Hersey. The America of looking at the destruction your nation has inflicted and telling it like it is. The America of stepping back and allowing someone else to tell their story through you because they have borne the tragedy and you have the power to bear witness to it. It is the America of the New Yorker of William Shawn, which, for the only time in its history, gave over an entire edition to a single article and kept its pages clear of its famed cartoons. It is the America which honored Hersey for his truth telling.

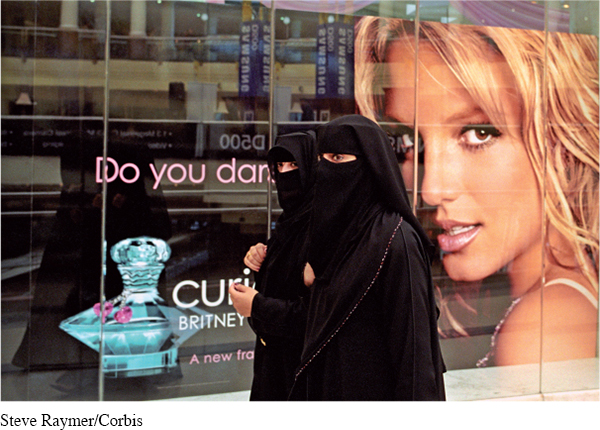

I grew up in Pakistan with two Americas. One was the America of To Kill a Mockingbird and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, of the young Michael Jackson and Laura Ingalls Wilder, of Charlie’s Angels and John McEnroe and Rob Lowe’s blue eyes. Of Martin Luther King and Snoopy. That America was exuberance and possibility.

This photograph was taken outside a shopping mall in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates.

But there was another that I lived with. The America which cozied up to Pakistan’s military dictator, Zia-

How to reconcile these two Americas? I didn’t even try. It was a country I always looked at with one eye shut. With my left eye I saw the America of John Hersey; with my right eye I saw the America of the two atom bombs. This one-

10 I don’t mean Americans looked at America uncritically. I mean they looked at it merely in domestic terms.

Then, of course, there’s [Hersey’s] vision of the American army as a sort of United Colors of Benetton in the fall collection’s Combat Pants.

I hadn’t expected anyone in America to know anything about Pakistan’s cultural life in the way that I knew about America’s cultural life. In the 1980s at traffic lights in Karachi, barefoot children, many of them refugees from Afghanistan, sold paper masks of Sylvester Stallone as Rambo. As the unfortunate among you may know, Rambo III showed that great American icon fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan and was dedicated to “the brave Mujahideen fighters of Afghanistan,” though Wikipedia informs me that after 9/11 this dedication was changed to “the people of Afghanistan.” I haven’t sat through the movie to determine the veracity of this claim. But anyway, yes, you could buy paper masks of Rambo at traffic lights. And young men in the heat of the Karachi sun wore leather jackets and pushed up their sleeves in imitation of Michael Jackson. I was never foolish enough to imagine that at traffic lights in America anyone was selling paper masks of Maula Jut, Pakistan’s mustachioed cinema icon of the same period, or dancing while moving only their upper bodies in the manner of the sultry pop singer Nazia Hasan — whose below-

This is a photograph of a police building in Tehran, Iran.

I had grown up in a country with military rule; I had grown up, that is to say, with the understanding that the government of a nation is a vastly different thing than its people. The government of America was a ruthless and morally bankrupt entity; but the people of America, well, they were different, they were better. They didn’t think it was okay for America to talk democracy from one side of its mouth while heaping praise on totalitarian nightmares from the other side. They just didn’t know it was happening, not really, not in any way that made it real to them. For a while this sufficed. I grumbled a little about American insularity. But it was an affectionate grumble. All nations have their failings. As a Pakistani, who was I to cast stones from my brittle, blood-

Then came September 11, and for a few seconds, it brought this question: why do they hate us?

15 It’s hard to remember this now, but it was a question asked loudly and genuinely, maybe not everywhere, certainly not by everyone, but by enough people. It was asked not only about the men on the planes but also about those people in the world who didn’t fall over with weeping but instead were seen to remark that now America, too, knew what it felt like to be attacked. It was asked, and very quickly it was answered: they hate our freedoms. And just like that a door was closed and a large sign pasted onto it saying, “You’re Either With Us or Against Us.” Anyone who hammered on the door with mention of the words “foreign policy” was accused of justifying the murder of more than three thousand people.

In this moment of darkness, I found myself looking to my tribe, my people. I found myself looking to writers. Where were the novels that could be proffered to people who asked, “Why do they hate us?”, which is actually the question “Who are these people and what do they have to do with us?” No such novel, as far as I knew, had come from the post–

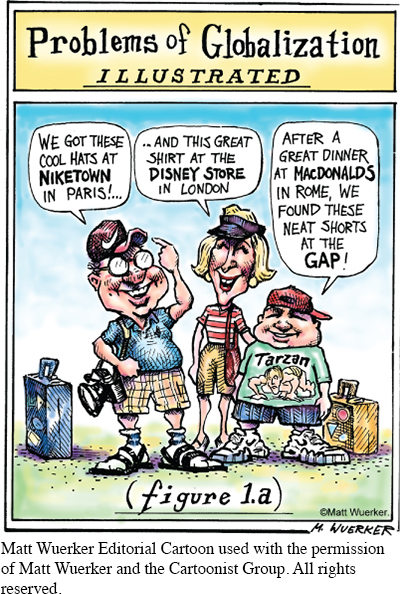

This editorial cartoon is titled Problems of Globalization. The figure number at the bottom of the image indicates that this is just one of many problems, as far as the artist is concerned.

They didn’t. They haven’t.

Let me make it clear what I’m not saying. I’m not saying September 11, the day itself in New York, is not itself a worthy subject for fiction. Only an idiot would say that. But just as the day itself is only one part of the genre of 9/11 nonfiction books, so it should be with fiction.

And here’s another thing: does writing about the day itself preclude the possibility of entwining it with other stories? A friend of mine recently remarked in exasperation that the 9/11 novel in America is always ultimately a novel of trauma experienced by individuals. It could just as well be about an earthquake which occurred without warning, led to thousands of deaths and required great bravery from the emergency services. Well, but it really happened and an earthquake didn’t, you might feel compelled to respond, and that’s true. So let’s say instead that, in American fiction, 9/11 is a traumatic event as ahistorical1 as an earthquake.

20 Your soldiers will come to our lands, but your novelists won’t. The unmanned drone hovering over Pakistan, controlled by someone in Langley, is an apt metaphor for America’s imaginative engagement with my nation.

But I fear I’m falling into the American trap of focusing too much on 9/11 as though everything started there, and in the process I’m starting to sound as though I think the losses and traumas of that day should only be a side story in some other narrative. Neither of these positions are those I wish to claim. So let’s approach it from another angle; let’s return to that mask of Rambo.

I grew up in Pakistan in the 1980s, aware that thinking about my country’s history and politics meant thinking about America’s history and politics. This is not an unusual position. Many countries of the world from Asia to South America exist, or have existed, as American client states, have seen U.S.-backed coups, faced American missiles or sanctions, seen their government’s policies on various matters dictated in Washington. America may not be an empire in the nineteenth century way which involved direct colonization. But the neo-

So in an America where fiction writers are so caught up in the Idea of America in a way that perhaps has no parallel with any other national fiction, where the term Great American Novel weighs heavily on writers, why is it that the fiction writers of my generation are so little concerned with the history of their own nation once that history exits the fifty states? It’s not because of a lack of dramatic potential in those stories of America in the World; that much is clear.

In part, I’m inclined to blame the trouble caused by that pernicious word “appropriation.” I first encountered it within a writing context within weeks, perhaps days, of arriving at Hamilton College in 1991. Right away, I knew there was something deeply damaging in the idea that writers couldn’t take on stories about the Other. As a South Asian who has encountered more than her fair share of awful stereotypes about South Asians in the British empire novels of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I’m certainly not about to disagree with the charge that writers who are implicated in certain power structures have been guilty of writing fiction which supports, justifies and props up those power structures. I understand the concerns of people who feel that for too long stories have been told about them rather than by them. But it should be clear that the response to this is for writers to write differently, to write better, to critique the power structures rather than propping them up, to move beyond stereotype — which you need to do for purely technical reasons, because the novel doesn’t much like stereotypes. They come across as bad writing.

25 The moment you say, a male American writer can’t write about a female Pakistani, you are saying, Don’t tell those stories. Worse, you’re saying, as an American male you can’t understand a Pakistani woman. She is enigmatic, inscrutable, unknowable. She’s other. Leave her and her nation to its Otherness. Write them out of your history.

Perhaps it’s telling that the first mainstream American writer to try and enter the perspective of the Other post 9/11 belonged to an older generation, less weighed down, I suspect, by ideas of appropriation: I mean John Updike, with his novel Terrorist. I confess I didn’t get past the first few pages — the figure of the young Muslim seemed such an accumulation of stereotype that it struck me as rather poor writing. And, of course, it was a story about America with the Muslim posited as the Violent and Hate-

The stories of America in the World rather than the World in America stubbornly remain the domain of nonfiction. Your soldiers will come to our lands, but your novelists won’t. The unmanned drone hovering over Pakistan, controlled by someone in Langley, is an apt metaphor for America’s imaginative engagement with my nation. [. . .]

Where is the American writer who looks on his or her country with two eyes, one shaped by the experience of living here, the other filled with the sad knowledge of what this country looks like when it’s not at home. Where is the American writer who can tell you about the places your nation invades or manipulates, brings you into those stories and lets you draw breath with its characters? [. . .]

Someone, many someones, should be writing those many different books about America.

30 Many someones are. But not in America. [. . .]

So why is it, please explain, that you’re in our stories but we’re not in yours?

Fear of appropriation? I think that argument can only take you so far. Surely fiction writers today understand the value of stories about America In the World, and can see through the appropriation argument. It is, after all, a political argument that can easily be trumped by another political argument about the importance of engagement. So why, then — why, when there are astonishing stories out in the world about America, to do with America, going straight to the heart of the question: who are these people and what do they have to do with us? — why are the fiction writers staying away from the stories? The answer, I think, comes from John Hersey. He said of novelists, “A writer is bound to have varying degrees of success, and I think that that is partly an issue of how central the burden of the story is to the author’s psyche.”

And that’s the answer. Even now, you just don’t care very much about us. One eye remains closed. The pen, writing its deliberate sentences, is icy cold.

Understanding and Interpreting

What leads Shamsie to read John Hersey’s book Hiroshima? What was she hoping to learn?

Shamsie says that Hersey is “so good at [. . .] transparency, that [. . .] it almost becomes possible to forget the nationality of the writer” (par. 4). First, how does she say Hersey achieves this transparency? Second, why does Shamsie say that this transparency is a positive achievement?

Shamsie says that Hersey represents one of two different Americas. What is the America that Hersey represents, and what is the other?

According to Shamsie, what makes 9/11 a difficult but worthy topic to write about for American authors?

According to Shamsie, what is the difference between stories of “America in the World” and “the World in America” (par. 27)? Which category fits for John Hersey? Which one for John Updike?

Another possible title of this piece could be “One Eye Shut.” How does Shamsie use this phrase in this essay, and how does it reflect the overall message she wants to communicate?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Shamsie includes several moments of personal narrative within this argumentative essay about the role of fiction in our lives. Identify one place where she inserts her own story into the argument and evaluate how effective or ineffective this section is at helping to convince her audience.

There are several places in this essay where Shamsie describes growing up in Pakistan. What information does she share about her homeland, and how does this establish her ethos as a writer?

Shamsie does not mention 9/11, the main topic of her essay, until almost halfway through. How does the information she presents first establish the context for what happens in the second half of her essay?

A key word that Shamsie uses is “appropriation.” How does she use this term to illustrate the theme of the piece? What examples does she provide? What is an opposite of the word “appropriation”?

Skim back through the piece and identify the places where Shamsie uses “you” and “our.” What patterns do you identify and how does her use of pronouns relate to her purpose for writing?

How would you characterize Shamsie’s tone toward America? What about her tone toward American writers? What evidence from the essay supports your interpretation?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Skim back through the stories that you have read so far in this textbook. Which ones are stories of “America in the World” and which ones are stories of “the World in America” as Shamsie defines these terms? Explain your reasoning.

While she asks the question rhetorically in the essay, how would you respond to Shamsie when she writes, “So why is it, please explain, that you’re in our stories but we’re not in yours” (par. 31)?

Write an argument in which you make and support a claim about how America seems to view the Middle East, and whether that view has changed during your lifetime. Use the news media as well as representations of the Middle East in popular culture such as movies, television shows, and video games.

While it may be a cliché, the phrase “history is written by the victors” is an idea with which Shamsie would likely agree. Research some “victors” who got to write history. Explain what happened, and how they put their own spin on how the events were told.