9.18

Brave New World of Digital Intimacy

Clive Thompson

Born in Canada in 1968, Clive Thompson is a freelance journalist who writes mainly about technology and science and whose work regularly appears in publications such as the New York Times Magazine, the Washington Post, Lingua Franca, Wired, Shift, and Entertainment Weekly. He is the author of the book Smarter Than You Think: How Technology Is Changing Our Minds for the Better, published in 2013. In this piece, originally published in the New York Times in 2008, Thompson explores how the emergence of social networking technologies has changed the way people interact and relate.

On Sept. 5, 2006, Mark Zuckerberg changed the way that Facebook worked, and in the process he inspired a revolt.

Zuckerberg, a doe-

But Zuckerberg knew Facebook had one major problem: It required a lot of active surfing on the part of its users. Sure, every day your Facebook friends would update their profiles with some new tidbits; it might even be something particularly juicy, like changing their relationship status to “single” when they got dumped. But unless you visited each friend’s page every day, it might be days or weeks before you noticed the news, or you might miss it entirely. Browsing Facebook was like constantly poking your head into someone’s room to see how she was doing. It took work and forethought. In a sense, this gave Facebook an inherent, built-

“It was very primitive,” Zuckerberg told me when I asked him about it last month. And so he decided to modernize. He developed something he called News Feed, a built-

5 When students woke up that September morning and saw News Feed, the first reaction, generally, was one of panic. Just about every little thing you changed on your page was now instantly blasted out to hundreds of friends, including potentially mortifying bits of news — Tim and Lisa broke up; Persaud is no longer friends with Matthew — and drunken photos someone snapped, then uploaded and tagged with names. Facebook had lost its vestigial bit of privacy. For students, it was now like being at a giant, open party filled with everyone you know, able to eavesdrop on what everyone else was saying, all the time.

“Everyone was freaking out,” Ben Parr, then a junior at Northwestern University, told me recently. What particularly enraged Parr was that there wasn’t any way to opt out of News Feed, to “go private” and have all your information kept quiet. He created a Facebook group demanding Zuckerberg either scrap News Feed or provide privacy options. “Facebook users really think Facebook is becoming the Big Brother of the Internet, recording every single move,” a California student told the Star-

Zuckerberg, surprised by the outcry, quickly made two decisions. The first was to add a privacy feature to News Feed, letting users decide what kind of information went out. But the second decision was to leave News Feed otherwise intact. He suspected that once people tried it and got over their shock, they’d like it.

He was right. Within days, the tide reversed. Students began e-

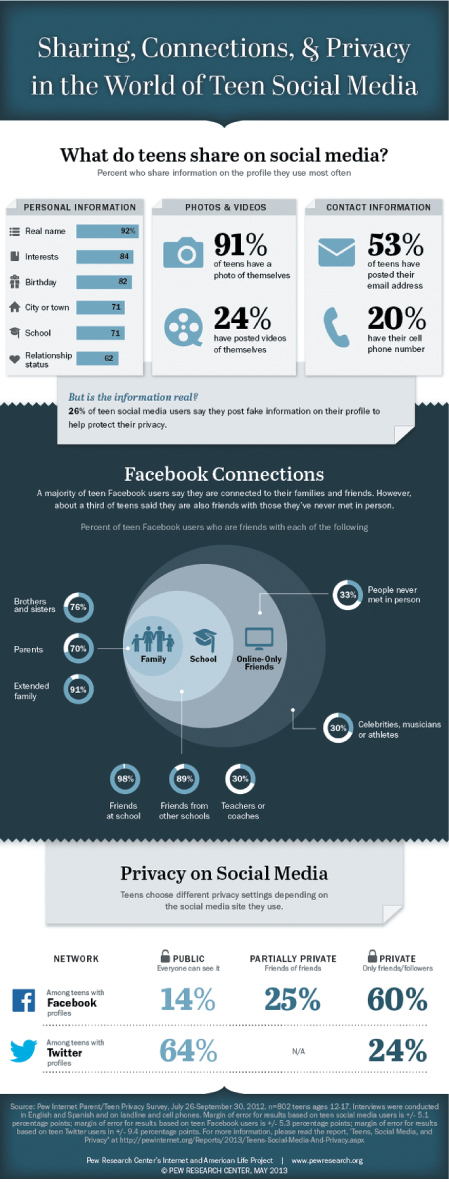

Look carefully at this graphic, which summarizes the findings of a survey of teens regarding their use of privacy settings on social networks.

When I spoke to him, Zuckerberg argued that News Feed is central to Facebook’s success. “Facebook has always tried to push the envelope,” he said. “And at times that means stretching people and getting them to be comfortable with things they aren’t yet comfortable with. A lot of this is just social norms catching up with what technology is capable of.”

10 In essence, Facebook users didn’t think they wanted constant, up-

Social scientists have a name for this sort of incessant online contact. They call it “ambient awareness.” It is, they say, very much like being physically near someone and picking up on his mood through the little things he does — body language, sighs, stray comments — out of the corner of your eye. Facebook is no longer alone in offering this sort of interaction online. In the last year, there has been a boom in tools for “microblogging”: posting frequent tiny updates on what you’re doing. The phenomenon is quite different from what we normally think of as blogging, because a blog post is usually a written piece, sometimes quite long: a statement of opinion, a story, an analysis. But these new updates are something different. They’re far shorter, far more frequent and less carefully considered. One of the most popular new tools is Twitter, a Web site and messaging service that allows its two-

For many people — particularly anyone over the age of 30 — the idea of describing your blow-

Indeed, many of the people I interviewed, who are among the most avid users of these “awareness” tools, admit that at first they couldn’t figure out why anybody would want to do this. Ben Haley, a 39-

Each day, Haley logged on to his account, and his friends’ updates would appear as a long page of one-

15 But as the days went by, something changed. Haley discovered that he was beginning to sense the rhythms of his friends’ lives in a way he never had before. When one friend got sick with a virulent fever, he could tell by her Twitter updates when she was getting worse and the instant she finally turned the corner. He could see when friends were heading into hellish days at work or when they’d scored a big success. Even the daily catalog of sandwiches became oddly mesmerizing, a sort of metronomic click that he grew accustomed to seeing pop up in the middle of each day.

This is the paradox of ambient awareness. Each little update — each individual bit of social information — is insignificant on its own, even supremely mundane. But taken together, over time, the little snippets coalesce into a surprisingly sophisticated portrait of your friends’ and family members’ lives, like thousands of dots making a pointillist painting. This was never before possible, because in the real world, no friend would bother to call you up and detail the sandwiches she was eating. The ambient information becomes like “a type of E.S.P.,” as Haley described it to me, an invisible dimension floating over everyday life.

“It’s like I can distantly read everyone’s mind,” Haley went on to say. “I love that. I feel like I’m getting to something raw about my friends. It’s like I’ve got this heads-

Facebook and Twitter may have pushed things into overdrive, but the idea of using communication tools as a form of “co-

“It’s an aggregate phenomenon,” Marc Davis, a chief scientist at Yahoo and former professor of information science at the University of California at Berkeley, told me. “No message is the single-

20 You could also regard the growing popularity of online awareness as a reaction to social isolation, the modern American disconnectedness that Robert Putnam explored in his book Bowling Alone. The mobile workforce requires people to travel more frequently for work, leaving friends and family behind, and members of the growing army of the self-

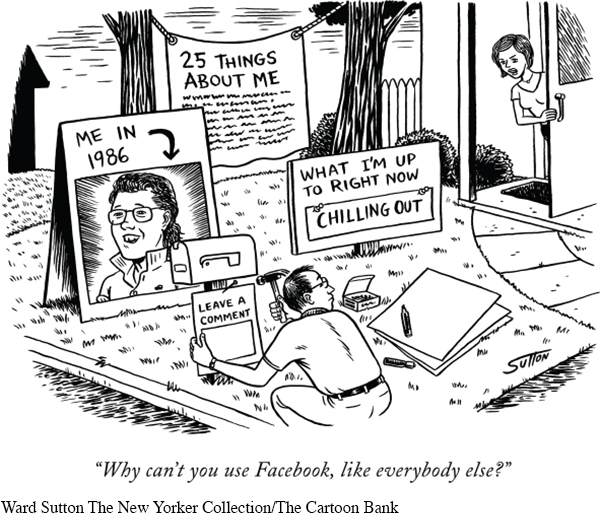

The cartoon is making a lighthearted joke about what the postings on Facebook would look like in the real world, but it can also prompt some reflection.

What is different between online and offline communication as represented in this cartoon?

When I decided to try out Twitter last year, at first I didn’t have anyone to follow. None of my friends were yet using the service. But while doing some Googling one day I stumbled upon the blog of Shannon Seery, a 32-

“I have a rule,” she told me. “I either have to know who you are, or I have to know of you.” That means she monitors the lives of friends, family, anyone she works with, and she’ll also follow interesting people she discovers via her friends’ online lives. Like many people who live online, she has wound up following a few strangers — though after a few months they no longer feel like strangers, despite the fact that she has never physically met them.

I asked Seery how she finds the time to follow so many people online. The math seemed daunting. After all, if her 1,000 online contacts each post just a couple of notes each a day, that’s several thousand little social pings to sift through daily. What would it be like to get thousands of e-

Yet she has, she said, become far more gregarious online. “What’s really funny is that before this ‘social media’ stuff, I always said that I’m not the type of person who had a ton of friends,” she told me. “It’s so hard to make plans and have an active social life, having the type of job I have where I travel all the time and have two small kids. But it’s easy to tweet all the time, to post pictures of what I’m doing, to keep social relations up.” She paused for a second, before continuing: “Things like Twitter have actually given me a much bigger social circle. I know more about more people than ever before.”

25 I realized that this is becoming true of me, too. After following Seery’s Twitter stream for a year, I’m more knowledgeable about the details of her life than the lives of my two sisters in Canada, whom I talk to only once every month or so. When I called Seery, I knew that she had been struggling with a three-

Online awareness inevitably leads to a curious question: What sort of relationships are these? What does it mean to have hundreds of “friends” on Facebook? What kind of friends are they, anyway?

In 1998, the anthropologist Robin Dunbar argued that each human has a hard-

As I interviewed some of the most aggressively social people online — people who follow hundreds or even thousands of others — it became clear that the picture was a little more complex than this question would suggest. Many maintained that their circle of true intimates, their very close friends and family, had not become bigger. Constant online contact had made those ties immeasurably richer, but it hadn’t actually increased the number of them; deep relationships are still predicated on face time, and there are only so many hours in the day for that.

But where their sociality had truly exploded was in their “weak ties” — loose acquaintances, people they knew less well. It might be someone they met at a conference, or someone from high school who recently “friended” them on Facebook, or somebody from last year’s holiday party. In their pre-

30 This rapid growth of weak ties can be a very good thing. Sociologists have long found that “weak ties” greatly expand your ability to solve problems. For example, if you’re looking for a job and ask your friends, they won’t be much help; they’re too similar to you, and thus probably won’t have any leads that you don’t already have yourself. Remote acquaintances will be much more useful, because they’re farther afield, yet still socially intimate enough to want to help you out. Many avid Twitter users — the ones who fire off witty posts hourly and wind up with thousands of intrigued followers — explicitly milk this dynamic for all it’s worth, using their large online followings as a way to quickly answer almost any question. Laura Fitton, a social-

“I outsource my entire life,” she said. “I can solve any problem on Twitter in six minutes.” (She also keeps a secondary Twitter account that is private and only for a much smaller circle of close friends and family — “My little secret,” she said. It is a strategy many people told me they used: one account for their weak ties, one for their deeper relationships.)

It is also possible, though, that this profusion of weak ties can become a problem. If you’re reading daily updates from hundreds of people about whom they’re dating and whether they’re happy, it might, some critics worry, spread your emotional energy too thin, leaving less for true intimate relationships. Psychologists have long known that people can engage in “parasocial” relationships with fictional characters, like those on TV shows or in books, or with remote celebrities we read about in magazines. Parasocial relationships can use up some of the emotional space in our Dunbar number, crowding out real-

seeing connections

The following comments are part of a focus group conducted by the Pew Internet Research Project from 2013.

Which ones are reflective of your experiences with social media and which ones are not? Which ones are most similar to or different from the conclusions drawn in “Brave New World of Digital Intimacy,” the article by Clive Thompson?

Female (age 14): “OK, so I do post a good amount of pictures, I think. Sometimes it’s a very stressful thing when it comes to your profile picture. Because one should be better than the last, but it’s so hard. So . . . I will message them a ton of pictures. And be like which one should I make my profile? And then they’ll help me out. And that kind of takes the pressure off me. And it’s like a very big thing.”

Male (age 16): “Yeah, [I’ve gotten in trouble for something I posted] with my parents. This girl posted a really, really provocative picture [on Facebook] and I called her a not very nice word [in the comments]. And I mean, I shouldn’t have called her that word, and I was being a little bit too cocky I guess, and yeah, I got in trouble with my parents.”

Male (age 17): “It sucks [when parents are friends on Facebook] . . . Because then they [my parents] start asking me questions like why are you doing this, why are you doing that. It’s like, it’s my Facebook. If I don’t get privacy at home, at least, I think, I should get privacy on a social network.”

Male (age 18): “So honestly, the only time I’ve ever deleted for a picture is because I’m applying for colleges. You know what? Colleges might actually see my pictures and I have pictures like with my fingers up, my middle fingers up. Like me and my friends have pictures, innocent fun. We’re not doing anything bad, but innocent fun. But at the same time, maybe I’m applying for college now. Possibly an admission officer’s like, you know, this kid’s accepted. Let’s see what his everyday life is like. They’re like, um—

” Male (age 18): “Yeah, I have some teachers who have connections that you might want to use in the future, so I feel like you always have an image to uphold. Whether I’m a person that likes to have fun and go crazy and go all out, but I don’t let people see that side of me because maybe it changes the judgment on me. So you post what you want people to think of you, basically.”

Female (age 16): “I deleted it [my Facebook account] when I was 15, because I think it [Facebook] was just too much for me with all the gossip and all the cliques and how it was so important to be—

have so many friends— I was just like it’s too stressful to have a Facebook, if that’s what it has to take to stay in contact with just a little people. It was just too strong, so I just deleted it. And I’ve been great ever since.”

“The information we subscribe to on a feed is not the same as in a deep social relationship,” Boyd told me. She has seen this herself; she has many virtual admirers that have, in essence, a parasocial relationship with her. “I’ve been very, very sick, lately and I write about it on Twitter and my blog, and I get all these people who are writing to me telling me ways to work around the health-

When I spoke to Caterina Fake, a founder of Flickr (a popular photo-

35 What is it like to never lose touch with anyone? One morning this summer at my local cafe, I overheard a young woman complaining to her friend about a recent Facebook drama. Her name is Andrea Ahan, a 27-

She was aghast. “I’m like, my God, these pictures are completely hideous!” Ahan complained, while her friend looked on sympathetically and sipped her coffee. “I’m wearing all these totally awful ’90s clothes. I look like crap. And I’m like, Why are you people in my life, anyway? I haven’t seen you in 10 years. I don’t know you anymore!” She began furiously detagging the pictures — removing her name, so they wouldn’t show up in a search anymore.

Worse, Ahan was also confronting a common plague of Facebook: the recent ex. She had broken up with her boyfriend not long ago, but she hadn’t “unfriended” him, because that felt too extreme. But soon he paired up with another young woman, and the new couple began having public conversations on Ahan’s ex-

“Sometimes I think this stuff is just crazy, and everybody has got to get a life and stop obsessing over everyone’s trivia and gossiping,” she said.

Yet Ahan knows that she cannot simply walk away from her online life, because the people she knows online won’t stop talking about her, or posting unflattering photos. She needs to stay on Facebook just to monitor what’s being said about her. This is a common complaint I heard, particularly from people in their 20s who were in college when Facebook appeared and have never lived as adults without online awareness. For them, participation isn’t optional. If you don’t dive in, other people will define who you are. So you constantly stream your pictures, your thoughts, your relationship status and what you’re doing — right now! — if only to ensure the virtual version of you is accurate, or at least the one you want to present to the world.

40 This is the ultimate effect of the new awareness: It brings back the dynamics of small-

“It’s just like living in a village, where it’s actually hard to lie because everybody knows the truth already,” Tufekci said. “The current generation is never unconnected. They’re never losing touch with their friends. So we’re going back to a more normal place, historically. If you look at human history, the idea that you would drift through life, going from new relation to new relation, that’s very new. It’s just the 20th century.”

Psychologists and sociologists spent years wondering how humanity would adjust to the anonymity of life in the city, the wrenching upheavals of mobile immigrant labor — a world of lonely people ripped from their social ties. We now have precisely the opposite problem. Indeed, our modern awareness tools reverse the original conceit of the Internet. When cyberspace came along in the early ’90s, it was celebrated as a place where you could reinvent your identity — become someone new.

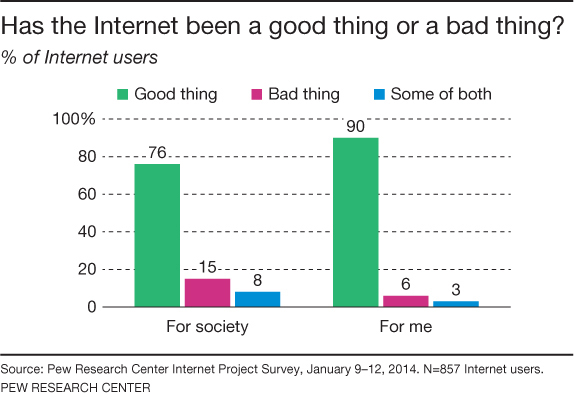

Why do you think there is a difference between how people view the Internet for themselves and for society? How would you answer the question? Why?

“If anything, it’s identity-

Or, as Leisa Reichelt, a consultant in London who writes regularly about ambient tools, put it to me: “Can you imagine a Facebook for children in kindergarten, and they never lose touch with those kids for the rest of their lives? What’s that going to do to them?” Young people today are already developing an attitude toward their privacy that is simultaneously vigilant and laissez-

45 It is easy to become unsettled by privacy-

Laura Fitton, the social-

Understanding and Interpreting

When Mark Zuckerberg added the News Feed feature to Facebook in 2006, what were some people’s objections to it? Why was it ultimately determined to be widely successful and the cause of the site’s massive growth?

What is “ambient awareness” and how is it similar and different in online and offline interactions?

Summarize the development of the “Dunbar number” (par. 27) and explain its application to online social media. According to the article, has social media expanded the Dunbar number?

What are some of the benefits and detriments of the “weak ties” that are often created and developed through social media?

What does media researcher Danah Boyd mean about some online relationships when she says, “They can observe you, but it’s not the same as knowing you” (par. 33)?

Look back at the following passage from paragraph 39. What does it reveal about the complexity of online relationships?

For them, participation isn’t optional. If you don’t dive in, other people will define who you are. So you constantly stream your pictures, your thoughts, your relationship status and what you’re doing—

right now! — if only to ensure the virtual version of you is accurate, or at least the one you want to present to the world. Page 800What evidence does sociologist Zeynep Tufekci offer to support her claim that social media is taking us back to a “normal place, historically” (par. 41) in our social relations, similar to what existed before the twentieth century?

In the last two paragraphs, Thompson explains one more benefit some users of social media have identified: the ability to “know thyself.” According to Thompson, why is this a desirable outcome and how can social media help with this?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What does the following section from paragraph 12 reveal about the author’s initial tone toward social media?

The growth of ambient intimacy can seem like modern narcissism taken to a new, supermetabolic extreme—

the ultimate expression of a generation of celebrity- addled youths who believe their every utterance is fascinating and ought to be shared with the world. Twitter, in particular, has been the subject of nearly relentless scorn since it went online. “Who really cares what I am doing, every hour of the day?” wondered Alex Beam, a Boston Globe columnist, in an essay about Twitter last month. “Even I don’t care.” After using primarily an objective, third person point of view, Thompson actively inserts himself into the story, describing his first steps using Twitter (par. 21). Look back through the piece to identify other places where he writes about himself and explain what is gained in his argument about social media by his own personal anecdotes.

In addition to interviewing experts on the topic of social media, the author includes information about three social media users. Look back at each, and explain how each contributes a different aspect to the argument:

Ben Haley (pars. 13–

17) Shannon Seery (pars. 21–

24) Andrea Ahan (pars. 35–

39)

What does the author’s word choice in the following sentence from paragraph 44 suggest about his attitude toward social media’s demands on its users? “They curate their online personas as carefully as possible, knowing that everyone is watching.”

Skim back through and identify where Thompson describes positive aspects of social media and where he describes negative ones. Overall, on which side does he land? What words and phrases reveal his position most clearly?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

In paragraph 43, this article references the famous 1993 New Yorker cartoon about anonymity online. You can see the cartoon in the chapter introduction on page 666. Is the conclusion—

the Internet allows for total anonymity— still valid today? Why or why not? In what ways is Zeynep Tufekci, the sociologist Thompson quotes in paragraph 41, correct when she claims that the new social media technology actually makes our relationships more like they might have been in the past? Explain your reasoning with research you conduct or interviews with people who grew up pre-

Internet. Define friend in the era of social media. What are the different roles that online and offline friends play in your own life, and what are the similarities and differences in the ways that you communicate with them?