9.19

from Alone Together

Sherry Turkle

Sherry Turkle (b. 1948) is a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the director of its Initiative of Technology and Self, which aims to study the ways that the new technologies “raise fundamental questions about selfhood, identity, community, and what it means to be human.” Turkle has published several texts on the ways that we interact with various electronic devices and with each other on social media sites. Some of her works include The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit; Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet; and The Inner History of Devices.

KEY CONTEXT This excerpt is taken from Turkle’s book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, which was published in 2011. Turkle is a licensed clinical psychologist, and a significant part of her background and training is in psychology. She gathers much of her data through interviews and focus groups with her subjects, who, in this excerpt, are mostly teenagers. Turkle asks them regularly about their feelings, as a therapist might. Much of the evidence that she uses to support her arguments about the ways that teenagers interact with social media comes in the form of transcripts of these interviews.

Roman, eighteen, admits that he texts while driving and he is not going to stop. “I know I should, but it’s not going to happen. If I get a Facebook message or something posted on my wall . . . I have to see it. I have to.” I am speaking with him and ten of his senior classmates at the Cranston School, a private urban coeducational high school in Connecticut. His friends admonish him, but then several admit to the same behavior. Why do they text while driving? Their reasons are not reasons; they simply express a need to connect. “I interrupt a call even if the new call says ‘unknown’ as an identifier — I just have to know who it is. So I’ll cut off a friend for an ‘unknown,’” says Maury. “I need to know who wanted to connect. . . . And if I hear my phone, I have to answer it. I don’t have a choice. I have to know who it is, what they are calling for.” Marilyn adds, “I keep the sound on when I drive. When a text comes in, I have to look. No matter what. Fortunately, my phone shows me the text as a pop up right up front . . . so I don’t have to do too much looking while I’m driving.” These young people live in a state of waiting for connection. And they are willing to take risks, to put themselves on the line. Several admit that tethered to their phones, they get into accidents when walking. One chipped a front tooth. Another shows a recent bruise on his arm. “I went right into the handle of the refrigerator.”

I ask the group a question: “When was the last time you felt that you didn’t want to be interrupted?” I expect to hear many stories. There are none. Silence. “I’m waiting to be interrupted right now,” one says. For him, what I would term “interruption” is the beginning of a connection.

Today’s young people have grown up with robot pets and on the network in a fully tethered life. In their views of robots, they are pioneers, the first generation that does not necessarily take simulation to be second best. As for online life, they see its power — they are, after all risking their lives to check their messages — but they also view it as one might the weather: to be taken for granted, enjoyed, and sometimes endured. They’ve gotten used to this weather but there are signs of weather fatigue. There are so many performances; it takes energy to keep things up; and it takes time, a lot of time. “Sometimes you don’t have time for your friends except if they’re online,” is a common complaint. And then there are the compulsions of the networked life — the ones that lead to dangerous driving and chipped teeth.

Today’s adolescents have no less need than those of previous generations to learn empathic skills, to think about their values and identity, and to manage and express feelings. They need time to discover themselves, time to think. But technology, put in the service of always-

5 I wonder about this as I watch cell phones passed around high school cafeterias. Photos and messages are being shared and compared. I cannot help but identify with the people who sent the messages to these wandering phones. Do they all assume that their words and photographs are on public display? Perhaps. Traditionally, the development of intimacy required privacy. Intimacy without privacy re-

Several boys refer to the “mistake” of having taught their parents how to text and send instant messages (IMs), which they now equate with letting the genie out of the bottle. For one, “I made the mistake of teaching my parents how to text-

Teenagers argue that they should be allowed time when they are not “on call.” Parents say that they, too, feel trapped. For if you know your child is carrying a cell phone, it is frightening to call or text and get no response. “I didn’t ask for this new worry,” says the mother of two high school girls. Another, a mother of three teenagers, “tries not to call them if it’s not important.” But if she calls and gets no response, she panics:

I’ve sent a text. Nothing back. And I know they have their phones. Intellectually, I know there is little reason to worry. But there is something about this unanswered text. Sometimes, it made me a bit nutty. One time, I kept sending texts, over and over. I envy my mother. We left for school in the morning. We came home. She worked. She came back, say at six. She didn’t worry. I end up imploring my children to answer my every message. Not because I feel I have a right to their instant response. Just out of compassion.

Adolescent autonomy is not just about separation from parents. Adolescents also need to separate from each other. They experience their friendships as both sustaining and constraining. Connectivity brings complications. Online life provides plenty of room for individual experimentation, but it can be hard to escape from new group demands. It is common for friends to expect that their friends will stay available — a technology-

Traditional views of adolescent development take autonomy and strong personal boundaries as reliable signs of a successfully maturing self. In this view of development, we work toward an independent self capable of having a feeling, considering it, and deciding whether to share it. Sharing a feeling is a deliberate act, a movement toward intimacy. This description was always a fiction in several ways. For one thing, the “gold standard” of autonomy validated a style that was culturally “male.” Women (and indeed, many men) have an emotional style that defines itself not by boundaries but through relationships.1 Furthermore, adolescent conversations are by nature exploratory, and this in healthy ways. Just as some writers learn what they think by looking at what they write, the years of identity formation can be a time of learning what you think by hearing what you say to others. But given these caveats, when we think about maturation, the notion of a bounded self has its virtues, if only as a metaphor. It suggests, sensibly, that before we forge successful life partnerships, it is helpful to have a sense of who we are.2

10 But the gold standard tarnishes if a phone is always in hand. You touch a screen and reach someone presumed ready to respond, someone who also has a phone in hand. Now, technology makes it easy to express emotions while they are being formed. It supports an emotional style in which feelings are not fully experienced until they are communicated. Put otherwise, there is every opportunity to form a thought by sending out for comments.

The Collaborative Self

Julia, sixteen, a sophomore at Branscomb, an urban public high school in New Jersey, turns texting into a kind of polling. Julia has an outgoing and warm presence, with smiling, always-

If I’m upset, right as I feel upset, I text a couple of my friends . . . just because I know that they’ll be there and they can comfort me. If something exciting happens, I know that they’ll be there to be excited with me, and stuff like that. So I definitely feel emotions when I’m texting, as I’m texting. . . . Even before I get upset and I know that I have that feeling that I’m gonna start crying, yeah, I’ll pull up my friend . . . uh, my phone . . . and say like . . . I’ll tell them what I’m feeling, and, like, I need to talk to them, or see them.

Reflect on your own cell phone usage. How often have you checked it today? Or even this class period? Are you checking it right now?

“I’ll pull up my friend . . . uh, my phone.” Julia’s language slips tellingly. When Julia thinks about strong feelings, her thoughts go both to her phone and her friends. She mixes together “pulling up” a friend’s name on her phone and “pulling out” her phone, but she does not really correct herself so much as imply that the phone is her friend and that friends take on identities through her phone.

After Julia sends out a text, she is uncomfortable until she gets one back: “I am always looking for a text that says, ‘Oh, I’m sorry’, or ‘Oh, that’s great.’” Without this feedback, she says, “It’s hard to calm down.” Julia describes how painful it is to text about “feelings” and get no response: “I get mad. Even if I e-

Claudia, seventeen, a junior at Cranston, describes a similar progression. “I start to have some happy feelings as soon as I start to text.” As with Julia, things move from “I have a feeling, I want to make a call” to “I want to have a feeling, I need to make a call,” or in her case, send a text. What is not being cultivated here is the ability to be alone and reflect on one’s emotions in private. On the contrary, teenagers report discomfort when they are without their cell phones.4 They need to be connected in order to feel like themselves. Put in a more positive way, both Claudia and Julia share feelings as part of discovering them. They cultivate a collaborative self.

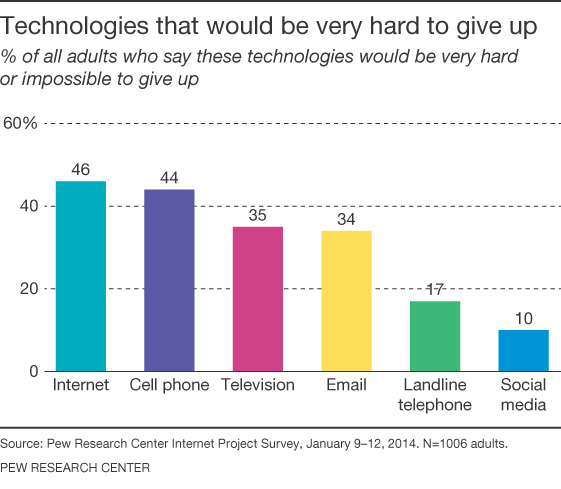

What would you predict would be the results for teenagers? Why? Which technologies would be the hardest for you to give up?

15 Estranged from her father, Julia has lost her close attachments to his relatives and was traumatized by being unable to reach her mother during the day of the September 11 attacks on the Twin Towers. Her story illustrates how digital connectivity — particularly texting — can be used to manage specific anxieties about loss and separation. But what Julia does — her continual texting, her way of feeling her feelings only as she shares them — is not unusual. The particularities of every individual case express personal history, but Julia’s individual “symptom” comes close to being a generational style.5

Sociologist David Riesman, writing in the mid-

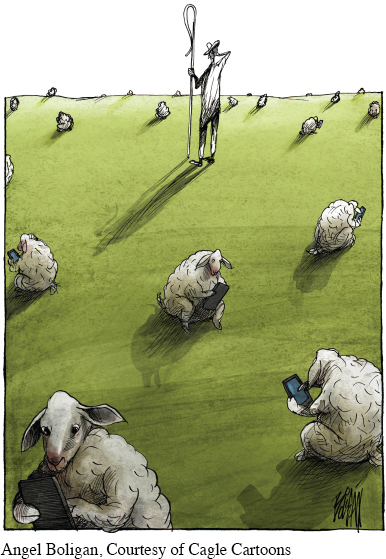

What point is the cartoonist trying to make and what analogy is he relying on to make it? Is it effective in making the point?

Ricki, fifteen, a freshman at Richelieu, a private high school for girls in New York City, describes that necessity: “I have a lot of people on my contact list. If one friend doesn’t ‘get it,’ I call another.” This marks a turn to a hyper-

Again, technology, on its own, does not cause this new way of relating to our emotions and other people. But it does make it easy. Over time, a new style of being with each other becomes socially sanctioned. In every era, certain ways of relating come to feel natural. In our time, if we can be continually in touch, needing to be continually in touch does not seem a problem or a pathology but an accommodation to what technology affords. It becomes the norm.

Understanding and Interpreting

What does the author conclude about how and why teenagers interpret interruptions differently than adults do?

Reread the fourth and fifth paragraphs. Write a statement or two that captures Turkle’s thesis. In other words, what is she hoping to communicate to her readers in this selection?

Turkle claims in paragraph 8 that “[c]onnectivity brings complications.” What complications does she identify and what evidence does she include to support her claim?

Turkle states, “Traditional views of adolescent development take autonomy and strong personal boundaries as reliable signs of a successfully maturing self” (par. 9). According to Turkle, how does today’s connected world make this development more difficult?

Write a definition of “the collaborative self” (see the heading following par. 10). What would Turkle likely say is wrong with the idea of a collaborative self?

Though she never directly says in this excerpt, what can you infer about possible solutions Turkle might suggest to the problem she sees in today’s connected world?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What does Turkle achieve by starting with quotes from teenagers who admit to texting while driving?

While the focus of this piece is on teenagers’ use of technology for communication, Turkle includes a long quote from a mother who texts her children (par. 7). How does this passage support Turkle’s main point on adolescent development?

While Turkle’s style could probably be described as that of a dispassionate researcher who is simply recounting the evidence she has collected, there are moments throughout this piece where Turkle seems to step away from that approach, describing her subjects with a more personal eye. Identify one or more of these places and explain how her choice helps to support her purpose for writing this piece.

Overall, is Turkle’s argument convincing? How does she establish her own ethos and utilize both logos and pathos to support her position?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Turkle quotes a number of teenagers throughout this piece. Skim back through and identify one interviewee who either shares your views on social networking or holds a very different viewpoint. Then, compare and contrast your attitude toward this technology’s impact on your life and relationships with the attitude expressed by the interviewee.

Write an analysis of how you use social media for communication and how your online social relationships compare to your offline relationships. To help you write this analysis, you may choose one of the following activities or develop your own:

Page 807Chart your online and offline interactions with friends and family for a period of time (at least one day, no longer than a week). Create a graph that compares the time that you spend connecting with others online, offline, or both, and write an analysis.

If you are an active user of social media, identify a twenty-

four- hour period when you will try not to use any social media. If you are not a heavy social media user, identify a twenty- four- hour period in which you will try to do the majority of your communicating with friends through social media. After your experiment, explain what differences you noticed in the ways that you communicate. Look back through your texts, status updates, tweets, and recent pictures and postings from your regular social media sites. Explain the different ways that you communicate based upon the medium you use.

Overall, is the constant communication that technology enables a positive or a negative force in society? Support your argument with references to the Turkle selection as well as with your own research and interviews with family and friends.

The National Council of Teachers of English says that literacy in the twenty-

first century must include the ability to “design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes.” How do the digital communications technologies available today allow people from different countries to connect and understand each other? Does this technology facilitate communication in ways that were not previously possible? Research organizations that try to bring people of different cultures together through technology and explain the impact that opportunities for global information sharing might have in the future.