9.9

No Speak English

Sandra Cisneros

One of the first Latina writers to achieve commercial success, Sandra Cisneros (b. 1954) is a novelist, short-

Mamacita is the big mama of the man across the street, third-

The man saved his money to bring her here. He saved and saved because she was alone with the baby boy in that country. He worked two jobs. He came home late and he left early. Every day.

Then one day Mamacita and the baby boy arrived in a yellow taxi. The taxi door opened like a waiter’s arm. Out stepped a tiny pink shoe, a foot soft as a rabbit’s ear, then the thick ankle, a flutter of hips, fuchsia roses and green perfume. The man had to pull her, the taxicab driver had to push. Push, pull. Push, pull. Poof!

All at once she bloomed. Huge, enormous, beautiful to look at from the salmon-

5 Up, up, up the stairs she went with the baby boy in a blue blanket, the man carrying her suitcases, her lavender hatboxes, a dozen boxes of satin high heels. Then we didn’t see her.

Somebody said because she’s too fat, somebody because of the three flights of stairs, but I believe she doesn’t come out because she is afraid to speak English, and maybe this is so since she only knows eight words. She knows to say: He is not here for when the landlord comes, No speak English if anybody else comes, and Holy smokes. I don’t know where she learned this, but I heard her say it one time and it surprised me.

My father says when he came to this country he ate hamandeggs for three months. Breakfast, lunch and dinner. Hamandeggs. That was the only word he knew. He doesn’t eat hamandeggs anymore.

Whatever her reasons, whether she is fat, or can’t climb the stairs, or is afraid of English, she won’t come down. She sits all day by the window and plays the Spanish radio show and sings all the homesick songs about her country in a voice that sounds like a seagull.

Home. Home. Home is a house in a photograph, a pink house, pink as hollyhocks with lots of startled light. The man paints the walls of the apartment pink, but it’s not the same, you know. She still sighs for her pink house, and then I think she cries. I would.

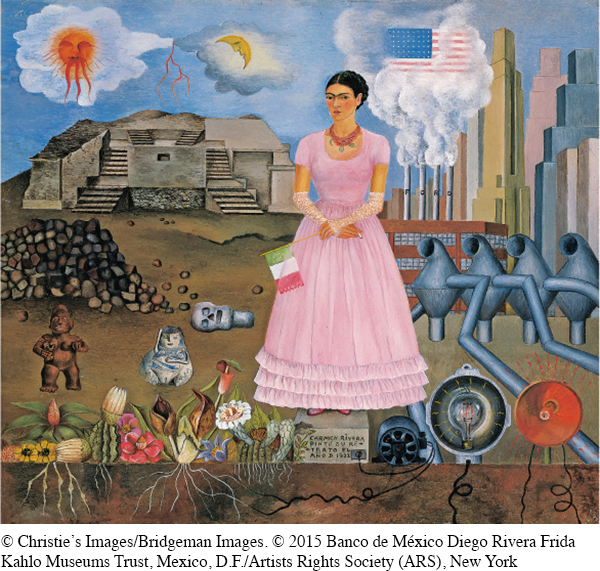

Frida Kahlo, Self-

10 Sometimes the man gets disgusted. He starts screaming and you can hear it all the way down the street.

Ay, she says, she is sad.

Oh, he says. Not again.

¿Cuándo, cuándo, cuándo?2 she asks.

¡Ay, caray! We are home. This is home. Here I am and here I stay. Speak English. Speak English. Christ!

15 ¡Ay! Mamacita, who does not belong, every once in a while lets out a cry, hysterical, high, as if he had torn the only skinny thread that kept her alive, the only road out to that country.

And then to break her heart forever, the baby boy, who has begun to talk, starts to sing the Pepsi commercial he heard on T.V.

No speak English, she says to the child who is singing in the language that sounds like tin. No speak English, no speak English, and bubbles into tears. No, no, no, as if she can’t believe her ears.

Understanding and Interpreting

What is the “joke” in the opening paragraph of the story, that is, “Mamacita” versus “Mamasota”? Is it funny or, as the narrator says, “mean,” or a little of both?

How is the man, the father, portrayed in this story? To what extent is he a sympathetic character?

What is the meaning of “home” in “No Speak English”? How important is language in defining what “home” means?

What factors or forces isolate the woman in this story? Identify at least four. Do you think one is most influential, or do several factors work cumulatively? Explain.

What different meanings do you find in the title of the story, “No Speak English”? Why do you think Cisneros suggests such ambiguity?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Who is the narrator of the story? What information do you have about her age, ethnicity, personality, and so on? How does this information contribute to her reliability as the narrator?

Cisneros describes the central character with vivid details of her physical appearance, dress, walk, and so on. Which specific details suggest a cultural clash?

To what extent do you think the narrator is exaggerating in descriptions such as the following: “[H]e ate hamandeggs for three months. Breakfast, lunch and dinner” (par. 7). What other examples can you identify? What is the narrator’s purpose in making such sweeping statements?

How does Cisneros develop the idea of entrapment through imagery and specific detail in this story?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

What issues about the relationship between language and power does this story raise? Who has power in the family across the street from the narrator?

At the end, the mother “bubbles into tears” when her son sings a soda commercial in English. Is Cisneros suggesting that the boy’s learning English is dangerous, insensitive, necessary, inevitable, or disloyal? Is it a combination of these, or something else? Support your response with specifics from this text.

Jump forward fifteen years in your imagination and write a brief narrative in the voice of the “baby boy” as a teenager. Speculate about how he sees himself and his parents.

This story is one of several vignettes—

short narrative sketches— in The House on Mango Street. Read several others and discuss the challenges immigrant families face when coming to the United States. What “translations” must they make, according to Cisneros?